Mike McCartney on growing up with Paul: ‘I waited all night to meet Jane Asher’

Mike McCartney still isn’t sure whether he’ll go to Glastonbury next month to watch his older brother Paul headline the Pyramid Stage. The younger McCartney sibling went to the Somerset festival the last time his brother headlined in 2004, and he has one overriding memory. Mud.

“I took my two eldest boys. We just stood there as we were going in. There’s Glastonbury down there and bloody miles of tents. But there, on the top, all the grass has gone. Total mud with footprints,” says the 78-year-old photographer and former musician. They “slid” to go and watch US rockers The Killers play. It doesn’t matter though. Because music inspired by his Beatle brother is happening closer to home this summer. Much closer. The McCartney’s childhood home at 20 Forthlin Road in Liverpool is being opened up to musicians for the first time.

‘The Forthlin Sessions’ will see four unsigned artists visit, write and perform in the tiny former council house’s front room, in the very space where Paul and John Lennon wrote early Beatles songs including Love Me Do. The scheme is being run by the National Trust, which has looked after the property since 1992 having restored it to its Fifties and Sixties iteration. The idea behind the Sessions, though, is that Forthlin Road inspires a new generation of songwriters rather than exists as a mere shrine to The Beatles.

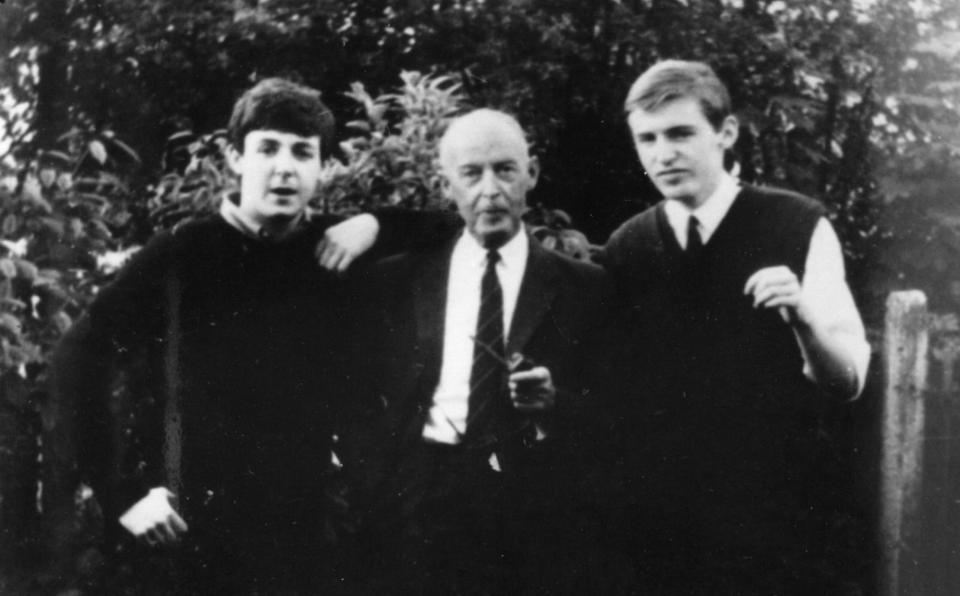

I’m talking to Mike in the house’s front room, complete with its brown Bakelite television, old upright piano and vintage wallpaper. The walls are hung with his location-specific photographs of his brother at work, either alone or with Lennon: so above the corner by the fire where the pair wrote I Saw Her Standing There is a photo of them hunched over their guitars as they worked on that song. The sense of musical history is palpable. As we chat, the young musicians who’ve been picked for the Sessions pad around the house seeking creative osmosis from its rooms (we’re at the ‘visit’ stage of the process – the artists will return to perform their songs on 17 June, the day before Paul’s 80th birthday).

Although the house has 12,000 visitors a year, Mike is aware that this is special. “It’s going to be fascinating hearing music again for the first time. I have never heard music in here since we lived here. That’s got to be nearly 60 years,” says Mike, who’s tall and silver-haired and shares the cheeky glint of his more famous brother. The new music, he says, will “bring [the house] alive”.

What’s heartening is that The Beatles, who broke up in 1970, clearly resonate with the Gen Z musicians present, who were born in the years around the millennium. They’re aware of the house’s history but, thankfully, not over-awed by it. Bath-based contemporary folk duo Humm tell me they already play Dear Prudence in their set. “We grew up with The Beatles,” says Humm’s Arty Jackson, 23. Emily Williams, a 23-year-old who performs under the name Emily Theodora, says that The Beatles have influenced all the bands she loves, such as the White Stripes.

To run alongside the Sessions, a new film and poem called An Ordinary House, An Ordinary Street has been made, featuring a cast of Liverpudlians. It is this ordinariness that the musicians want to tap into. Serena Ittoo, 22, praises McCartney’s self-belief having started from humble beginnings. “I want to do today justice,” she says. Meanwhile singer-songwriter Dullan Ellis, 25, says that song ideas lurk in every room. “Every nook and cranny has a story,” says.

Forthlin Road has huge poignancy for the McCartney brothers. The year after the family moved in in 1955, their mother Mary – a midwife – died of breast cancer, leaving their father Jim to bring them both up on around £10 a week. They remained there until 1964. I ask Mike whether he and Paul – who he calls “Our Kid” – threw themselves into creative pursuits as a way of dealing with their mother’s death. “Both of us lost ourselves in art. Yes we did. You’d have to ask my brother if that was the same for him. But I saw him. He’d just get lost [in music]. He was away,” he says.

The younger sibling, who has the knockabout air of fellow Scouser Ken Dodd about him, goes even further. He says that had their mother lived, their lives could have taken radically different paths. “If my mum had lived, you wouldn’t be talking to jolly, whack-a-wit Mike McCartney. You’d be talking to Dr McCartney or Father McCartney. Because all our lives she wanted us to better ourselves,” he says.

As well as poignant memories, the house holds plenty of amusing ones. Some border on the surreal. Such as the time Mike met Jane Asher in the dead of night in his old bedroom upstairs. Paul dated actress Asher from 1963 until 1968, and early in their relationship brought her up to Liverpool to meet his brother and father.

Mike only knew Asher from watching the show Juke Box Jury on their black and white TV. She was, he thought, “like a posh Brigitte Bardot, blondie, London, lived in Wimpole Street”. The fact she was coming to 20 Forthlin Road was astonishing. The evening of the couple’s arrival, Mike and Jim “waited and waited” but they didn’t show up. So they went to bed.

“I got my pyjamas on, striped old-fashioned pyjamas, and waited some more. I was determined to stay awake. It was Jane Asher, for god’s sake. Eventually, at about two or three in the morning, I could hear the key in the front door. They’re sneaking upstairs,” Mike says. “The next thing I know, there is the blonde goddess from Juke Box Jury coming straight towards me with her hand outstretched, and there’s me in my pyjamas. Except… she has suddenly got bright red hair because on the black and white telly it looked blonde.” What did you say? “I couldn’t say anything. ‘Your hair’s red!’ is not quite the thing to say to a renowned actress.”

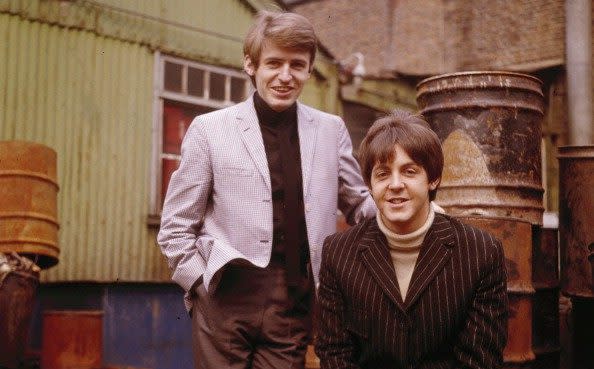

Mike is not unfamiliar with chart success himself. He was a member of comedy trio The Scaffold and then performed as a solo artist under the pseudonym Mike McGear. The Scaffold had a number one hit in 1968 with Lily the Pink having reached the top five the year before with Thank U Very Much (“for the Aintree Iron, thank you very much, thank you very very very much”). Mike says he wrote the latter song when he rang Paul to thank him for sending him a Nikon camera as a birthday present.

“I got on the phone to thank Our Kid. The trick he had then, because of Beatlemania, was that if anybody rang the house down in London he’d pick up the phone and wait for you to speak. Because if you were a fan or The Daily Telegraph then he would become an Indian restaurant or a Chinese takeaway,” Mike explains. “Whilst I was waiting for him to pick up, this little tune popped into my head. And so he picked up – silence – and I said, ‘Thank you very much for the Nikon camera, thank you very much, thank you very very very much.’”

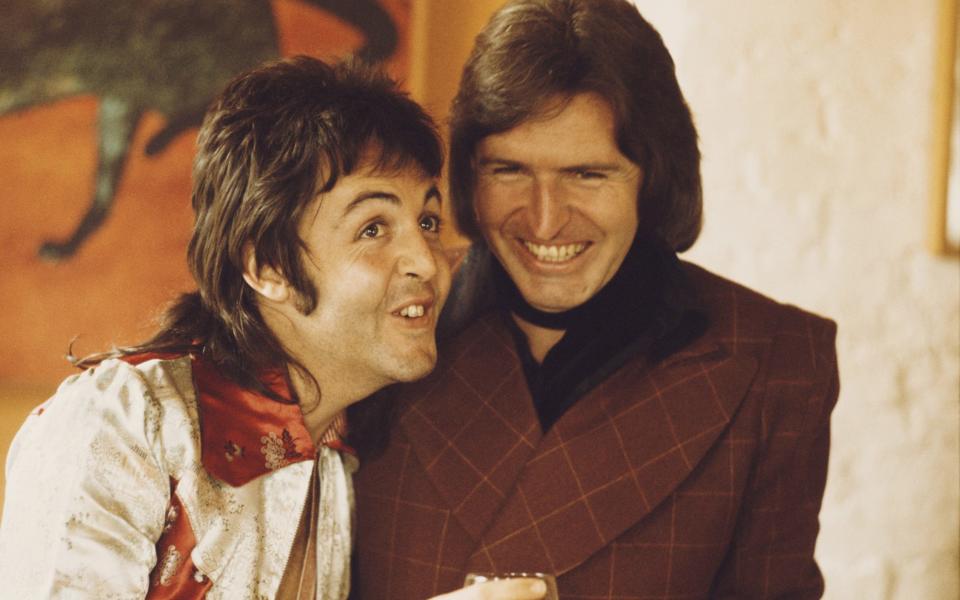

Beatlemania must have been strange. Paul paid for the family to move “over the water” to Heswall on the Wirral in 1964. They had to leave Forthlin Road at midnight to avoid fans. I ask Mike what is it like being the brother of Sir Paul McCartney, arguably the most famous and fêted musician in the world? “Initially, it’s like everyone else with an elder brother. And then your elder brother does rather well for himself, and for us, as the family, it’s nothing but pride and joy.”

He gestures around Forthlin Road’s small front room. “Can you imagine coming from this, which is lots of wonderful memories, and then going to that? And all the things that go with that.” By “all the things” he means the glitzy life of the one per cent, the film premieres and the rubbing shoulders with royalty.

I can’t imagine it, no. Sitting in the small room it’s a contrast – the difference between “this” and “that” – that feels almost unfathomable. Last month, Paul was named in The Sunday Times Rich List as the UK’s wealthiest musician, with a fortune of £865 million (along with his wife Nancy Shevell).

Mike says he’s in touch with his brother “all the time”. A day or so before the interview, Paul sent him a joke photo to his phone. It was a picture of an empty guitar rack that simply said “air guitars” above it.

You get the impression Mike keeps his brother grounded. This becomes clear when I ask him what he’s getting Paul for his 80th birthday. “I’m not bloody telling the Telegraph! It’s called a surprise,” he says. “He should be bloody luck to get anything. He forgot my birthday once. I made it quite clear that he’d forgotten.” A short pause and a smile. “He’s never forgotten again.”