If ethnic minorities are doing so well in schools, why are we still not excelling in our careers?

As the daughter of Nigerian parents – my father was born in Hammersmith but grew up in Lagos, and my mother is from a large town called Ondo State – I was always told that I’d need “to work twice as hard” as my white counterparts.

It wasn't that my parents wanted to instil insecurity but that, in their experience, black people in Britain are often seen as lazy and incompetent. We have to prove our bosses wrong, according to my father. For her part, my mother – who arrived at Gatwick airport as a 19-year-old with nothing but a navy blue handheld suitcase and £50 note – believes that our skin colour speaks louder than our ability.

It has been hammered into many second-generation ethnic minority children that a good education is key to surviving in a workplace that isn’t always keen to accommodate you. We've been raised to believe that going on to further education – preferably to study law, medicine or engineering – will over qualify you for the world of work.

In some industries, such as medicine and computer science, ethnic minorities do over index and in some cases thrive. But according to recent data from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), even if we are UK born and bred, educational success does not always translate into success in the labour market for those from minority ethnic backgrounds. Or, as the researchers put it, it does not necessarily produce the “typical rewards associated with education”.

Focusing on four minority groups – Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and black Caribbean – and comparing them with the white British majority population, the paper found that on average, the UK adult population of ethnic minorities are more likely to come from deprived backgrounds.

Yet we are still likely to be more highly educated than our majority white peers, with nearly 60 per cent of second-generation Indian and Bangladeshi men and around 50 per cent of Indian, Bangladeshi and Caribbean women having tertiary qualifications, compared to 30 per cent of their white majority counterparts.

Over the last few years, black and ethnic minorities have seen their educational opportunities grow. Inner city schools like Ark Evelyn Grace Academy and The City Academy in Hackney are providing a blueprint for the future of their students. And due to the continued efforts of Oxbridge, more people from under-represented backgrounds are choosing to apply. Since 2016, the number of black and ethnic minority applicants being admitted to Oxford has increased from 15.8 per cent to 23.6 per cent in 2020.

The generosity of UK grime artist Stormzy – who has funded scholarships for black students being admitted to the University of Cambridge – has helped, while the Target Oxbridge programme, created by diversity recruitment specialists Rare, announced in January that it has helped 71 black students earn Oxbridge offers for the 2021-22 academic year.

But it seems a good education is only taking ethnic minorities so far – so what’s going wrong in the workplace?

A recent EY study of over 1,000 young black people across the UK found that “despite having a strong desire to succeed in the workplace, young black people continue to be denied the opportunities [that are] open to others”.

Though 13 per cent believed that their ethnicity does not present any barrier to entry to their chosen profession, 26 per cent admitted that, once they are in the workplace, “their ethnicity represents the main barrier to promotion”.

In 2017, the McGregor-Smith Review considered the issues affecting black and minority ethnic groups in the workplace. It acknowledged that “if BME talent is fully utilised the economy could receive a £24 billion boost”, which represents 1.3 per cent of GDP. It pointed out that “insurmountable barriers'' were vast, with the main obstacle being the lack of connections to the “right people”. For employers and organisations, it was unconscious and conscious bias that was identified as the main barrier. “Stereotypical perceptions, lack of understanding of cultural differences, lack of social or professional networks, and language (nuances and office banter),” were issues across the board.

For some, this means disadvantages can persist across generations. The same could also be said for women or people from working class backgrounds; a research project, led by academics at Queen Mary University of London and the University of York, highlighted accent bias in Britain and a hierarchy based on where people live.

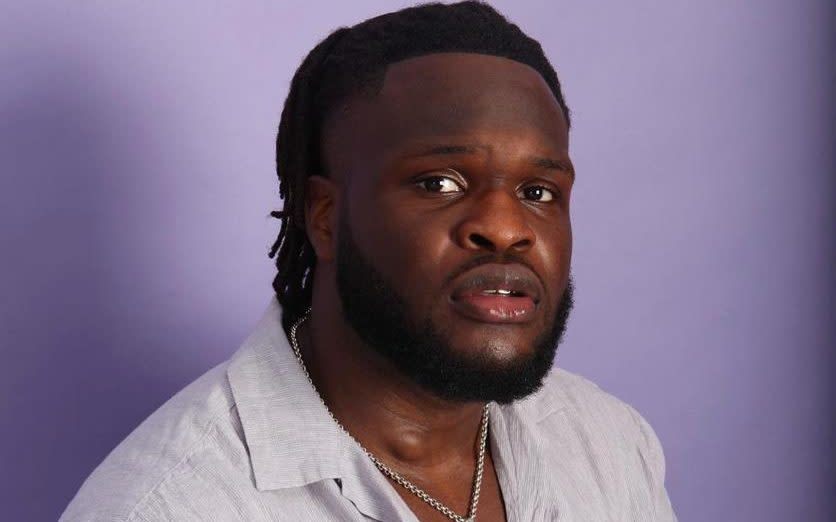

Prince Alayo, from Birmingham, started his “dream job” as a project analyst at Grayce, a graduate talent management consultancy, on April 2. For more than a year, he had been struggling to find employment, despite graduating in 2018 with a first class degree in business management from University College Birmingham and a postgraduate degree in enterprise management in 2020.

“I told my parents that university wasn’t for me, but I knew I didn’t really have a choice,” Alayo says. “I was planning to start my own business, as that’s what I’d seen my father doing. But he told me that as a black person, you need to have an education to be respected by others.”

The 24-year-old says he applied for over 100 roles. “I know so many people who have gone back to university – like I did – to get a masters because they weren’t finding job opportunities in their chosen field.

“I remember when I was finally invited to an interview, and I was confident that it had gone well, but within an hour I was rejected because I was ‘overqualified’. After some time, job hunting can make you feel very inadequate and that [going to] university is a scam.”

Raphael Sofoluke, founder of the UK Black Business Show, points out that there are other hidden barriers to entry for second generation ethnic minorities, even before the interview stage.

“There are studies that show people with African and black-sounding names tend to get fewer callbacks,” the 31-year-old from Bromley says. “So a former colleague of mine put this to the test, and changed her name from Tolu to Tallulah on job applications, and heard back from exactly the same companies she had already applied for. Maybe it was just a coincidence, but this is why a number of recruitment companies are looking to strip names from CVs and go blind.”

When his wife Opeyemi Sofoluke, 29, lead regional diversity and inclusion programme manager at Facebook, started her career, the pressure of having to work twice as hard was always there.

“You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression,” she says. “So if you are being interviewed by people who already have biased or stereotypical views about black people, then you're already at a disadvantage. It’s about having equitable interview processes and diverse teams.”

In their new book, Twice As Hard: Navigating Black Stereotypes and Creating Space for Success, the couple write about the challenges they have faced in their careers. They also speak to over 40 successful business professionals from various industries – including Beyonce’s father Matthew Knowles, Charlene White, the ITV News and Loose Women presenter, and BBC DJ Trevor Nelson – about black identity in the workplace and the practical measures they took to achieve their goals.

“It’s important to be very intentional about your career and set out clear goals,” says Raphael. “It’s easy for black professionals to stay at the bottom of the food chain. So use all the resources around you, whether that is networking or seeking mentorship.

“Why would you not want a mentor? Someone who has experienced all the microaggressions? The imposter syndrome? The code switching [the practice of alternating between languages, dialects or even personalities to fit in]? It's someone who's in the professional world that can teach you how to actually navigate those spaces.”

Opeyemi recommends using platforms like LinkedIn to build a personal brand and be visible. Especially for those who feel like they’ve hit a brick wall with job applications.

Before Nathaniel Opedo went to Durham University to study a degree in sports science and physical activity, his parents wanted to give him a head start, sending him to the independent Whitgift School in South Croydon. For years, his parents sacrificed their time and money (and still do for his two youngest siblings) to ensure that they could pay the school fees and invest into the future of their children.

Now 26, and working as a IT tech recruitment consultant and co-founder of SSensational Sounds, a music collective, he says: “I can see how my education has propelled me through doors, allowed me to pursue professional rugby, and connect with people who are gifted and from wealthy backgrounds. I’ve been told by interviewers that I was invited in because of where I studied.”

As for me? At 26, I’m doing the job I dreamed about, when only 0.2 per cent of British journalists are black. My parents never fail to remind me that I’m “so blessed” to be one of the “lucky ones”.

‘Why did I bother getting a degree if no one wants to employ me’

Marthina Amarachi, 21, from London

I’ve hated job hunting. At first it was really discouraging getting rejection emails everyday, but it doesn’t upset me anymore.

While I was at the University of Birmingham studying for a degree in accounting and finance, I was also working at a big high street bank. Since then, I’ve only had two interviews from all the jobs I’ve applied for across hospitality, retail, administration and my desired field – I want to go into business and life coaching, which I’ve now focused all my energy on.

After one, I was actually offered the job. But it was quickly revoked, and I was told that they couldn’t afford me.

Being told that I don’t possess the ideal qualities or that I fail to meet the minimum requirements for all those jobs is confusing, because I’m more than qualified and educated enough.

Going to university seemed to be my only option. I didn't really know about apprenticeships or degree apprenticeships, and at the time I'm sure my parents didn't know about those either. The emphasis was always on giving my all and getting the best education possible.

Being the oldest of four, I like to say I’m the guinea pig. I did the exploring so that my siblings would be able to access opportunities that I may have missed out on, simply because I was not in the “right” class, race or even gender. For example, networking. I remember going on Eventbrite to find events where I could speak to people on a 1:1 level, because I didn’t really have that opportunity before university and during my undergraduate studies.

I do think race does play a part. Often businesses want to claim diversity and hire rising black talent via schemes or graduate apprenticeships, as opposed to through the traditional application process. That’s why you only find one or a handful of black people in certain businesses. I was the only one when I worked at the bank.

My friend and I wanted to do an experiment where we would change the names on our CVs and see if it would make a difference. And judging by my social media feeds, so many of my degree classmates seem to have already found jobs, even though we all share the same level of experience. It does make me question why I bothered getting a degree if no one wants to employ me.