Judas Priest’s Rob Halford on booing Thatcher and those ‘death pact’ accusations

In the summer of 1988, Rob Halford joined 40,000 LGBTQ marchers in London protesting the introduction of Clause 28. Despite being “deeply in the closet”, the then-36-year old singer of the British metal group Judas Priest felt incensed by the introduction of a law that told local councils they should “not intentionally promote homosexuality, or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality.”

As the procession wended its way past Downing Street, a chant rose in the air. “Maggie, Maggie, Maggie! Out, out, out!” Now aged 70, he tells me: “It probably was at the back of my mind that I would be outed by being there. But I guess I thought, ‘Stuff it. If I’m going to be outed, what better way than to be surrounded by my people?’ You feel invincible when you’re in that type of environment. You’re standing up for something you believe in so strongly that whatever happens outside this day, or this moment, doesn’t have any great consequence.”

“But who knows what damage could have been done by me being on that march?” he adds. “I was constantly told to dial it down a bit – that it wasn’t a good idea for me to hang out in the gay bars in New York, or whatever – to just be careful.”

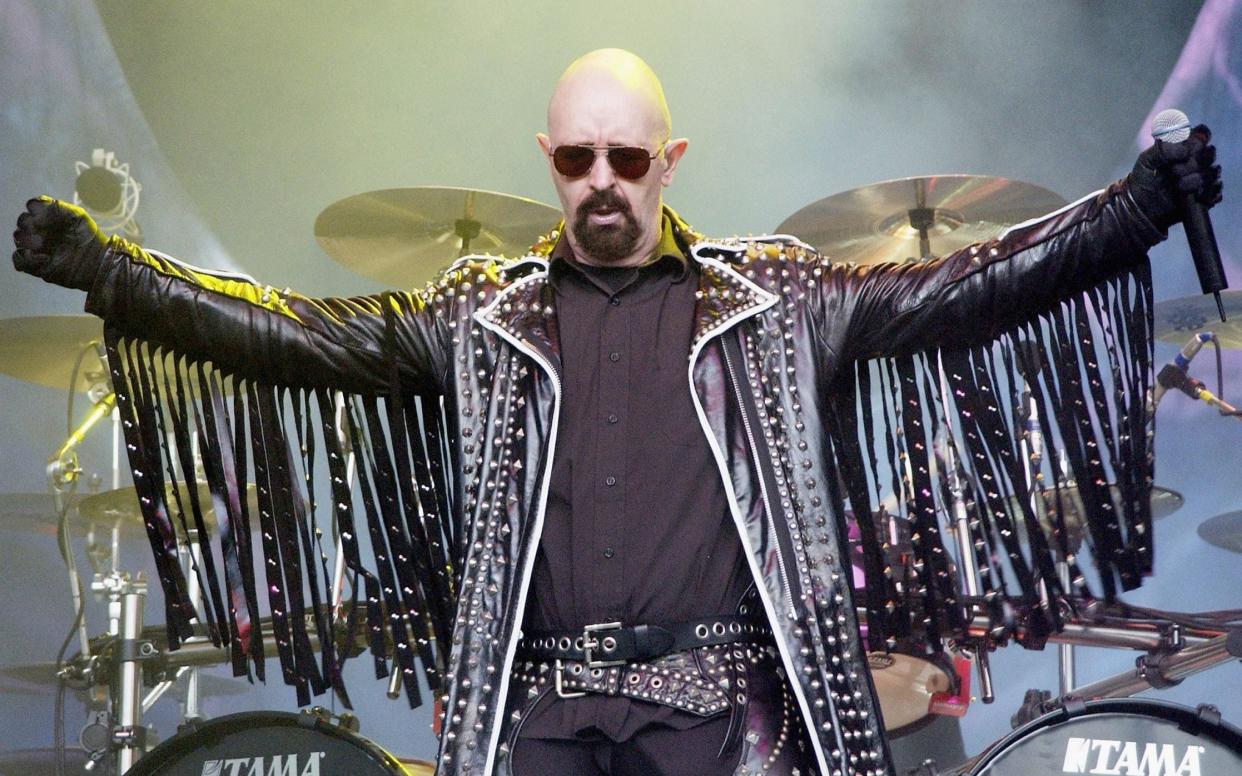

As Halford tells me this story, behind him on a bookshelf stands the compendious box set, 50 Heavy Metal Years of Music. Released this month, the exhaustive (and exhausting) collection features more than a dozen versions of the Judas Priest standard Hell Bent for Leather. It includes the song Turbo Lover, a gay anthem in all but name. An accompanying book of photographs features pictures of the singer on stage in clobber that makes the Village People look like Johnny Cash. The clues were there.

When Halford came out as a gay man, during an interview on MTV in 1998, the words were out of his mouth before he realised what had happened. “A lot of homophobia still exists in the music world, in all kinds of music,” he said, while off-screen the show’s producer dropped a clipboard in shock.

He might have added, though, that the world of metal is more tolerant than most. Aside from a few bigots writing to say they’d never again listen to Judas Priest, the singer remembers the response being supportive. “The reaction I received from the metal community made me feel really proud of who we are as metalheads,” he says. (I don’t recall anyone in the scene blinking at all.)

Rob Halford brings up this stuff because our interview falls on International Coming Out Day; I mention it because the two tribes the singer represents share a similar timeline. In the 1980s, Halford’s private life was the subject of governmental attack. Despite his group’s towering success – and in the United States, especially, Judas Priest were a very big deal – in public, he suffered brickbats from journalists who wouldn’t dream of covering other kinds of music with such unabashed hostility.

“[Judas Priest] clearly wish to present themselves as very tough boys indeed,” wrote Charles Shaar Murray in the NME, in a far from untypical review. “One presumes that rough-trade fantasies of this nature are what is necessary to counteract the titanic feelings of inadequacy that lurk just below the conscious minds of the band and their regiments of fans.”

Watching the group perform at Sheffield City Hall, the author took aim at a venue filled “with spotty youths resplendent in denim and dandruff waving peace signs… engendering the most boring and meaningless apocalypse of all.”

If Halford does harbour titanic feelings of inadequacy, it doesn’t show. Appearing on my computer screen from his home in Phoenix, the good-natured West Midlander – his accent remains – looks like Ben Kingsley cast in the role of God. Endearingly, and unusually, throughout our 45-minute interview I’m referred to by name. I’m asked what things are like back in England, and in response to the news that they’re probably much like they were when he lived here in the 1970s, the singer nods in sympathy, before telling me that his partner, Thomas, often returns from the supermarket complaining about a shortage of tortilla soup.

Given that Halford tells me “I’m 70 years old” at least five times, he is indubitably an older man. “I should be putting my feet up and watching Corrie,” he says. Yet he remains the ambassador of the most resolute metal band the world has known. At a time when members of Deep Purple and Black Sabbath looked like they were in The Grateful Dead, Judas Priest minted the genre’s on-stage aesthetic as surely as Vivienne Westwood did for punk. Much like Roxy Music and Duran Duran, they never wore denim. Without them, acts such as Iron Maiden and Slayer would not exist.

At their best, Judas Priest provide a non-negotiable rebellion with a violent virtuosic flourish. On the wholly irresistible Living After Midnight, one of the group’s few crossover hits, they blended a pop-sized chorus with metal chops and a lyric in which Halford boasts of “rocking til the dawn, loving till the morning, then I’m gone, I’m gone.” On paper, it sounds perfectly ridiculous, but I listened to it again just last night – and with the volume in my headphones cranked as loud as it would go, believe me, it was persuasive stuff.

An international army of restless youth agreed. In the cult short-form documentary Heavy Metal Parking Lot (1986), filmmakers John Heyn and Jeff Krulik filmed a selection of rowdy fans gathering for a Priest concert at the Capital Center in Landover, Maryland. Quite the rum bunch they were, too. Twenty years later, in the sequel Heavy Metal Parking Lot Alumni: Where Are They Now, the interviewees remained true to the cause. “Life changes as time goes by,” one said. “Children and dogs and a house, that kind of thing. But the heavy metal hasn’t changed… it’s something you don’t grow out of.”

As Priest raged about screaming for vengeance and breaking the law, it was obvious that the band were trading in wholesome escapism set to music that was far better than its many detractors would have had you believe. But as the quintet scored platinum disc after platinum disc in the United States, the nation’s political and religious overlords grew nervous. Alongside its noisy proclamations about being the Land of the Free, America has long harboured a tinny puritanical streak. In heavy metal, its moral arbiters found their whipping boy.

In 1990, Judas Priest were forced to defend a civil action suit in Reno, Nevada, that alleged that the group were responsible for the deaths of two fans. At the end of a day spent drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana, Raymond Belknap and James Vance shot themselves in the face with a sawn-off shotgun in a church playground in the nearby town of Sparks. Five years later, the subsequent lawsuit alleged that a subliminal message in the song Better By You, Better Than Me, from the album Stained Class, had urged the young men to “do it” (whatever “it” was).

“We were afraid,” Halford tells me. “We were afraid that if the judge did find for the prosecution, it would be like a domino effect, and not just for us. Every radio station would have to put a disclaimer on before they played anything, in case it contained a subliminal message. They would have to indemnify themselves. It was also terribly upsetting, because we were being accused of taking the lives of these two massive Priest fans. It was absolutely insane… We were fighting for everything that we had as a band.”

The suicide pact saw Raymond Belknap killed instantly, while James Vance was severely disfigured and died three years later as a result of his injuries. (“There was just tons of blood,” Vance recalled in court. “It was like the gun had grease on it.”) As part of the group’s defence, guitarist Glenn Tipton brought to court a cassette of Stained Class on which the songs were played backwards. Among the sentiments heard by the bench were “hey Ma, my chair’s broken”, “give me a peppermint” and “help me keep a job”. The case was dismissed.

In the wake of the unpleasantness, the band’s manager, Bill Curbishley, cracked a decent joke: “The only subliminal message I would put on an album would be, ‘Buy seven copies.’” In the concert film No Cure For Cancer, comedian Denis Leary aimed lower, claiming that metal fans “blowing their heads off with shotguns… [is] an unemployment solution right there. It’s the bottom of the f-----g food chain.” Never mind that the National Academy for Gifted and Talented Youth reported that its 120,000-strong student body was more likely to listen to metal than any other form of music; once again, it was fine to denigrate an entire cultural movement.

Asked whether a guilty verdict in civil court might have led to a criminal trial, for the first time in our interview Halford is lost for words. After 20 seconds of umming and aahing, he tells me, “I reckon that if the judge had found for the prosecution, then another trial would have happened as a separate sidebar. The prosecution would have said, ‘Right, proved it, you were behind the death of these guys – we’re now charging you with manslaughter.’”

Today, half a century after joining Judas Priest as an alternative to working with his father in a foundry, the music to which Halford cleaves is receiving due credit, thanks in no small part to the genre-fluidity of streaming services. But Priest made their bones, and their mark, when metal was the sound of the under-represented, and sometimes the dispossessed.

The idea that they would hurt these people is the gravest charge I can imagine. “Solidarity was always the thing with Judas Priest,” Halford tells me. “If anyone pushed back at us, we pushed back a hundred times more… You’ve really got to have that self-belief to carry on. In the early days of Priest, you had to slog to carry on. But we had that.”

They’d still be saying it now, in person, had one of them not almost died on stage last month. Appearing at the Louder Than Life Festival, in Louisville, a ruptured aorta began flooding Richie Faulkner’s chest cavity with blood during the closing seconds of the set. Prior to going under the knife for 10-and-a-half hours’ open-heart surgery at the Rudd Heart & Lung Center, four miles from the venue, the guitarist finished playing his solo without dropping a note. The song Judas Priest were performing is called Painkiller.

“That’s ironic, isn’t it?” Halford says. “Apparently there’s footage where he’s doing it, and you can see he’s struggling… I just can’t watch it. But he was still playing. Talk about metal. And now of course he has a metal heart because they replaced all of these things” – five parts of Faulkner’s chest were fitted with mechanical components – “with titanium, which lasts forever. He’s like Iron Man. He’s the Iron Man of metal guitarists. How brilliant is that?”

50 Heavy Metal Years of Music by Judas Priest is available now on Sony