The Last Thing the United States Government Wants Is Abu Zubaydah Testifying in a Courtroom

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard the case of United States v. Zubaydah, a cancer on the American rule of law that has been metastasising through the judicial system for almost 20 years. Let’s remember now who Zubaydah, one of the first people who fell into the Bush Administration’s torture regime, actually is, and what happened to him. From the Washington Post:

The government still contends Abu Zuba[y]da is a terrorism suspect and was a close ally of Osama bin Laden. But he denied ever being an al-Qaeda leader, and it seems clear now he was not nearly the prize the U.S. thought when he was captured in 2002. What is known is that he was held at so-called “black sites” in Thailand and Poland and extensively tortured: he was subjected 83 times to waterboarding, a technique that leads victims to believe they are drowning. He lost an eye. He has testified that he was told by doctors he nearly died four times.

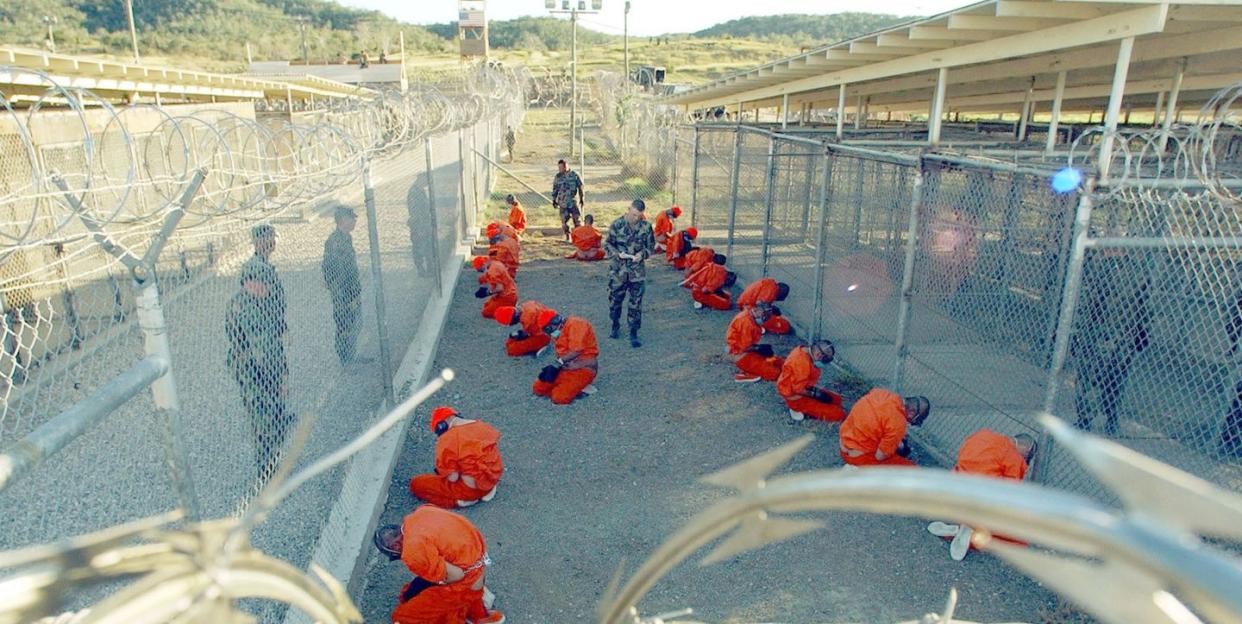

Zubaydah also was confined to a coffin-sized box for hours at a time, was subject to sleep-deprivation techniques, and now is pretty much a breathing advertisement for the existence of an International Criminal Court. He and his lawyers have sought some sort of legal recompense for years now, and he’s been an inmate at Guantanamo for the past 15 years, and he’s had a habeas corpus petition pending in a Washington court for 14 of them.

Zubaydah was whisked off to so-called CIA “black sites,” first in Thailand and then in Poland, and it was his treatment at the latter that was the business of the Court on Wednesday. Poland is conducting its own investigation into what the United States did on its soil, and Zubaydah’s legal team is seeking information for the purposes of that investigation. The lawyers also want to solicit the testimony of the two infamous CIA contractors, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, who got rich developing the torture program in the wake of 9/11.

All of which has gotten up this government’s nose a very long way. Unfortunately, they went into Court on Wednesday arguing that a “state secrets” policy applied to information that’s been public for years. The two contractors have talked—nay, boasted—about their work in a number of venues. From the Washington Post:

A district judge dismissed the case, but a divided U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit said the judge did not do enough to untangle information that could be revealed and that which the government legitimately could withhold.

As one judge put it, before there can be a state secret there must be something that remains secret. At the Supreme Court, the justices asked Fletcher how the government could invoke the state secrets privilege, which the court first recognized in the 1950s, on information already known.

At one point, Justice Elena Kagan asked, quite logically, how the government could plausibly argue that information of the black site in Poland was a state secret when the government itself in open Court kept talking about Poland. Kagan found this to be “farcical.”

I mean, if everybody knows what you’re asserting privilege on, like, what exactly does this privilege—I mean, maybe we should rename it or something. It's not a state secrets privilege anymore.

Zubaydah’s lawyers at least were not subject to the fundamental illogic afflicting the government’s case.

I understand the argument about our relationships with our allies and it not necessarily being coextensive with the question whether something is a secret. But, at—at a certain point, it becomes a little bit farcical, this idea of the assertion of a—a—a—a privilege, doesn't it?

For his part, Klein said he did not need to ask the CIA contractors specifically whether there was a detention site in Poland.

“The Polish prosecutor already has information about that and doesn’t need U.S. discovery on the topic,” Klein said. “What he does need to know is what happened inside Abu Zubaydah’s cell between December 2002 and September 2003. So I want to ask simple questions like, how was Abu Zubaydah fed? What was his medical condition? What was his cell like? And, yes, was he tortured?”

In truth, regardless of their respective ideological bents, the justices seemed truly bumfuzzled as to what to do with this case. They all acknowledged in one way or another what Kagan was talking about, but they were completely at sea as to what to do about it. Then, virtually at the last minute, Justice Neil Gorsuch swooped in to the rescue.

JUSTICE GORSUCH: Mr. Fletcher, I don't want to interrupt you later --

MR. FLETCHER: Please.

JUSTICE GORSUCH: -- so I'm just going to do it up-front.

Why not make the witness available? What is the government's objection to the witness testifying to his own treatment and not requiring any admission from the government of any kind?

This caught Acting Solicitor General Brian Fletcher flatfooted. There was a bit of the old hummina-hummina from Fletcher, but Gorsuch saw an escape route for the Court and he wasn’t going to let it pass.

I understand there are all sorts of protocols that may or may not, in the government's view, prohibit him from testifying. But I'm asking much more directly, will the government make the Petitioner available to testify on this subject?

The other justices saw the opening Gorsuch had cracked and piled on through it. First, Justice Stephen Breyer asked the same question that Gorsuch had asked, and then Justice Sonia Sotomayor joined in the questioning, and even Justice Samuel Alito was intrigued. Fletcher, dancing as fast as he could, ended up essentially pleading nolo on the idea.

To represent the legal position of the United States, but in doing that, it's important to me, as it always is, to make sure that I'm representing my clients with full consultation of what's being put before them. I understand the question. And because this is not an issue that has been in this litigation up until now, I'm not prepared to make representations for the United States especially on matters of national security.

Clearly, this was not an option that Fletcher and the government lawyers remotely had contemplated. Of course, the last thing it wants is Zubaydah in a courtroom, either because of what he could testify to regarding his own treatment, or because he has been rendered incompetent in a way that would be its own testimony in that regard. His wounds would be his witnesses, and we can’t have that.

You Might Also Like