This man isn’t a best-selling author, but he did write his debut novel blind

Joel Burcat’s debut novel, “Drink to Every Beast”, isn’t climbing best-seller lists or getting attention from prominent critics. But it’s remarkable for a different reason.

He finished it after he became legally blind.

An environmental lawyer in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Mr Burcat, 64, had been writing in his spare time for many years and had cranked out several novels, including an early version of this one. But none had found a publisher and gone out into the world.

Then, in early 2018, he lost much of the vision in his right eye to the same affliction that a year and a half earlier had ravaged his left.

To cope with the physical and emotional adjustment, he stepped away from his legal work and realised that he had extra time to write. More than that, he had extra determination.

“I had to prove to myself that I could do something that one would not normally say a blind person can do,” he told me during a recent phone conversation. “It was really, really important to me.”

He got dictation software, hired an editor and then sent a polished revision of “Drink to Every Beast,” a legal thriller about toxic waste in the Susquehanna River, to Headline Books, which welcomes writers unrepresented by agents. It published the novel a few weeks ago.

No matter the book’s reception, he’s beyond ecstatic. “Now,” he said, “I can claim to be in the same category as James Joyce, James Thurber and other blind authors.”

They weren’t totally blind. But Mr Burcat is right about a fascinating tradition of writers with little or no eyesight — fascinating because they affirm human beings’ power to transcend apparent limits, because they show how obstacles can be gateways to epiphanies and because they challenge what it means to see.

For that you use your brain — where images are stored, organised, edited and turned into words — as much as your eyes. You use your spirit.

Within the densest fog and darkest black, you can find clarity and colour if your imagination is 20-20.

That’s the lesson of John Milton, of Jorge Luis Borges and of dozens of less celebrated writers who worked without eyesight, which, in most cases, like theirs, they lost as adults.

They needed assistance, but they pressed on. It steeled them. They responded to a world that often marginalizes or condescends to disabled people by demonstrating just how able they were.

Mr Milton produced “Paradise Lost” and “Paradise Regained” more than a decade after his eyes failed around 1652. “A good argument can be made that he was able to render these masterpieces not in spite of his blindness but because of it,” John Rumrich, who teaches Mr Milton at the University of Texas, told me.

“Language, that most human invention, can enable what, in principle, should not be possible. It can allow all of us, even the congenitally blind, to see with another person’s eyes.”

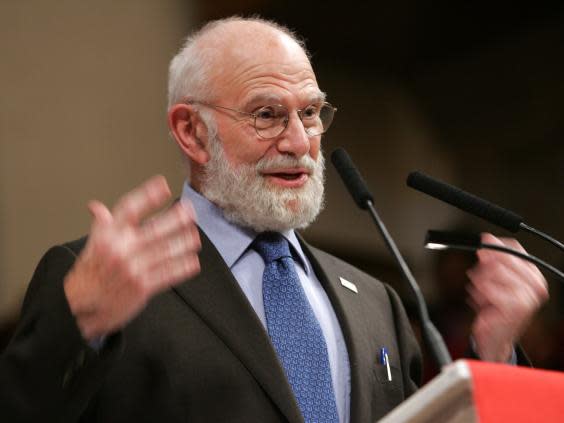

The Mind's Eye by Oliver Sacks

“He himself thought as much.” Mr Milton chose to regard blindness as the price he was paying for “inner illumination,” Mr Rumrich said. It bolstered his sense of mission.

It certainly shaped “Paradise Lost,” which teems with the binaries of day and night, darkness and light, and reflects on his own blindness, which he describes as an all-encompassing blank that has expunged nature’s glory.

Mr Borges, the Argentine fiction writer, poet and essayist, had Mr Milton in mind when he observed in a 1977 essay that “a writer, or any man, must believe that whatever happens to him is an instrument: Everything has been given for an end.

This is even stronger in the case of the artist. Everything that happens, including humiliations, embarrassments, misfortunes, all has been given like clay, like material.” He added that “if a blind man thinks this way, he is saved. Blindness is a gift.”

Mr Borges turned the loss of his eyesight into a gorgeous poem, “On His Blindness,” which notes that he can no longer savour “the closed encyclopedia,” “the tiny soaring birds,” “the moons of gold.” “Others have the world, for better or worse,” it concludes. “I have this half-dark, and the toil of verse.”

I have a special interest in Milton and Borges — and became aware of Burcat — because of my own diminished eyesight. More than a year and a half ago, I woke up with profoundly blurry, clouded vision in my right eye and learned that I’d had a sort of stroke of the optic nerve. The damage was permanent.

What happened to me is technically known as nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, or Naion, which could strike my left eye, too: There’s a roughly 20% chance of that. After I recounted this in a column, Mr Burcat reached out to me. Naion was the culprit in his blindness.

He and I have tools available to us — audiobooks, voice-to-text technology, enormous computer screens on which letters can be supersized — that weren’t around decades, let alone centuries, ago.

But James Wilson, who was blind, nonetheless produced “Biography of the Blind” in the early 1800s. In the early 1900s, Helen Keller, who was deaf as well as blind, wrote autobiographical books and essays.

Homer is often portrayed as blind, though it’s hard to know what to make of that: Scholars haven’t determined whether Homer was one poet or a group of them.

There have been enough blind or seriously visually challenged writers that Heather Tilley, a lecturer at Queen Mary University of London, wrote a book that focused just on those of the Victorian era. It’s titled “Blindness and Writing: From Wordsworth to Gissing.”

When I spoke with her recently, I learned about Frances Browne, an Irish poet and novelist in the 19th century who was blind from early childhood but used what she’d heard of the world for literature that betrayed little if any hint of that.

I learned about a celebrated, widely read 19th century travel writer, James Holman, who made his treks and fashioned his prose after he lost his eyesight.

“Although he relies on the people who are around him to describe things officially to him, there’s also quite a strong sense of smell, of the motion of travelling in a carriage, of how the air feels,” Ms Tilley said. “The writing feels more multisensory.”

Blind writers use their craft to make the photo album from the years before blindness permanent. It lifts intellect above flesh, erasing their impediment. It creates a world in which they can move unencumbered.

I asked Mr Burcat, who not only finished “Beast” but also wrote an entire other novel after he lost his sight, how his disability influenced his writing. He said that blindness sharpened his memory, caused him to dwell longer on physical descriptions and “made me much more patient, more kind, more understanding.”

“I’ve always been sympathetic,” he added. “But now I’m empathetic.”

His words remind and comfort me, as I contemplate my own uncertain future, that writing isn’t an act of stenography. It’s a bid for connection. A search for meaning.

Oliver Sacks said it well in “The Mind’s Eye,” a book inspired by his partial loss of vision: “Language, that most human invention, can enable what, in principle, should not be possible. It can allow all of us, even the congenitally blind, to see with another person’s eyes.”

The New York Times