Legacy: Photographs by Vanessa Bell and Patti Smith, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, review:

Being a member of the Bloomsbury group doesn’t always help your reputation. Now remembered as much for their tangled love lives as their experimental work, Bloomsburies can inspire a degree of hostility for their perceived snobby elitism. Certainly, it’s hard to credit the fact that the painter Vanessa Bell – sister of Virginia Woolf - has never had a major solo show till now.

But Bloomsbury also has its ardent fans – and Bell has one in Patti Smith. The singer and poet has long loved Charleston, the Sussex farmhouse where Bell lived from 1916 with her sometime lover, artist Duncan Grant, and which they spectacularly decorated, painting almost every available surface. Legacy, a small exhibition of Smith’s photographs displayed alongside Bell’s own, accompanies the show of her paintings, and draws these two seemingly unlikely women together.

Smith’s pictures are unflashy, unassuming black and white Polaroids. She wanted to emulate a simple, old-fashioned aesthetic, having a particular love of “the amateur photography of the 19th century, because of its stillness, its timelessness.”

Her photographs may be small, dark, simple little things, yet they do have their own quality of stillness and, in capturing Charleston (a chair, a bed, a jar of paintbrushes) long after Bell and Grant lived there, also achieve a certain haunting timelessness.

A Seventies punk pioneer and androgynous New York rock icon may at seem a far cry from an upper-class painter and her English country house. Yet by pairing the two women, this show helpfully reminds us of just how radical Bell, and the Bloomsbury group, were. Their experiments in art, living and loving were ahead of their time; it’s no wonder Smith is inspired by her, and her home. For Smith, the house is a document of truly creative lives, where “art was part of everyday living.”

And for Bloomsbury, and Bell especially, there was no contradiction between the domestic and the radical. The commitment to finding new ways of living extended from artistic, literary and intellectual experimentation to – as has been made much of – the bed-swapping, anything-goes relationships. And in Charleston, Bell united art and life, the abstract and the decorative.

Black and white photos seem a curious choice for capturing Charleston, failing to reveal the vivacity of its decoration. But Smith’s images are often textured with mottled shadow and fractured light, giving a pleasingly impressionistic image of the house and landscape.

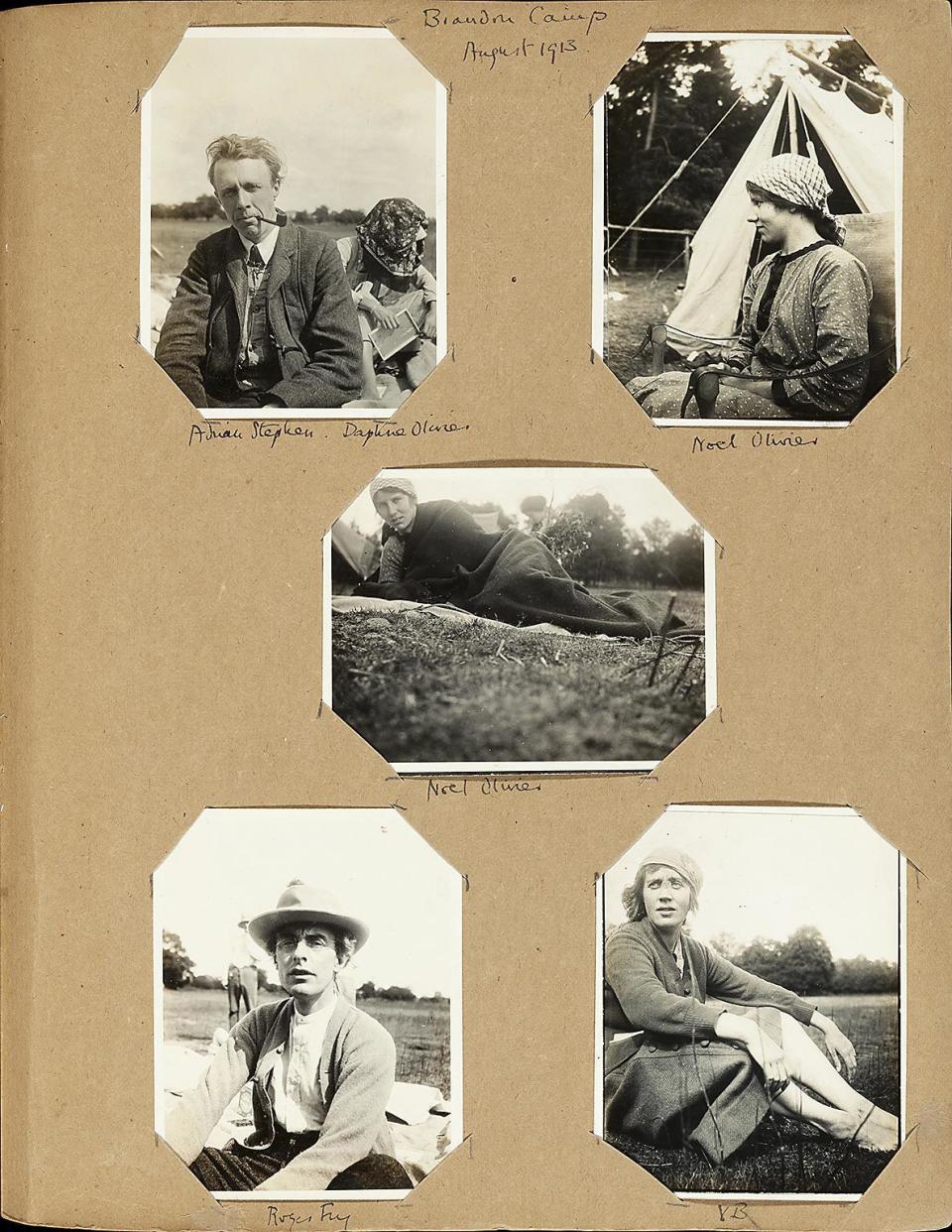

This small show is fleshed out with Smith’s photographs of the graves of other artistic heroes (Keats, Yeats, Blake, Plath), which lends an unfortunate whiff of morbid teenage fandom. But Legacy also features Bell’s photograph albums, mostly images of people; she loved the camera’s ability to capture fleeting moments of being. There’s an elegiac contrast between her albums, stuffed with intimate images of her friends and children, and Smith’s attempt to capture a ghostly artistic afterlife: the sense of creativity that even an empty place can still hum with.