Monkeypox: What are the dangers of zoonotic diseases?

As ‘monkeypox’ hits the headlines this week, many are wondering if it risks becoming the new COVID-19.

So far 92 cases have been identified in countries where the disease is not endemic. Symptoms include fever, fatigue and a blistering rash for those who contract the virus.

Positive cases have been found in Australia, Canada and the USA, with European countries Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden and the Netherlands all reporting cases.

Spain and Portugal, as of Sunday, all had between 21-30 cases each.

However, the highest numbers are in the UK.

Previous outbreaks in the UK and Israel were linked to travel to Central and West Africa where the disease is endemic. But person-to-person transmission in Europe seems to be happening now on a larger scale than before.

Monkeypox is generally mild and no fatalities have yet been recorded among the positive cases in Europe, North America or Australia - meaning it poses much less of a threat than COVID-19.

Likewise, a World Health Organisation (WHO) expert has pointed out the spread of monkeypox is different to COVID-19 and easier to contain.

But where the two have some similarities is that they are both zoonotic diseases, which pass from animals to humans.

What are zoonotic diseases?

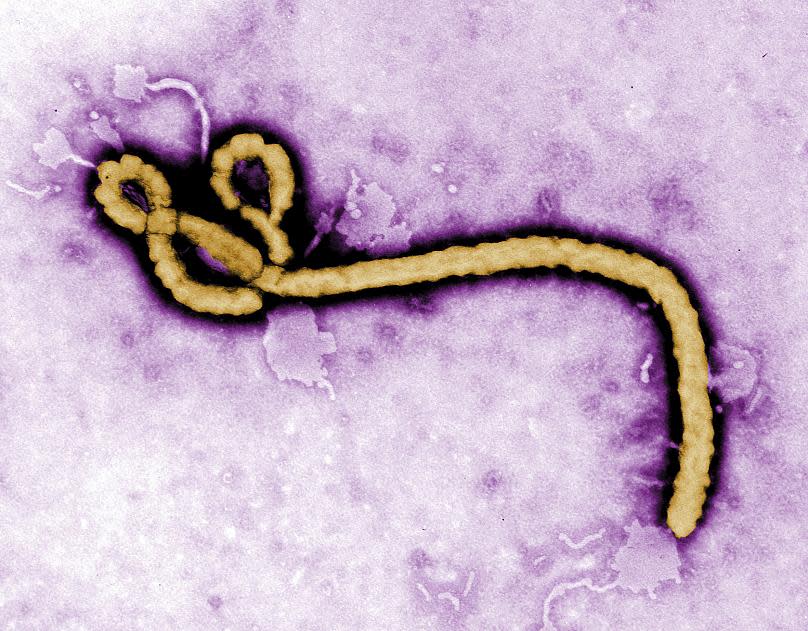

COVID-19 is thought to have spread from a bat which was kept in a wet market in China. Other zoonotic diseases which have spread from animals to humans include HIV/AIDS, anthrax and Ebola.

Monkeypox was first discovered in monkeys in 1958 and the first recorded human case was in 1970.

In African countries where the disease is more common, evidence of the monkeypox virus has been found in many animals including rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice, and many species of monkeys.

“People living in or near forested areas may have indirect or low-level exposure to infected animals,” explains Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, founder and CEO of Conservation through Public Health.

Contagion from animals to humans can be caused through a bite or scratch, with the most likely carriers being rodents.

Other zoonotic diseases can be transmitted through inadequately prepared meat and animal products; this is how anthrax was originally spread.

With monkeypox, the current human-to-human transmission in non-endemic countries is happening through close contact between people.

“With high human population densities particularly in urban areas monkey pox can spread more easily among people and to different continents through air travel,” adds Kalema-Zikusoka.

What are the dangers of zoonotic diseases?

While illnesses like COVID-19 and Ebola pose more of a threat to life than monkeypox, zoonotic diseases do pose particular challenges for human populations.

During the pandemic we’ve seen in real time what happens when a new pathogen begins to infect populations with no immunity, combined with the stress of finding treatments and vaccines.

“They can be difficult to treat if they are not common and not all of them have a direct cure,” says Kalema-Zikusoka.

“For example the treatment for Human Tuberculosis is not the same as the treatment for Bovine Tuberculosis that people get from eating meat or drinking milk from infected cows and buffalo.”

It has taken many decades to develop the highly effective treatment for HIV/AIDS that is used now, with still no effective vaccine available.

It’s the novelty of zoonotic diseases in humans that makes them so dangerous.

How can we prevent zoonotic diseases?

Education is one way to prevent zoonotic diseases, with many ignorant of how they spread.

For example, teaching people the dangers of eating meat from an animal that died of unknown causes, or eating meat that isn’t properly cooked, can stop contagion. Likewise strengthening education on conservation and the need to adhere to the great ape viewing guidelines (mask wearing, 10m distance and a 1hr viewing limit) in the tourism sector can limit the spread.

Legal enforcement of poaching laws would reduce human-animal contact, as would ending deforestation and human intrusion into other wild habitats like swamps.

Above all, a combined approach to human, animal and environmental health can help, says Kalema-Zikusoka, who calls this a ‘One Health’ approach.

“Activities that mitigate and adapt to climate change can help reduce emerging infectious and zoonotic diseases,” she concludes.