Your Job Could Be Dreamy (at Least in a Painting by Lubaina Himid)

Lubaina Himid, 67, who won the Turner Prize in 2017, has been many things over her four-decade career. She has been a curator, a teacher and a cultural activist; also a theatre designer and a waitress; but always undergirding it all, she tells Esquire, as her landmark new show opens at Tate Modern in London, an artist. Born in Zanzibar, and raised by her mother in Britain following her father’s sudden death from malaria when she was four months old, professions is something that interests Himid, who was a pioneer of the Black arts movement in Britain in the 1980s and is a now professor of contemporary art at the University of Central Lancashire. One of the subjects she has often returned to in her vibrant, absorbing paintings are portrayals of men with trades (also, in other works, of women): she has painted tailors, bakers, shoemakers, dog walkers, map-makers, musicians and footballers, often in moments of intimate conversation or quiet repose. Several of these works are included in the Tate Modern show; she tells Esquire about the appeal of men at work.

Your new show at Tate Modern includes several paintings of men with jobs. Can you talk us through them?

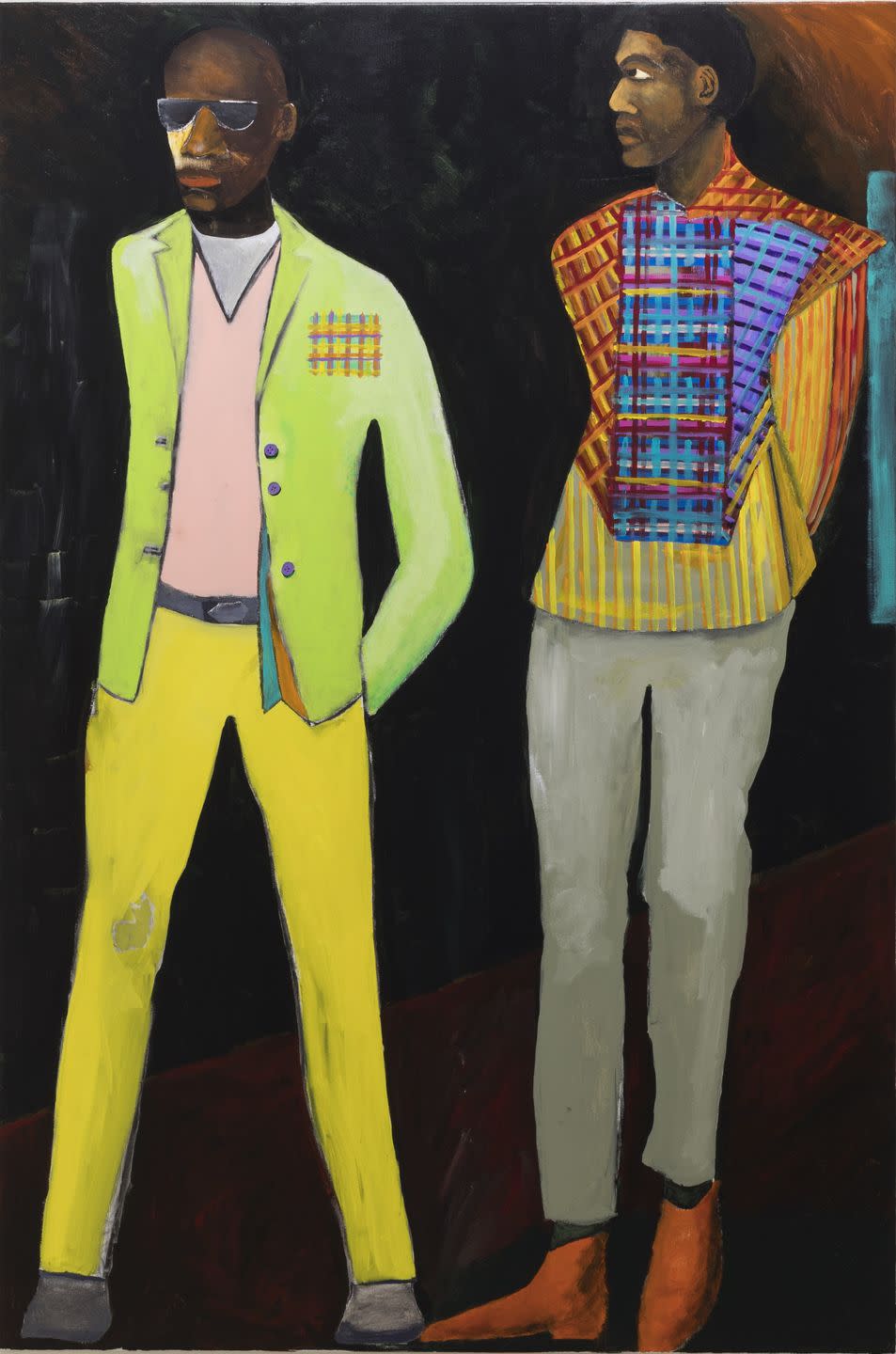

There is one painting, that I made called “Le Rodeur - The Cabin” that I painted in 2016, 2017 [see main image]. I only lived with it for fortnight after I painted it and then it was acquired by a museum, so in a strange sort of way it is one of my favourite paintings. It’s of two men, one of them is dressed as a chef, and the other one is playing an instrument, and it comes from a painting by Hogarth [“Captain Lord George Graham, 1715-47, in his Cabin”]. The Hogarth painting has a whole lot of seamen in it – a captain and his posh friends all sitting around a table – and a black musician is playing to them, and a chef is coming into the room with a chicken. I got rid of all the posh aristocrats, and just left these two men together. I’m very fond of it because it’s a Hogarth painting that I’ve messed about with, which I do quite a lot, and because I really only saw it while I was painting it and then for a very short time after. It was really lovely to see it.

Why did you swap the chicken for jelly?

I just have a real fondness for jelly moulds because they’re smooth on the outside and patterned on the inside, and so their beauty is hidden. I wanted to make a painting that was funny: that whole thought that you’ve caught a moment there where one man is playing an instrument and the other is bringing in this very delicate sweet, but they’re on a boat so anything can happen in the next 30 seconds.

What are some of the other paintings in the show that explore the “men at work” idea?

There are three particular works: one’s called “Remove From The Heat”, one’s called “Cover The Surface”, and the other’s called “Stir Until Melted (The Fortune Teller)”. All of them have two men in them. I’m imagining the end of a day, where pastry chefs have spent the entire day making the most intricate, beautiful, delicate creations, and now they’re in the back alley, outside the kitchen, and it’s, “OK, what are we going to do now? Shall we go for a drink? Shall we go to my place? Your place? Who’s in charge here?” I try to paint two men in a space where neither is the boss, neither is in control, and they’re not trying to be. I think men tend, even unconsciously, to want to be “more” something, than the other. Even if it’s more kind, or more lovely, or more a new man. But they’re always trying rather hard, in a strange way, to compete. And I’m trying to get these men to not compete, because they’ve been competing with sugar and spice and all things nice all day. And so each of them captures a moment where a decision is made between them to be equal.

Are you thinking of that idea of male hierarchy in the world, or as it has been depicted, traditionally, in art?

I think the two are the same. The history of painting is not that different from the history of the world: what’s painted in paintings is often an attempt at reflecting what’s in the world.

When did the idea of men working start to interest you as a subject?

A very long time ago. I was making a 100-piece cut-out, “Naming the Money” [in 2004], in which there were 10 dog-trainers, 10 shoemakers, 10 map-makers, all of them men. They were all life-sized painted wooden cut-outs cut to the same pattern, but each one of them is wearing different clothes, and has a different expression on their face, and is, in fact, a different man. I began then to be interested in the way that men are usually depicted. I’m always looking at great paintings and seeing what their relationships are and what the hierarchy is: who’s left out, who’s left in. This 100 piece cut-out installation was a chance to put everyone that I wanted in, who usually gets left out.

Are there particular professions you’re drawn to depicting?

I probably wouldn’t make a cut-out that was of something I really didn’t understand. There are obviously incredibly, creative and poetic things about being a lawyer, or being a banker, but I do not know that complex world of money and exchange well enough not to make assumptions. And I’m the absolute opposite of wanting to perpetuate a stereotype. I’m trying to undo stereotypes.

You’ve made a couple of works involving tailors. Why?

I’m very interested in men’s relationship to their clothes. How when they’re putting on one pair of trousers in one fabric, or another pair of trousers in another fabric, it actually makes a difference to how you stride into a room. And I’m really interested in the tailored suit: that the skill and the craft of making a bespoke suit can actually change the way a man feels about himself and the way he looks; that if his left shoulder’s not as square as the right shoulder, a suit can adjust that. I think that fine craft of tailoring and understanding a man’s body is fascinating.

Is there a relationship between those jobs and traditional fairy stories – The Elves and the Shoemaker, say, or The Town Musicians of Bremen – in which they often appear?

That’s a very interesting question actually, I’ve never made that connection before. But you’re absolutely right, perhaps when I’m imagining I am going back to those fables and old-fashioned stories, moral stories, I suppose. But I had a lot of books when I was a child with those kinds of images in them. When I think of my childhood I think of myths and legends and Grimms’ Fairy Tales and Hans Christian Andersen and the owl and the pussycat going to sea. All that.

You’ve also mentioned a story in your own family’s folklore, that you’ve referred to as “the curse of the grocer”: your father was once asked to take a grocer’s sick wife to hospital but refused and she then died.

That’s really interesting. I was four months old, so I was there but I wasn’t there, but I can see the grocer, and I can see the shop, and I can see him in the street waving my father down in his car, and him saying he didn’t have time to stop. So yes, that is very strange. Maybe it’s a painting I need to paint.

You grew up in a female-led household: did that give you particular ideas of what “men did” and what “women did”?

I suppose I knew absolutely what women did, because of my mother and my auntie and my grandmother. But men were not the enemy in my house – my mother and my auntie were great party-goers, party-givers, they went to clubs, and they always looked fabulous – so it wasn’t like there was a binary opposition. But to me men were a blurry unknown. I didn’t have any brothers and I went to a girls’ school, which of course makes men even more full of mystery, but it gave me a chance to understand myself not in relation to men. I liken it to driving a car: it’s great if you can learn to drive where there are no cars on the road, and you actually learn how to drive. But clearly, everybody thinks it’s much, much better to get in a car and go straight into traffic.

Has your idea of your own profession as an artist changed during your career?

I started out thinking that I was going to be a theatre designer, because I thought I could work in political theatre and do things that made a difference. I went to art school and I was taught about opera and ballet, and though I fell in love with the whole idea of opera, I began to understand that it really wasn’t the world for me. I worked as a waitress for a long while and started to put the work of my friends on the walls of the restaurant, and to have exhibitions; then I began to think about other black people making art but not being able to get it on the walls of galleries, and started to put that into action. But all the time I was making work myself, works on paper or cut-outs on wood, and I’d always get up in the morning and think of myself as an artist. My mother, who was a textile designer, never questioned that, and I was lucky enough to be brought up by people who, if you wanted to be an artist, that was OK. Before she died my mother knew I was having this show at Tate Modern, and she was very pleased about that. She never pressurised me into having a proper job.

It seems like it paid off.

It did.

Lubaina Himid is on from 25 November 2021 to 3 July 2022 at Tate Modern, London, tate.org.uk

You Might Also Like