Kate Elizabeth Russell: ‘We all participate in a culture that allows abuse to happen’

When she first read Lolita in her early teens, Kate Elizabeth Russell became obsessed with the character of Dolores Haze. “I saw a lot of similarities between her and me,” the author says, on a phone call from Wisconsin, and not just because of their age. “Some of them were superficial, like we’re both from New England, but also she’s lazy and moody and she has a good sense of humour. You can find snippets of her real personality if you read the novel closely and I did because I was always looking for her.”

It’s strange hearing someone say they were drawn to Dolores. To most readers, it never seems as though there’s much going on beneath the pale white skin, knee socks, fluttering eyelashes and thin wrists that Humbert Humbert lusts after in the cult classic about an illicit adult-child affair. But growing up, Russell read Lolita enough times that she learnt to see the girl beneath the veil of sexualisation. She recognised that Lolita was clever and had dreams and aspirations. She refers to a moment in the novel where Humbert hears the results of Dolores’s IQ test and asserts that they must be wrong because she isn’t that smart. Even though she was young, Russell remembers thinking, “No, she is that smart. You just don’t understand her”.

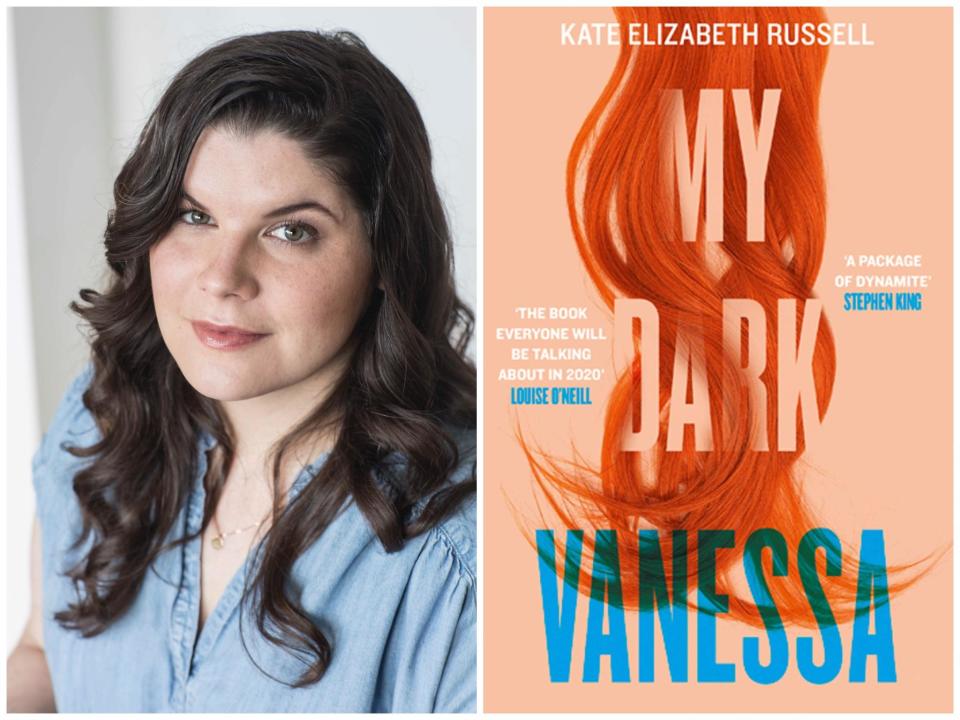

The main character of Russell’s hugely hyped, just-released debut novel, My Dark Vanessa, is obsessed with Lolita as well – in fact, the book has been called “Lolita for the #MeToo generation”. Vanessa is an awkward outsider at a new boarding school who spends her nights pulling meanings from the novel, given to her by her 42-year-old English teacher Mr Strane. His attentions soon turn from academic to physical: a hand touches a leg, a stolen glance, a body presses against another until they are stealing kisses in the blackness of a classroom locked from the inside. The chapters alternate between Vanessa as a schoolgirl and as a chaotic and self-loathing adult who spends time off from her hotel receptionist job eating takeaways and having sex with sad divorcees. In the wake of high-profile sexual abuse cases, especially in Hollywood, the story feels particularly prescient.

My Dark Vanessa is one of 2020’s biggest releases, bought at auction for seven figures. It’s also one of the most controversial. Excavation author Wendy Ortiz accused not only Russell of plagiarising her memoir about a student-teacher relationship – despite not having read the book – but the industry of paying more money for books written by white writers. In response to the allegations, Oprah removed My Dark Vanessa from her Book Club (although it has since become clear that Ortiz’s claims are unfounded). Then a juror was almost swapped off the Harvey Weinstein trial after his lawyers argued that, as they had read the novel, it could cloud their judgement. “A difficult time” is how Russell describes that period, clearly hesitant to revisit the furore(s).

But after support from literary megaliths such as Stephen King and Gillian Flynn in the past month, everything finally seems to have smoothed over for Russell – apart from the fact that her book tour has been cancelled due to the coronavirus. When speaking to Russell, her sentences eloquent and fully formed, you get the impression that, whatever happened, she knew she was onto something good. “I believed in the book,” she repeats at various points throughout our conversation. But she is also shy – to the point I suspect she is relieved about the cancelling of the book tour. She hangs up from our Skype call to ask if we can speak over the phone instead, admitting: “I’m not really camera ready right now.”

Russell, 35, grew up in a small town in Maine and spent much of her childhood with her nose in books and she also started to notice hyper-sexualisation and sexism in other areas of pop culture. “It was an insight into the way the world worked,” she explains with a sigh. After she read Lolita, she started seeing the book everywhere she looked: it was in the way men’s gazes lingered on her developing body, the way Britney Spears appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone cuddling a Teletubby doll in polka dot underwear. Or the way that intern Monica Lewinsky was called a “homewrecker” for giving the president oral sex in the oval office, even though he was 27 years her senior.

With Lolita always roving across her mind, Russell started writing her own work. The poems Vanessa writes for Strane in the book were actually taken straight from Russell’s teenage diary, and by her late teens, Strane and Vanessa were complete in her mind. But it wasn’t until Russell began a masters in creative writing that she became intent on bringing them to life. In particular, she wanted to interrogate the “grey areas” of abuse and challenge the idea of a “perfect victim” – Vanessa views hers and Strane’s relationship as a forbidden love tryst rather than sexual abuse. She does things that are disagreeable.

She refuses to be a “martyr”, says Russell. “Victims of sexual violence are often intensely sympathetic characters. Or they’re held up as these girls who were broken, but then come out of it triumphantly at the end. There isn’t much discussion of the ways the victim might internalise their abuse.”

Not everyone understood Russell’s perspective. Though she respected her peers in her writing class, she often found their feedback was at odds with her aims. “People tended to police Vanessa’s personality,” she says. “They would say she wasn’t likeable, they questioned her sexual behaviour.” Russell ignored their advice. “I wanted Vanessa to be unlikable,” she continues, “because in my mind that was the best way to access her humanity”.

For Russell, it was important that the reader becomes aware that there isn’t a “type” of person who is abused. Vanessa has a happy upbringing prior to meeting Strane, despite arguments with her Mum about algebra homework and fallouts with friends. “Characters who are abused in fiction are often incredibly poor or come from a broken home,” she explains. “We think, ‘Of course they were susceptible’. It’s a lot harder to wrap your head around the idea of a kid who came from a safe and secure home and was loved.”

Nor is Strane a one-dimensional villain. “I had to write him in a way that let the reader understand why he was so compelling,” Russell explained. For her, this makes the book more challenging: “If there’s this monster who’s working on his own, he can therefore be isolated – it’s just him that’s the problem. But if you open it up and start looking at the culture, and the context in which this kind of abuse occurs, then the complicity is spread around. I think that’s quite uncomfortable for readers because then you have to think about how you yourself participate in this culture. And that’s not to say that everyone is to blame. But at the same time, maybe we are? We all participate in this culture that allows this kind of abuse to happen in different ways.“

What does she think a Strane – or, say a Weinstein – might learn if he read her book? “A man who might relate to Strane might realise how obvious their behaviour is,” she says, “and how it can so clearly be seen as manipulative. And also that so much of those manipulations sort of follow the same playbook”.

It was only after Russell started reading trauma theory during her PhD, at the University of Kansas, that Russell realised what she was writing was not a love story but a more complicated tale of abuse, complicity and consent. Russell had grown up thinking romance meant Heathcliff and Cathy tearing each other apart in Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, or that happiness meant Jane Eyre marrying the deceptive Mr Rochester. According to Russell, “the way that we conceptualise and practise romance, and especially heterosexual romance, is very much tied to trauma”.

Russell ended up reading around 80 books focused on narratives of sexual abuse to explore her theory. She mentions Kathryn Harrison’s The Kiss, a memoir about the author’s sexual relationship with her estranged father. Also Tiger Tiger, an account of a child’s relationship with a 51-year-old paedophile. Similarly, My Dark Vanessa does not shirk away from graphic details. Strane makes Vanessa dress up in pink strawberry-printed pyjamas; in another moment, he walks around her childhood bedroom and grins at the girlish details – a Beanie Baby on her shelf, a ballerina popping and spinning out of her jewellery box.

Russell says that she eventually acclimatised to writing about such dark subject matter. “I worked on the book for such a long time that I got used to it. I’m like, ‘This is what writing is, it’s just feeling terrible’.” She laughs, but it doesn’t sound like she’s finding anything funny.

“But it was tough,” she continues. “Often I would feel physically exhausted, as though I had done an intense workout, when all I had been doing was sitting and writing.”

It must have been especially hard given that the author is herself a survivor of abuse. After Ortiz accused her of being the wrong person to tell this story, Russell made a statement on her website confirming that the book drew from experiences she’d had as a teenager but adding: “I do not believe we should compel victims to share the details of their personal trauma with the public … opening up further about my past would invite inquiry that could be retraumatising.”

Today, Russell emphasises that it’s important for her that the book be read as fiction, not memoir. “I don’t want any thoughts of me or impressions of my background to hover over the reading process. I think that’s really unproductive,” she says. “I want the space to use my own experiences in whatever way I want without having to justify or explain myself when I do.”

How did she cope, then, writing something so close to her past? “It was important for me to take breaks,” Russell says, matter of factly. “I found walking my dog very centring and calming. I remember when I was trying to end the book, I was struggling to think of a way to tie up all the loose ends in a way that still felt realistic. My friend said: ‘Why don’t you give her a dog?’”

Russell is not Vanessa, but the author sees herself in her, just like she saw Dolores in Lolita. She knows what would make a woman like her feel better. I can feel Russell’s smile pressing into the phone receiver. “The thing I used to take care of myself when I was writing was the same thing I gave to Vanessa to make her feel better,” she says. “I like that.”

My Dark Vanessa is out now from Fourth Estate