Looking for a tough evergreen? Juniper is usually the answer

The irony did not escape me, pulling into the long-stay car park at Heathrow back in August, that I was summer-escaping to a Greek island where the sunny climes were at that time outshone by England’s own tropical weather.

But I loathe London heat – from which there is no refuge – and the first weeks of August had inflicted more than a fair share. So there was appeal in the sea breeze that tempers the island of Naxos.

I’ve written before of my despair at our increasingly warming climate and its effect upon an already dry, exposed London soil. So to skip forward: the outcome is a developing appreciation for plants that revel in waterless weather. Give me fleshy leaves and ephemeral flowers over mildewy asters; and the silver-sheen of heat-resistant hairs associated with artemisia, helichrysum and verbascum.

These plants being abundant on the scattered isles of the Aegean Sea, I made plans this summer for an uplifting Greek excursion – while Covid restrictions still allowed – sifting through the great assemblage of inviting destinations that are the Cyclades.

In the end, Naxos came out on top: for my wife on account of its unpopulated beaches; for me a singularly enticing prospect: the Alyko juniper forest, on the map a silver-green blotch along a coastline of glaring sand and stone.

This had me excited. If ever there was a plant that relishes a climatic challenge, juniper would top the list. Its own defence adaptation? Compact needles and scalelike foliage, with roots that both spread and “tap”.

I fell in love with junipers fairly recently, while writing last year’s Forest: Walking Among Trees (Pavilion Books). In desert Oregon, I witnessed the impressive (if somewhat contentious) domination of Juniperus occidentalis over the arid American West. These gnarled and frequently ancient trees (one veteran was estimated at 1,600 years old) flourish in America’s high prairie, basking where other conifers fear to tread.

Researching the same book, I came across Britain’s native juniper – Juniperus communis – similarly triumphing over exposed conditions, from the windswept ruin of a Scottish Highland chapel to the Pyrenean hills of Spain. As tree guru Hugh Johnson writes, “[juniper] desires and does almost the exact opposite of the rest of the cypress family. Where they love shelter, it loves the south slope of the hill – unmitigated sunlight.

Where they need damp luxurious leaf mould, it enjoys getting its wiry roots into mineral soil.” Unmitigated sunlight and mineral soil abound on the island of Naxos, and, having gradually multiplied over the sand, the resident juniper species at Alyko – spiky J. oxycedrus subsp. macrocarpa – offers other plants a foothold, sheltering a magical ecology of wild thyme, helichrysum and red-berried mastic. As “forests” go, this one is really something special.

Staying near wide-open Pyrgaki beach in the rural southwest of the island put us within both walking and swimming distance of Naxos’s junipers. On many occasions, afternoon sea swims culminated in an enraptured hour wandering between vigorous, twisted and often shrubby trees in the glow of pre-dinner evening.

Brushing against the seeding undergrowth – in particular the low mounds of mauve Mediterranean thyme and curry plant – released herby scents that mingled sweetly with the distinct musty fragrance of juniper; like a cedar-wood cupboard concealing an ageing bottle of gin.

On the island, these aromas are artfully distilled by local bees into a honey like no other: sweet yet dark and richly herby. Across nine Greek breakfasts, I probably consumed half a pint of the stuff but would gladly go back for more.

What I’ve come to like so much about wild junipers is at the same time their horticultural downfall: a nonconformity of physique. They are trees whose habit is so shaped by their environment that it defies uniform description. Limbs die back while others become top heavy; the main stem may shoot, creep or splay, all depending on circumstance.

As garden plants, therefore, all but the most subdued forms of juniper tend to be disregarded in favour of cultivars either reliably fastigiate or horizontal (‘Skyrocket’ and ‘Pancake’ to name prime examples).

“Be the reason what it may”, wrote plantswoman Gertrude Jekyll, who was plugging wild junipers way back in 1899; “the common juniper is one of the most desirable of evergreens, and is most undeservedly neglected”. Her case for “undeserved” lies with the tree’s variation of form, regenerative vigour and “mysterious” beauty; “a colouring as decidedly subtle in its own way as that of cloud or mist”.

What a description! To these accolades, I would also add conservational merit. Juniper habitat invariably supports one or another threatened species around the globe, from the ailing sage grouse in western America to epiphytic algae and rare lichens in Europe.

At Alyko, I walked to the humming of big, beautiful dragonflies. Putting aside its role in gin production, juniper fruit (technically a cone, not a berry) is also a food source for all manner of mammals and birds.

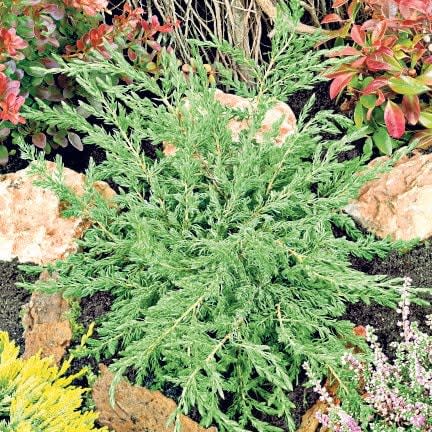

Returning to find London a little cooler than we left it, though the garden flagging after the stress of previous weeks, I made a decision to plant junipers this autumn. Where our soil is silty and sun beaten – where plants have before failed – I might start with J. communis; perhaps the bushy ‘Repanda’, which will give structure, grouped in a three or five.

As someone who prefers an atlas to a Lebanon cedar, I am naturally drawn to the glaucous hue of J. squamata ‘Blue Star’, however Juniperus ‘Grey Owl’ throws in height as well as spread, and an augmentation of that soft “mist” colouration Jekyll so enjoyed.

At the greener end of the spectrum there are the pfitzeriana hybrids ‘Mint Julep’ and ‘Old Gold’ – both architectural and large enough to form specimen plants; the latter the colour of autumnal willow. Having witnessed on Naxos what beauty can develop in the shelter of anchoring junipers, I feel a rejuvenated energy with which to face next year’s sunshine. Just allow me these cooler months to get my defences in place…

Matt Collins is head gardener at the Garden Museum in London. Instagram: @museum_gardener

How to grow juniper

Plant

Junipers require free-draining soil, but will tolerate most types and pH levels. They are happy out in the open, exposed to wind, full sun and sub-zero winters. Heavy snowfall should be cleared from branches, however, to avoid lasting damage.

Care

Junipers are the ultimate low-maintenance plant. As slow-growing evergreens, they produce very little debris; prune whole stems in autumn if necessary to refine shape and spread.

Companions

In dry gardens junipers often find themselves planted in the company of plants such as Stipa gigantea, Eryngium yuccifolium and ornamental sages. However, mass plantings of differing green-grey cultivars can soften a landscape or serve as underplanting for larger conifers.