Liz Truss’s mini-Budget has done little to unite the Tories

If Liz Truss had hoped her unofficial first Budget would prove enough to unite the Conservative Party behind her, she only had to look over her shoulder in the Commons chamber to get her answer.

Rishi Sunak, the man who dismissed her economic plan as a “fairytale”, was nowhere to be seen. Having spent much of the week chewing the fat with MPs in Parliament’s tea rooms and cafes, he stayed away from his rival’s big moment.

The sight of Mr Sunak cheering or even nodding from the backbenches would have been a powerful signal to his supporters to get behind Ms Truss.

Instead, his absence confirmed what Tory MPs already knew – the Prime Minister is on borrowed time as far as a large rump of the parliamentary party is concerned.

“People will keep their mouths shut for now,” one Sunak supporter said. “But she has just taken one of the biggest political gambles since the Second World War – and she is doing it without the support of a lot of MPs who backed others for leader, and even without the support of some of her own people.

“The fact is that if this plan fails it will burn the Conservatives’ reputation for economic competence for an entire generation. It feels existential.”

The Right of the party, and the majority of Conservative members, will be delighted with the most true blue “fiscal event” since the days of Margaret Thatcher.

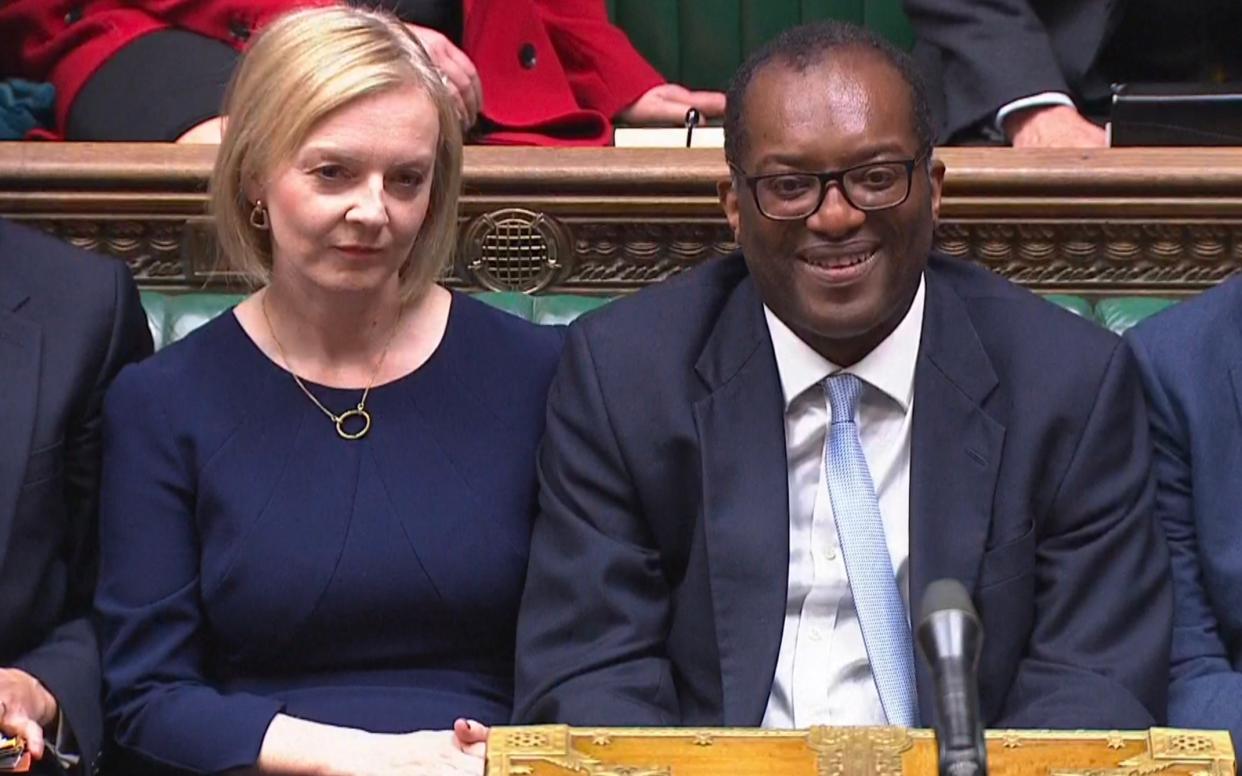

By boldly cutting taxes, fostering investment and helping homebuyers, Ms Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng, her Chancellor, have introduced the sort of policies that grassroots Tories have long been crying out for.

Ms Truss knows that Labour, and those on the Left of her party, will forever accuse her of helping the rich, not the poor, and she has made a merit out of saying she is prepared to take unpopular decisions, just as Thatcher did.

If Trussonomics proves a success, she can expect to win a record-breaking fifth consecutive term in office for the Tories. If it backfires, “we will be back to 1997”, as one backbencher put it.

Ms Truss and Mr Kwarteng have bet the house – and their own careers – on an economic philosophy they have both shared since they were newly-elected MPs in 2010 and got together to write the political treatise Britannia Unchained.

In it, they argued, as they do now, that the only way to stimulate economic growth is to create a low tax, low regulation economy that attracts investment, encourages entrepreneurship and rewards wealth creators.

They have not entirely abandoned Boris Johnson’s concept of levelling up (investment zones in traditional Labour areas are designed to create jobs), but such bold moves as scrapping the cap on bankers’ bonuses and abolishing the 45 per cent top rate of income tax owe more to the theory of trickling down than levelling up.

Some Tory MPs have already gone public with their criticisms. Julian Smith, the former Cabinet minister, said that “a huge tax cut for the very rich at a time of national crisis...is wrong”.

Sir Roger Gale said the mini-Budget “looks very high-risk indeed” and that “fortune favours the brave, but not the foolhardy”.

Mel Stride, the Conservative chairman of the Treasury select committee, said there was a “vast void at the centre” of Mr Kwarteng’s statement because it had not been accompanied by a forecast from the independent Office for Budget Responsibility.

John Glen, the former Treasury minister, said there were “irreconcilable realities” in the plans, because interest rates and inflation were rising at the same time the Government plans to borrow more money to fund tax cuts.

According to the Resolution Foundation think tank, 65 per cent of the gains from the tax cuts announced by Mr Kwarteng will go to the wealthiest 20 per cent of households, who will be better off by £3,090 on average.

Even more strikingly, 45 per cent will go to the richest five per cent, who will be £8,560 better off on average, while the poorest half of households will get 12 per cent of the tax gains, making them £230 better off on average.

The Truss/Kwarteng mantra is that when the wealthy are better off everyone is better off because it creates growth, which creates employment, which increases the tax yield, which pays for public services. The perfect virtuous circle.

Supporters of Mr Sunak worry that, by steering to the right and opening up a clear ideological gulf with Labour, Ms Truss has played into Sir Keir Starmer’s hands.

“Until now, Labour have been boxed in,” said one. “They couldn’t go to the Left because we already had the highest tax burden in decades, and they couldn’t go to the Right because they would have risked being more right-wing than the Tories.

“But now there is space for them to move – they can talk about raising taxes without it seeming reckless, and they can move into the centre ground that we have vacated.”

Sir Keir does not have long to wait before he can deliver his verdict on Trussonomics, with the Labour Party Conference starting this weekend. Intriguingly, Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, steered clear of criticising the tax cuts; Sir Keir is keen for Labour to be seen as the party of business, so his attack will be more subtle.

The 45p tax rate has, after all, only existed for nine years, and scrapping it merely restores the top rate of tax to what it was under New Labour.

Before April 2010, the highest rate of income tax was 40p. Gordon Brown introduced a 50p top rate of tax just weeks before the general election that he went on to lose to David Cameron, effectively booby-trapping the tax system for his successor.

Every time the Tories talked about abolishing the new 50p rate and restoring the top rate to 40p – as it had been for 13 years under Tony Blair and Brown – Labour accused them of wanting to help the rich.

Partly hamstrung by being in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, George Osborne compromised by cutting the top rate to 45p in 2013, where it has remained ever since.

If Sir Keir wants to be taken seriously by the business world, he must think carefully about reinstating a tax rate that even Blair and Brown did not genuinely believe in.

Not all Sunak supporters are turning their backs on Ms Truss. One accepted that “it will increase support for her because we are giving away money, which is always a popular move”, while another said: “We can’t go back to writing no confidence letters to Sir Graham Brady. We have got to unite behind her, because if we don’t we’re screwed”.

Others worry that the Government has not yet announced any plans to cut public spending, which is the traditional Conservative way of funding tax cuts. Tens of billions are already being borrowed to fund energy bill rebates, and Mr Sunak is fond of saying that “you can’t borrow your way out of inflation”.

It is not only Sunak supporters that Ms Truss has to worry about in her own party. Some of those who backed her remain “apoplectic” that they did not get the promotions they were promised, complaining to colleagues that “she has promoted an idiot instead of me” because they were more slavish in their support.

Ms Truss failed to reach out across the party, even telling Grant Shapps, a backer of Mr Sunak, that he was one of the most capable Cabinet members and one of the best communicators in Government, only to sack him as transport secretary to make room for her own disciples.

Some believe another leadership challenge in the next year is not impossible, particularly if the cost of government borrowing goes up and Ms Truss’s plans become unaffordable.

The prevailing view, however, is that her opponents within the Conservative Party will simply sit on their hands and wait for events to play out, for better or worse.

With just two years until the next general election, changing Tory leader for the third time in three years would surely be indefensible, and Ms Truss’s detractors know that their only chance of staying in power is for her economic plan to be a success, whether or not they agree with it.

Even her staunchest critics acknowledge that Ms Truss could get lucky. If a peace deal is reached in Ukraine – or Vladmir Putin is toppled – the cost of living crisis will ease because of petrol and energy prices tumbling.

That, in turn, would cool inflation, and when the income tax cuts come into effect next April people might suddenly find themselves much better off.

There is also an expectation that next May’s local elections could provide a fillip for the Government, because seats that were lost in Theresa May’s disastrous 2019 local election will be regained.

Boundary changes that come into effect in July next year will also marginally favour the Tories. Ms Truss could even decide to call an early general election if all of those factors go in her favour, though she has publicly stated that the next election will be in 2024 and the full effect of Mr Kwarteng’s growth stimulus will not have been felt by then.

For a Conservative leader to preside over a divided party is nothing new. Thatcher, Major, Cameron, May and Johnson all inherited battles with their backbenchers over the European Union, which in some cases ended their careers.

Ms Truss has created a fight all of her own, but it is one she is convinced she can win – and by adopting an all or nothing strategy she has made all Tory MPs dependent on her success.

For Conservative voters, the alternative does not bear thinking about.