Radical, potent and still very funny — Jerusalem is storming the West End

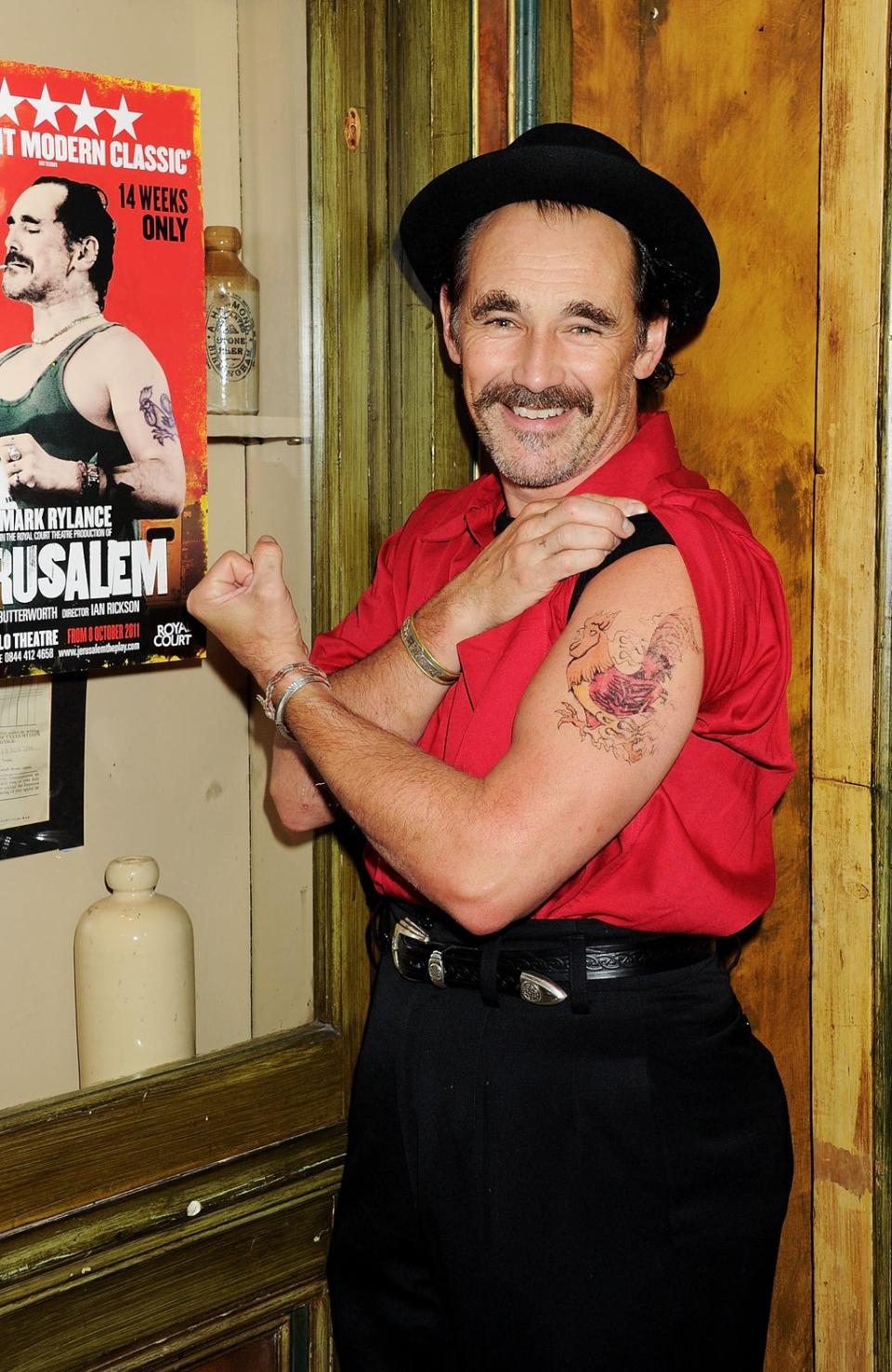

Jez Butterworth’s 2009 play Jerusalem is one of the most exciting events I’ve experienced in over three decades of writing about theatre – an instant modern classic, a galvanising exploration of Englishness, and now a political football in the culture wars. With the role of drug-dealer, daredevil, braggart and shagger Johnny “Rooster” Byron tailored to fit an on-fire Mark Rylance, it burst yowling onto the Royal Court stage, went to the West End and Broadway and won every award going (almost: it lost the Tony for Best Play to War Horse).

Hilariously funny and brilliantly anarchic, with Rooster a Lord of Misrule in the Falstaff mode to the teenage attendees at his illegal caravan parties, it also carried a dark undercurrent of sexual threat and a potent, sometimes chilling mysticism. Rooster is often described – pejoratively by those who despise him – as a ‘gypsy’ in the script, and claims for himself ancient blood and ancient rights to the land and its mysteries. Like Shakespeare’s Owen Glendower, he says he can summon giants; watching in 2009, I believed him.

Now revived again at the Apollo, with Rylance, several other cast members including Mackenzie Crook (as unemployed plasterer and would-be DJ Ginger), director Ian Rickson and most of the production team reassembled, Jerusalem is ripe for reappraisal. Is this once-radical work now a lazy commercial choice, deployed to fill seats and coffers emptied by Covid? Did Rooster’s roots in English soil and folklore predict the nativism that brought about Brexit? Was Jerusalem the last time a playwright dared to say what he felt before self-censorship stifled theatre? I think the answers to these are no, no and not really, no.

Butterworth burst onto the scene in 1995 with Mojo, written when he was 25 and mounted on the Royal Court’s main stage by Rickson. (Though I remember him at earlier Edinburgh Festivals as part of a loose Cambridge University group of writer-performers that included Alexander Armstrong and the director Crispin Whittell). A stylish, fast-talking and sexually creepy thriller set in the pilled-up music world of 1958 Soho, Mojo earned comparisons with John Osborne’s revolutionary Look Back in Anger.

A film version directed by Butterworth followed in 1997: it was slow, stagey and unremarkable apart from a chilling turn by Harold Pinter – who became one of Butterworth’s mentors - as a predatory gangster. Then came another movie, Birthday Girl (2001), featuring Nicole Kidman as a Russian mail-order bride, which he co-wrote with his brother Tom and also directed, and which was also disappointing.

It was seven years before Butterworth returned to the stage with The Night Heron in 2002, and in 2005 he moved with his then-wife and young children to rural Devon, then to Somerset, producing The Winterling (2006) and Parlour Song (2008) before Jerusalem arrived. Born in London but raised in St Albans, Butterworth had already done a stint living in Pewsey in Wiltshire with Tom when he was 25 and skint. Pewsey was his model for Flintock in Jerusalem.

He actually began work on what would become his opus in 2003, aiming for a state-of-the-nation play. “It was shit,” he told a Tortoise ThinkIn this week, “because I had an idea for a character and a setting and nothing else. That’s not even half of a play.” He regards as irrelevant every version written before Mark Rylance visited him in 2009 and recited a Ted Hughes poem. Rapt by the actor’s cadences, Butterworth bashed out a new draft of Jerusalem in a month, working on it at night while doing an uncredited polish on someone else’s film script during the day.

He wrote this version instinctively, guided by whether or not a scene or a speech gave him goosebumps. Though references to William Blake’s poem abound, he claims that any echoes of Blake’s mystical, Christian Albion are incidental. The action takes place on St George’s Day but it’s not modelled on the St George myth either. Nor is it autobiographical: though Butterworth shares his initials with Johnny Byron.

Jerusalem was reportedly rewritten extensively during rehearsals, and many of its themes reflect Rylance’s own passions and interests. I first interviewed the actor in 1990 when he quit the RSC – shortly after giving the best Hamlet I’ve ever seen – to found a touring theatre company called Phoebus Cart with his wife Claire van Kampen, to perform Shakespeare on the site of ancient ley lines. (Jerusalem features a speech about ley lines and their spiritual importance.) The next time we met was on the set of Jerusalem at the Apollo, where he was preparing a benefit evening to protect tribal culture worldwide.

“I sort of thought that at 50 you either start dying or you start living,” he said then, on taking the role of Rooster aged 49. He’d spent ten years running Shakespeare’s Globe (immersing himself in British myth, literature and music, as well as getting casts to play volleyball together), had a sideline in arthouse films, and had just played a dreamy naif in the sex comedy Boeing Boeing. He’d never done anything like Byron.

The character’s body is twisted by daredevil motorcycle stunts that went wrong, and years of pub fights and substance abuse, his butterfly mind always flitting to the next tall story. Rooster announces himself to the audience with a headstand in a water butt, before necking a pint of milk laced with a raw egg and a wrap of speed. He then roars and rabble-rouses for three straight hours.

The central impetus of Jerusalem is change: the needs of the “new estate” prompting Kennet and Avon Council finally to evict Rooster and destroy his caravan; the character of Lee, who’s burned all his Smurf figurines before heading to Australia; the chaos of puberty and the possibility of predators who will exploit it. It’s my view that Butterworth was writing from his own experience of change and stasis, and in the process that he actually did write a state of the nation play.

In the mid to late 90s playwrights like Butterworth and Martin McDonagh were feted like rock stars. A year after Mojo appeared, journalist Stryker Maguire wrote the article ‘London Rules’ in Newsweek which is largely thought to have heralded the whole concept of Cool Britannia. Film, music and theatre were thriving and in 1997 John Major’s moribund government fell to Tony Blair’s shiny New Labour.

The 90s and early 2000s in London were a time of creative confidence but also huge excess and cultivated hedonism. Butterworth was in the middle of it – specifically, suddenly, in the slippery world of film - but bearing the imprint of his past. His family’s home in St Albans was a blokey one, but also one where the four brothers and one sister were aware of but unable to speak of the wartime trauma that scarred their loving father (he took part in the Omaha landings). Butterworth knew about rustic ennui and end-of-week hedonism: he knew what it was like to be skint in Pewsey.

When he wrote Jerusalem in the dark of his Somerset fastness, for the London elite he’d joined, he was in part writing about a left-behind rural and regional class. So far, so Brexit-y. But it’s an impossible stretch to equate the play’s exuberant, animist celebration of Englishness with the mean-minded flag-shaggers of the present day. (Butterworth told Tortoise last week that he was disgusted by the current government’s leader and policies.)

He was also writing about what it is like to be both a teenager and a young father (Johnny Byron has a young, troubled son, Marky, in the play). What it’s like when the height of your ambition is to be pissed on cheap booze and high on cheap speed. And the realities of life and death: he kept and killed geese and ducks on his farm, and took pigs and sheep to an abattoir. Jerusalem features an enthusiastic slaughterman, Davey, one of the few characters happy with his lot. It’s also a play about community and inclusion. Rooster’s idea of Englishness is a party open to all.

Would it be written differently, or at all, today? We’ll have to see if rehearsal rewrites on this revival have bolstered the roles of the three funny but functional teenage girl characters, one of whom, Phaedra, may have been abused by her stepfather. But the idea, voiced in some sections of the media, that you couldn’t write a character as morally dubious but enthralling as Johnny Byron today, or that writers are now too cowed to write with ambition about contentious subjects, is ludicrous. Think of the plays of Anya Reiss, Mike Bartlett, Lucy Kirkwood and James Graham.

What Jerusalem did re-establish, though, was the idea of the play as phenomenon, the cultural must-see. Part of it was Rylance and the rest of the cast (the contributions of Crook, Tom Burke and Danny Kirrane first time round can’t be underestimated). Part of it was Rickson’s production and ULTZ’s bucolic-alcoholic design milieu. But a lot of it was in the writing. I can think of many sensations since – Hamilton, War Horse, Harry Potter – but the only ones that aren’t musicals or trading on established properties are Lucy Prebble’s Enron and Bartlett’s King Charles III. And both of them have a cool cleverness compared to Jerusalem’s full-blooded, full-throated riotousness.

Of course producer Sonia Friedman’s 16-week revival is exclusionary to a degree. Almost totally sold out the moment it was announced, with many tickets priced at £150, it would be geographically and financially out of reach to its own characters. That doesn’t mean Jerusalem shouldn’t be revived this way. Post-Covid, anything that rejuvenates the mixed ecology of theatre is welcome. And far from atrophying into a ‘safe’ commercial choice, I expect the play to yield new riches 13 years on. The disenfranchisement it speaks to hasn’t gone away. Nor has the debate about what England is, and who it is for. And the desire to congregate, to have a good time and be transported – whether by Rooster Byron or by Jez Butterworth – is stronger than ever.