Mind your Beeswax: How Sir James Dyson plans to re-invent British farming

On an optimistically bright morning in rural Lincolnshire, Sir James Dyson surveys his kingdom and smiles. ‘Isn’t it all beautiful?’ he asks nobody in particular, shielding his eyes from the sun and studying an endless flat vista of fields and hedgerows. ‘I think it is, anyway…’

We are standing in a gravel car park beside a single-storey office complex. Everything is neat and tidy – unnervingly so, in fact – but there is not a vacuum cleaner in sight. Nor are there any 10-second hand dryers. Or bladeless fans. Or prototype electric cars, for that matter. In short, we are a world away from any of the nifty inventions the 70-year-old is celebrated for, which have made him a Knight Bachelor, a member of the Order of Merit and a billionaire 7.8 times over.

No, Dyson the boffin has been left behind at HQ in Malmesbury, Wiltshire. Instead, he is here today in his rarely spoken-of role as a farmer. Or to be more precise, his rarely spoken-of role as the most powerful farmer in the UK.

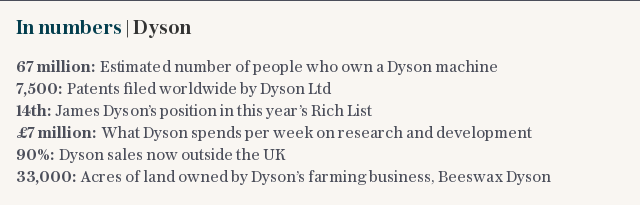

Through Beeswax Dyson Farming Ltd – a separate entity from the eponymous manufacturing firm, to which he dedicates almost all his time – Dyson has spent the better part of a decade quietly purchasing 33,000 acres of prime agricultural land in Lincolnshire, Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, becoming the owner of the largest farming business in the country and a greater private landowner than the Queen.

Until recently, it was not a side of his portfolio Dyson had spoken publicly about, or even attached his name to (the company used to be known simply as Beeswax Farming). Now, though, at what he declares is ‘a potential crisis point for British farming’ post-Brexit, he has decided it’s time to show off a little.

‘It’s true, people don’t know about me and all this, and for a while we did want to keep it separate from the manufacturing business,’ he says, clambering into one of a fleet of spotless Land Rovers on the company’s flagship Carrington estate, a 15-minute drive from Lincoln.

‘I suppose, rather like manufacturing, farming happens in relative secret to the public, so people haven’t really noticed. There should be a lot more interest in it, in my view. It would help in these troubled times...’

Satisfying as it must have been to revolutionise industrial design seemingly at will over the past 40 years, buying farms had, in fact, been an ambition of Dyson’s long before engineering took a hold. As a boy growing up in north Norfolk in the 1950s, he spent much of his childhood outdoors, getting his hands dirty in fields, and kept hold of a desire to some day have his own workable plots.

‘My earliest memories are of digging potatoes, top and tailing Brussels sprouts and picking blackcurrants from the hedgerows. I’d rush parsley to the Campbell’s soup factory in King’s Lynn – it had to be there within an hour for it to be fresh,’ he says.

‘Working on farms and seeing what farms do is a very visceral form of manufacturing. It’s growing and happening in front of you. I missed that, in a way, and about 10 years ago I was fortunate enough to have the money to buy farms and become a very part-time farmer myself. I’d have liked to buy in Norfolk and complete the thing, but this is Grade 2 [meaning ‘very good quality’] Lincolnshire farmland – you can’t get much better.’

The name Beeswax was the idea of Deirdre, Dyson’s wife of 49 years, and inspired by the apiaries they own on the Dodington Park estate, their home in Gloucestershire. The family connection runs through everything: even the company’s crest features personal references to Deirdre and the children. He talks me through its features.

‘My wife likes to paint, so there’s a palette for her. Then there’s a guitar for my son Sam [who was in a rock band, The Chemists], a T-shirt for my daughter, Emily, who is a fashion designer, and two micrometers for my eldest son, Jake, and me, because we’re both engineers.’

Agriculture is such a passion project of Dyson’s that you half expect Carrington to be a full-scale reconstruction of his rose-tinted childhood memories, like a muddy, Brexit-y Neverland Ranch. In reality, it takes just a morning touring the site to realise he is both deadly serious about farming and entirely uninterested in looking back. With him as a guide, it is more like glimpsing the utopian, sustainable future of large-scale farming. And it’s very impressive.

‘Farms these days have become as efficient as they can possibly get,’ he tells me, as we glide down to a clutch of huge barns. ‘There’s not a lot more we could do to streamline things here, as you’ll discover, but we’re always trying…’ Land purchases aside, Dyson has ploughed £75 million of his own fortune into Beeswax Dyson, and though this year turnover was £14.1 million and losses have shrunk from £4.5 million to £600,000, profit remains elusive.

Until big changes are made, and farmers a better price for their goods, there will need to be support from government

Sir James Dyson

It’s productive, though. The latest harvest brought 31,500 tons of wheat, 11,000 tons of spring barley, 9,500 tons of potatoes, 4,300 tons of vining peas (if you’ve bought frozen peas from Waitrose lately, they were probably grown here) and 105,300 tons of ‘energy crops’ grown for biofuels. Some is exported; some goes straight to UK retailers. As has always been the way with Dyson, middlemen are avoided like muggers.

It doesn’t appear as if he’s going to drive unemployment rates down. Aside from the drivers of a few shiny black-and-grey Beeswax Dyson lorries rumbling past with peas in – the first with the number plate B53 WAX, the second with B54 WAX, and so on – and a few members of the senior management team who accompany us, the place is quite eerily quiet. Beeswax Dyson employs 94 people directly and 500 indirectly, but they must have been tidied away for lunch.

Those we do see are generally supervising or controlling robots doing the hard work for them. It becomes clear that of the £75 million cash injection, quite a lot has been spent on farming technology. Self-driving tractors, sprayers and combine harvesters are used as much as possible, often informed by the work of drones.

In one field we meet a drone pilot who flies the remote-controlled helicopters over land all day in order to gather data on which patches are performing best, or requiring the most help. The results are then put into the self-driving tractors and sprayers, which can treat every few square yards differently. The drone cameras will also identify bird nests, such as those of the rare marsh harrier.

‘Just walking through the field, you’d never be able to see those nests; they’re fairly well disguised,’ Beeswax Dyson’s managing director, Richard Williamson, says. ‘When the drone spots them we can block off that section on the computer, and the tractor or combine will move around it.’ It’s one of numerous commitments the company has made to protecting the environment, particularly its wildlife.

EU subsidies – of which Dyson is the biggest recipient in the country – insist on a certain level of reinvestment in the environment, but the Beeswax estates go far beyond what is required. Dyson has repeatedly turned down offers relating to wind turbines or solar farms, both of which could have made him billions. (He hates the look of wind turbines, and thinks the science is inefficient: this is a man who made a bladeless fan, so he doesn’t approve of turbine-generated energy.)

Instead, aside from the installation of new, responsible drainage systems on all the company’s land (to the tune of £5 million), the management of 93 miles of hedgerows and 47,840sq yd of fallow land has seen wild flora and fauna flourish on quiet, peaceful farmland.

There are also more than 100 disguised boxes for small birds, as well around the same number of owl boxes, a few protected lapwing nests and various roomy structures for young kestrel families to get on the ladder. Winged creatures are a theme. Staff are working with a local bat group to discover what they can do for those, and last year a rare mining bee was spotted nearby for the first time in a century.

‘There’s the bee connection again,’ Dyson says, chortling. ‘We do far, far more than we need to, and we’re fortunate to be able to afford that, of course. But treading lightly – you know, impacting the ground as little as possible in your farming – is so important, both in being sustainable and just from a business point of view. If you harm the ground you will not be as productive – that is quite obvious.’

It would be a profound understatement to say that Dyson does not look like a farmer. Today he is a vision in softly layered blues, including blue suede desert boots, and occasionally he adds a pair of thick, round-framed glasses to finish things off. He is tall and rangy, with alarmingly long legs and cloud-white hair. It’s a look that once made him appear like an excitable geography teacher; now he looks like a hipster BFG.

Fortunately, he doesn’t pretend to roll up his sleeves and till the soil every spare weekend. He has plenty to get on with at Dyson’s headquarters in Wiltshire, not least the ‘radically different’ electric car he has been working on since 2015 but only announced in September, and the on-site university he set up for young engineers last year. Instead, his farming vision is enacted by a crack team of experts, led by Williamson in Lincolnshire.

I do not see leaving the European Union as a disaster at all. It’s a very minor blip if you’re exporting to Europe; that’s it

Sir James Dyson

Dyson’s fingerprints are everywhere, mind. We pause at a vast anaerobic digester (AD), which runs on cheap energy crops and waste food such as onions, turning them into renewable energy to power 10,000 homes. Any leftover heat is used to dry grain and woodchip, lowering both costs and the farm’s future carbon footprint. And as if that wasn’t enough, leftover digestate from the whole process goes back on the fields as a natural fertiliser.

It is clever-dickery on a grand scale, and pure Dyson. With ear defenders on, we stand and look at the AD humming for a while. He beams, and points at things to mime an explanation of how it all works. Don’t be surprised if the Dyson company’s tally of 7,500 patents grows to include a heap of farm tech in the future. Back in the quiet of the office, he considers his entry into an industry fraught with uncertainty, not least in relation to Europe.

‘It’s an unusual time to get into farming, I will admit that, but we started purchasing land long before Brexit was a possibility,’ he says. ‘I do not see leaving the European Union as a disaster at all. It’s a very minor blip if you’re exporting to Europe; that’s it. It’s actually a disaster for Europe, because it’ll cost them a lot more to export to us…’

As one of the few business leaders who came out in favour of Brexit, Dyson is asked about it everywhere he goes, and generally parries criticisms like the dedicated weekend tennis player he is.

He enjoys the spirited debate. Earlier, walking around, he twice joked, ‘We’ll have to ask the EU first!’ when discussing something entirely trivial, such as opening a gate. Later, when he crouches in a field for a photo and feels a sharp scratch, he will pick out the offending weed and shout, ‘Oh God, look, an EU thistle!’ The staff will chuckle, and we get it: he voted to leave. ‘I don’t think they’ll do a deal,’ he says of David Davis’s chances around the negotiating table.

‘You can’t negotiate with that lot, as I’ve found out from 24 years of sitting on European committees with Dyson. No non-German company has ever won anything, and nobody has ever been able to block any suggestion from the German cartel. Never. They stifle innovation, the EU. And the European Court of Justice, well, that’s frankly crooked…’

Still, the EU does give Beeswax Dyson £1.6 million a year in subsidies, which is a figure he will happily admit to taking, but says turns to peanuts once you’ve followed the demands Brussels makes of farmers. He also believe subsidies will be essential post-Brexit.

‘You can see the efficiency, going around here today. We have big financial backing and we are as efficient as is possible in farming, but it is still difficult to make money when the deal that British farmers get from supermarkets is so outrageous,’ he says. ‘Until big changes are made to the structure of those deals, cutting out the middlemen and getting farmers a better price for their peas or milk or whatever it is, there will need to be support from government.’

There is a stubborn, warrior mentality to Dyson’s attitude, almost as if he’s entered agriculture purely to give himself the greatest challenge possible on the Brexit front line. He does, after all, have enough on his plate attempting to save the motoring industry now – plus all the other sectors he could be working on in secret. At a decade old, though, it is early days for Beeswax Dyson, and it doesn’t seem a selfish exercise.

The generous but financially pointless deeds I am shown are endless: renovating original cottages on the land, at vast expense, for staff and their young families to live in; replacing the local cricket pavilion and football pitch for a token £1; investing £2 million to restore 10 miles of historic stone walling with local stone…

‘We take a very, very long-term view here: 100 years or so – that’s the length of time we work on, and that explains some of the practices, I hope. We’re happy with the land we’ve got, but we can try and get more ambitious and better at how we do things, maintaining that focus on sustainability,’ he says. ‘You don’t know what will happen, but it’s a multigeneration project in the family, and not just about me. We want it to last.’