Kurt Vile interview: 'I'm hypersensitive to the world, my brain gets scattered pretty quick'

“You guys are being a little weird,” Kurt Vile says to his daughters Awilda, eight, and Delphine, who is almost six. Awilda climbs onto Vile’s shoulders in the sun room of the family’s house, which prompts Delphine to ask him to lift her by the arms and flip her over. They are talking about their butts.

Vile, his wife Suzanne Lang, and their two home-schooled girls live in a house smartly decorated with mid-century modern furniture, in the Mount Airy section of Philadelphia, bordering the forest-like 1,800 acre Wissahickon Valley Park.

“We’re in Philly, but we’re next to the woods, somehow,” says Vile, who grew up in a nearby suburb. “Which is not easy.”

“I got a tick before,” Awilda says. “Remember, Daddy?”

“I wasn’t here. Where was the tick?” asks Vile, who is wearing a Waylon Jennings T-shirt, jeans and purple sneakers.

“I was like, ‘Mom, there’s something on my butt!’”

Awilda exclaims to general laughter: “It was huge!”

Vile’s family, like his songs, is comfortably offbeat. This 38-year-old singer, guitarist and songwriter, who looks and seems younger, is the nearest thing rock music has these days to a consensus. He blends well with artists from one generation back (he’s toured with Dinosaur Jr and The Flaming Lips) and even earlier artists (he’s opened for Neil Young and John Prine, and performed with Cyndi Lauper and John Cale). He’s recorded with the goth ballad singer Hope Sandoval, the alt-country group The Sadies and the elite Saharan blues band Tinariwen.

Yet Vile isn’t a household name. He’s more like weird underground rock’s emissary to the mainstream. Lorde put his “Society Is My Friend” on a Spotify playlist of her favourite songs. The country star Keith Urban expressed amazement at Vile’s 2015 breakout hit “Pretty Pimpin”, saying: “It sounds like pure stream of consciousness.” In the last few years, at major music festivals, Kurt Vile – improbably, it’s his real name – has been as constant a presence as flower crowns and vaping.

“I think all those older artists spot that he’s the next person on the timeline,” says Tom Scharpling, host of The Best Show, a weekly streaming radio program on which Vile is a frequent guest. Scharpling, who also directed the video for Vile’s “KV Crimes”, adds: “He’s the real deal – music isn’t a means to an end so he can explore his passion of, say, restoring furniture.”

Vile’s new album, Bottle It In, will be released on 12 October. His most consistent to date, it sharpens and deepens his sound. He writes ramshackle songs with loping tempos, and hangs behind the beat while drawling quizzical lyrics that search for wisdom, epiphanies or comedy in the mundane. His appeal rests not only in versatility and the kind of authenticity that only lengthy guitar solos can establish, but also in inscrutability. His music is personal – the “I” in his songs, he says, is almost always himself – but not revealing, which makes him a trusted figure in an era when, to many people, charisma feels corny, manipulative or striving. You can’t grow sick of music you only partly understand.

Vile doesn’t exactly tell you about himself. He ducks in and out of clauses when he talks, leaving thoughts and insights unfinished, averting his glance behind a parted curtain of hair. He reveals certain details of his life – he thinks he has undiagnosed attention deficit disorder; he has meltdowns when he’s under stress – but doesn’t fully explicate them.

His daughters, however, know everything and are prepared to share it with a visiting stranger. “Daddy calls us so much when he’s on tour,” Awilda says. “I’ll be like, ‘Ugh, Daddy’s calling again?’”

And if Lang doesn’t answer, Delphine adds helpfully, he gets anxious and phones a neighbour.

“I’ve only done that twice,” Vile says, flushing a bit. “It’s weird when you’re out there. Your mind goes flying. I’m hypersensitive to the world.”

Lang, a practitioner of alternative ayurvedic medicine, who has asymmetrically cropped hair and a wide, steadying smile, was 16 when she met Vile, then a 14-year-old skateboarder who had trouble paying attention in school. Her sister called him Tigger, after Winnie the Pooh’s fidgety friend. “Kurt bounced all over the place, and he was a little nervous, too,” Lang recalls.

“I’m still a little nervous,” Vile murmurs.

“Aren’t we all?” Lang says sympathetically.

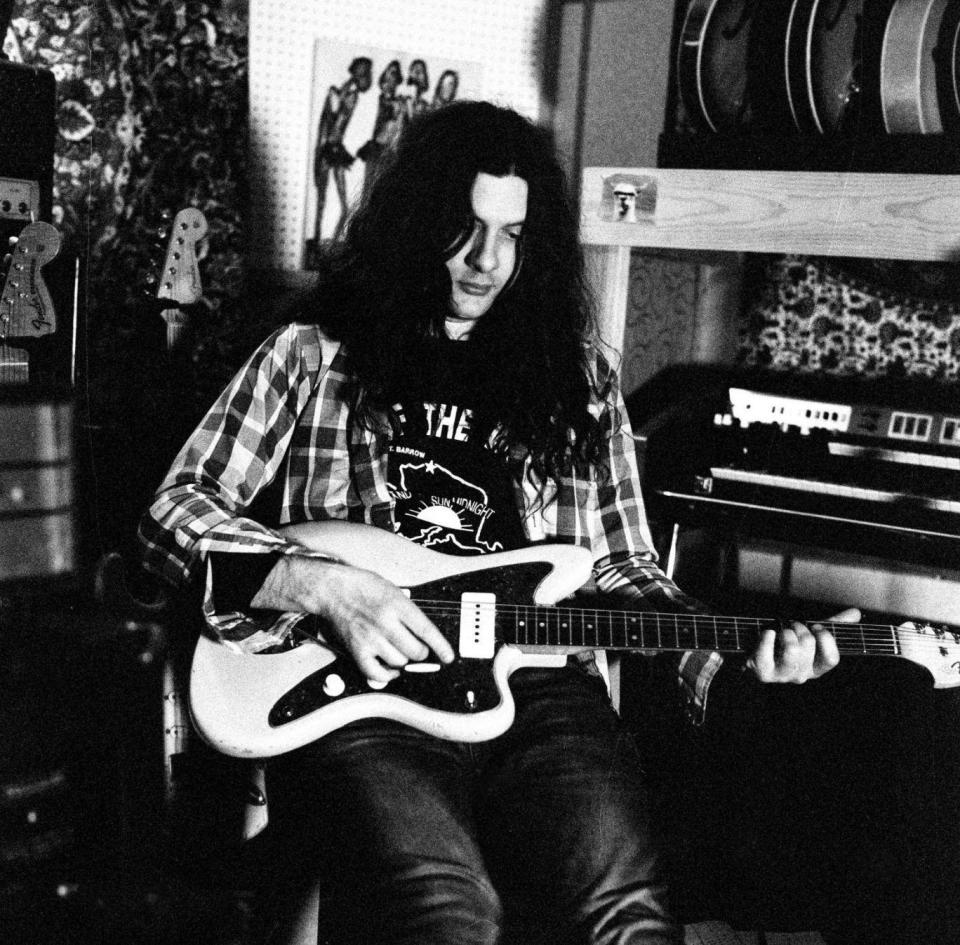

When Vile and Lang married in June 2003, he gave guests a homemade CD-R of his music called Ten Songs. For years, he recorded his work on home audio equipment and tried to get anyone to notice. With his unkempt hair and plaid shirts, he looks like a grunge bassist, or a roadie, the role he played this year in a Portlandia cameo. (Vile’s best line, which he delivered expertly, described a pressing need to use the bathroom.) But he’s as determined as his manner is indolent.

Vile’s father, Charlie, drove trains for Philadelphia’s regional transit system and loved bluegrass, especially Doc Watson. When Kurt turned 14, his dad gave him a banjo, which replaced skateboarding as an obsession. Vile, the third of 10 kids, was a weirdo, he says, “but not too weird, only as weird as awkward teens growing up in the grunge era, trying things out.” He played trumpet in the school jazz band, switched from banjo to guitar, and began studying indie rockers, especially Pavement, Beck, Sonic Youth and Dinosaur Jr.

After high school and a period of uncertainty, Vile moved to Boston to join Lang, who had graduated from Dartmouth and enrolled at Emerson College, where she earned an MFA (Master of Fine Arts) in poetry.

In Boston, he drove a forklift and unloaded tractor trailers. “I showed up, awkward, in my twenties,” he says. He didn’t blend in well with his co-workers. But Vile also met college students who educated him about artists he’d never heard, including Brian Eno and John Fahey. “So I got the college experience without going to college,” he says. “I smoked pot and listened to weirder music than I would have at home.”

When the couple moved back to Philly, Vile operated a forklift at a local brewery and met singer Adam Granduciel, who had recently moved from Oakland, California. The pair bonded over their love of Bob Dylan and Neil Young. For a while, Granduciel played in Vile’s band, The Violators, and Vile played in Granduciel’s group, The War on Drugs.

In 2008, already in his late 20s and still working at a brewery, Vile signed to a small label and released his first official album, which he cheekily called Constant Hitmaker, a nod to the subtitle of The Rolling Stones’s American debut LP, England’s Newest Hit Makers.

He knew the boastful title would annoy people, but he also meant it — Vile wanted to write hit songs. “Granted, those songs weren’t in the charts,” he says. “I feel like, deep down, everybody wants a real song, with emotion and that familiar classic thing, and I was going for that with...” His voice trails off into a puff. “I’m, like, losing my speech here. I think I had a stroke,” he says and laughs.

Meg Baird, a singer and guitarist who has recorded and toured with Vile, said he is “confident, in a way – but he’s also not”, adding: “Even in his stage presence, there’s mystery. He’s hiding behind the hair. But his music has such a strong presence, and he hasn’t shied away from success. An unconfident person wouldn’t be able to do that.”

Vile was fired from the brewery in 2009 for demonstrating too many mixed feelings about his job. Shortly after, he was signed by Matador Records, the label that had released the Sonic Youth and Pavement albums he’d loved. Bottle It In is his sixth Matador album, following a collaborative LP with Courtney Barnett.

Putting out rock music on an indie label in 2018 isn’t a surefire way to become a superstar, yet Vile says he craves a large audience: “I like the idea of getting bigger. I do want more success.”

“Pretty Pimpin” went to number one on Billboard’s adult alternative chart, where it sat among Mumford & Sons and Coldplay tracks, and Vile anticipates releasing several singles from Bottle It In.

“We’re going to try to pull a Bruce Springsteen, Born in the USA, and just, you know, keep putting out hit singles,” he says, more in earnest than in jest.

The themes of his songs, however, aren’t quite conducive to mass appeal. His lyrics often describe events that defy physics and echo the cosmic musings of 1960s psychedelic rock, which leads people “to label Vile a spaced-out stoner,” according to Pitchfork.

In “Bassackwards”, the first single from Bottle It In, he sings: “I was on the moon, but more so, I was in the grass, so I was chilling out, but with a very drifting mind.”

“That’s not drugs, that lyric,” Vile says. “That’s more being in space from, you know, the weight of the world. Stress is often part of it. Being in a fog because of all the things I’ve got to do.” He adds: “I’m not, like, a heavy drug user at the moment.”

In “Wild Imagination”, a revealing song from his 2015 album, b’lieve i’m goin down, he describes a hallucinatory image he’s having and wonders whether others can imagine it too. Vile knows he’s got an oddball mind. And while songs are good when they’re enigmatic, interviews are not.

“My brain gets scattered pretty quick,” he says. “Depending on what you want out of me, that might be a pain in the ass.”

A few weeks later, I email some questions to Vile, in the hope of understanding him better. In response, he writes about his fear of death, especially during the “high trauma” of being on an aeroplane, and says: “I think life is equally beautiful and hilarious at times just as much as it is often completely terrifying.”

I also, quite unfairly, ask him how I should end this article. In his reply, he says that every day for years, he ate two eggs over easy for breakfast, but now he hates them for breakfast, and eats them only at lunch.

“Is this a riddle?” he asks. “What should the last paragraph of your article about me be? Heh heh... looks like the ol’ KV has stumped ‘em again, boys.”

By continuing to confuse me, this answer gave me some clarity. His replies weren’t riddles – they were clues about not believing in certainty. Vile is a philosopher in search of philosophy, happy to keep looking.

© New York Times