If your kids ask for a Yes Day, should you just say no?

It is 8.04am and so far today I have already... been to the corner shop to cater for my children's arcane breakfast requests; made said children chocolate and banana pancakes; had my face painted with nail varnish (blue and glittery pink); and allowed one child to draw on his school uniform with multi-coloured permanent markers.

It must be lunchtime by now, I think. But, no, there are still many hours to go - hours in which my husband and I will watch mind-blowingly inane television shows about slugs with violent superpowers, witness our children destroy the kitchen and, at some stage, break almost every minor rule we have ever set.

Welcome to the "Yes Day", a seemingly masochistic parenting trend thrust into the limelight last week by the Hollywood star Jennifer Garner. Having recently joined Instagram, the actress and former Mrs Ben Affleck - mother to three children aged 11, eight and five - posted a photo of herself looking gorgeously dishevelled along with the caption: "You'll never need coffee more than the day after 'Yes Day!' #wesleptinatent #inthebackyard".

Garner and her children have, it turns out, been practicing Yes Days for five years. The rest of us must now scramble to catch up. So here is the deal: you must put aside 24 hours in which you agree to say "yes" to all your children's requests. All of them.

Garner's annual tradition was, ahem, garnered from a children's picture book from 2009 called Yes Day! by Amy Krouse Rosenthal and Tom Lichtenheld, which charts a day in the life of a small boy, "a day when every answer is yes". The pint-size protagonist wakes, asks for pizza for breakfast, and gets it. He wants to gel his hair into punkish spikes for the family photo, and so does. He wants to postpone cleaning his room, so it stays a stinky mess.

So far, so harmless. Ominously, however, a great number of his requests revolve around junk food. He piles a shopping trolley high with luminous cereal boxes and then heads straight to an ice cream parlour. The authors don't make the ensuing sugar-rush explicit, but the next thing he does is have a food fight.

And so to the start of our own Yes Day, where the chocolate pancakes are laid in front of my six and three-year-olds. "Can I have honey on them?" asks my son. "Sure." "Bit more?" "Ermmm, OK, but they're going to be horribly sweet." "Bit more again?" Soon the pancakes are literally floating. "They're a bit... sweet," says Johnny (the six-year-old), "I'm going to leave them, OK?" The pancakes are plonked in the bin.

Fifteen minutes later, we are passing a local café. "Can we have a couple of those chocolate muffins? You know, the REALLY BIG ones?" asks Frida. Approximately one-tenth of the muffins is eaten before the rest is binned. Unpoliced, it turns out, my children go about stuffing themselves with sugar and throwing money into the wind. Is this how it's supposed to pan out?

The subtext is that the parents are going to do their best to be as loving as they can be

I consult Hannah Lamdin, a mother of two and a Yes Day veteran. "I felt it was more an experiment for me than for the children," she says. "I was stuck in a phase of saying 'no' all the time and arguing with a demanding toddler near constantly, so I wanted to try to change things." The experiment worked, she believes. "It's made me more aware of how much I'm saying no and making our lives less fun, and whether I'm saying no for the right reasons or just because I can't face the cleaning up."

Rosenthal's book makes exactly this point. The inside cover is decorated with a calendar, on which each day of the month is marked with a different expression of "no" - "Not Gonna Happen Day", for example, and "Not Today Day" - with the tantalising exception of the final day of the month, which is marked "YES DAY!"

It's a cute reminder that, as parents, we are forced to say "no" far more than we realise - to keep small people safe, to keep soft furnishings clean, to preserve our sanity or simply to keep to schedule. But do all these "nos" run the risk of snowballing into an automatic response, unnecessarily curtailing kids' creativity and freedom?

"Periods of intense responsiveness like Yes Days have the potential to radically change children's behaviour for the better," says child psychologist Oliver James. "But, more importantly, they allow parents themselves to change. They realise that for a lot of the time that they are getting on the child's case, it is because they are feeling ratty for their own reasons."

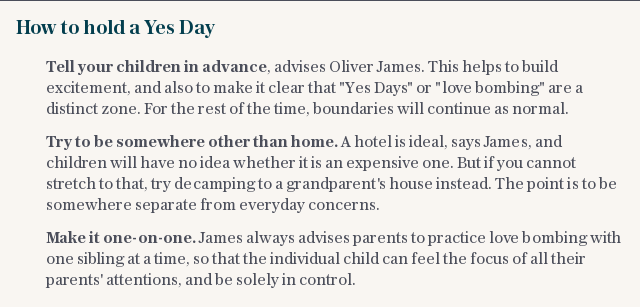

Yes Days, in fact, bear many similarities to Oliver's own strategy of "love bombing", in which he advises parents to set aside a day - or 48 hours if you can stretch to it - in which their child gets to call the shots. "It's presented to the child as a day in which he or she has control over everything that happens," says James, "but the subtext is that the parents are going to do their best to be as loving as they can be during that period."

James advocates the strategy for kids from three years old to puberty, and says that it works to address childhood behavioural problems from violence to shyness to sleeping problems. "Rewarding a child who has been acting up sounds completely counterintuitive," he says, "but the core existential problem for young children is the ghastly realisation that external reality doesn't bend to their will."

Love bombing works, he says, "because it gives the child the experience of unlimited love and control, and shows them that they don't need to kick against you all the time. I call it resetting their emotional thermostat."

In his many years of using the strategy, James claims never to have come across a child who demanded anything utterly preposterous. "I think it's because that's not what children really want. They want simple, accessible things - like your love."

So it proves in our house. We watch far more television than would usually be permitted, but the really remarkable thing is that I watch it with them, snuggled under a duvet. We go for a walk in our pyjamas. We spend too much money on chocolate, but no one demands a helicopter. We jointly devise a recipe for magic sweets, then all make a horrible mess in the kitchen and leave the clean-up job until tomorrow.

"You still have to say 'yes' to everything, right?" asks Johnny at the end of the day. "Yep," I reply. "So... can we have another Yes Day tomorrow then?"