The Least We Could Do Is Send the Little Children Home

"Kill the Indian in him and save the man."

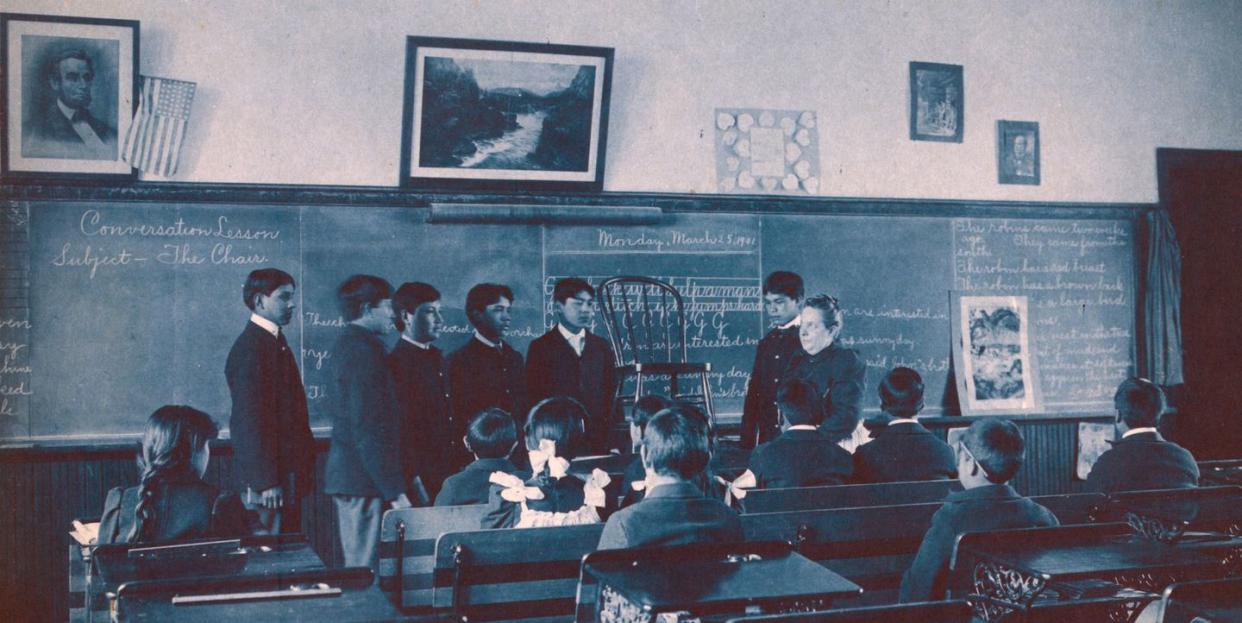

That was the official policy statement of the United States government, after it had employed only the first half of the formulation for decades in order to pacify the Indigenous people from whom we were 'jacking the continent. It originated with an Army officer named Richard Henry Pratt, who founded the Carlisle Industrial School, the boarding school made famous by the fact that Jim Thorpe went there. In 1892, Pratt delivered a paper describing how he planned to fulfill the second half.

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man…We shall have to go elsewhere, and seek for other means besides land in severalty to release these people from their tribal relations and to bring them individually into the capacity and freedom of citizens.

And that certainly was mighty white of R.H. Pratt.

At their peak, there were some 61,000 children in 367 boarding schools in 29 states. The process of killing the Indian in them was brutally carried out, both here and in Canada. Their native languages were suppressed, often through beating and starving the offending students. From National Geographic:

For many, the schools were hotbeds of humiliation, abuse, and victimization. They were also dangerous. Unsanitary conditions and overcrowding fueled communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, influenza, and smallpox, especially among students weakened by trauma and meager rations. Schools had their own cemeteries—and students often built their classmates’ coffins. Other children died by suicide or ran away. The practice was so common that some schools offered bounties for runaways. “The temptation to return to their wild life, with the savage influences surrounding them, is no doubt very strong,” wrote one newspaper reporter in a lengthy article about life at White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Indiana…

For several years now, in Canada and then in the U.S., attempts to discover the graves of the Native children who died at these schools have been undertaken. The results have been horrific. Hundreds of unmarked graves have been discovered in both countries. Now, under the direction of Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet member, the federal government has put its shoulder into the grim business of counting the forgotten dead. Which has provided momentum to ongoing local efforts along the same lines. The most recent revelation comes from Genoa, Nebraska, where the Genoa Indian Industrial School operated for 50 years until it closed in 1934. From the Omaha World-Herald:

A collaborative effort has thus far found 102 names of students — primarily young children — who died while at the school, which operated in Genoa, Nebraska, from 1884 to 1934. Some of the names might be duplicates, but the true death toll is likely much higher, said Margaret Jacobs, a professor of history at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and co-director of the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project. The project, formed in 2017, has focused in recent months on identifying students who perished at the school.

They have the names. They don’t yet have the cemetery—or, more likely, the burial ground, because gravestones are a real long shot in these situations.

Guided by a 1920 Nance County plat map that denotes the cemetery’s location, three areas have been searched using ground-penetrating radar in recent weeks, according to Judi gaiashkibos, executive director of the commission. Data gathered from the searches will have to be further analyzed, but field observations did not detect anomalies consistent with graves.

It’s disheartening, gaiashkibos said, that the graves haven’t yet been found. “I think America needs to take these little children back home, and if we’re not able to find them, I think we need to do something to recognize that they lost their lives there,” said gaiashkibos, a citizen of the Ponca Tribe.

This is truly god’s work they’re doing. There aren’t many avenues through which the government can atone for its relentless genocidal policies toward Native populations, but, certainly, sending their lost children home is very much the least we can do.

You Might Also Like