Invisible deaths: from nursing homes to prisons, the coronavirus toll is out of sight – and out of mind?

John Delano was six years old when the contagion struck his neighborhood in New Haven, Connecticut. There was a morgue just down the road. Coffins began spilling on to the sidewalk. It made the perfect stage for an exciting new game.

“We thought, ‘Boy, this is great,’” he recalled. “‘It’s like climbing the pyramids.’ Then one day, I slipped and broke my nose on one of the coffins. My mother was very upset. She said, didn’t I realize there were people in those boxes who had died?”

Related: Faced with an appalling US coronavirus death toll, the right denies the figures

Delano’s account, recorded in Catharine Arnold’s history of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, encapsulates a crucial aspect of that disaster: the public nature of death. Coffins became a feature of daily life, stacked on sidewalks and in people’s front rooms. Roads were jammed dawn to dusk with horse-drawn hearses, heading for the cemeteries.

A century on, death has disappeared from the streets of America. The 2020 pandemic is memorable not for coffins piled high but for data modeling and statistics. For most Americans, the figure of 85,901 deaths in the US is as visceral as it gets.

A virus that is in itself invisible has spawned a nationwide response in which the most extreme manifestation of the disease, loss of life, is invisible too. You can’t play coffin pyramids when funerals have been transferred to that great resting place in the cyber-sky: Zoom.

“We hear and talk about death all the time but we are not seeing anything,” said Megan Devine, a psychotherapist and grief educator in Portland, Oregon. “We know the statistics but are we letting that number, the weight of all that lost humanity, in?”

In the absence of the physical rituals associated with grieving, Devine said, even loved ones who succumb become invisible. “You can’t be at their bedside when they are dying, you can’t go to their funeral or viewing. They just vanish. That deepens the unreality of death.”

We hear and talk about death all the time, but we are not seeing anything

Megan Devine

In any national or global emergency, the media play an outsized role in conveying extreme experiences to those who have no direct contact. The image of Kim Phuc, the “napalm girl” in the Vietnam war, became the recognised representation of the conflict, energising the peace movement.

Covid-19 has yet to be framed by such an image. Photographers have struggled to fill in the void, as they are hampered on several levels.

Privacy laws make access to hospitals extremely difficult. Photographers have been hit by the dearth of protective gear which they need to guard their own health, a problem compounded by the fears of news organizations hesitant to take on liability were their employees to fall sick or die.

One of the many surreal aspects of coronavirus in the US is that photographers are surrounded by one of the biggest rolling news stories of their lifetimes, yet are being forced to sit idle. The National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) recently held a fundraising drive for freelancers whose work has dried up.

If ordinary citizens don’t see it, then they start to think, 'This is not my problem, it’s other people’s problem'

Ralph Begleiter

“The power of the image is connecting people to other people’s humanity,” said Akili Ramsess, NPPA executive director. “But getting to those images is becoming increasingly hard, and it’s what we’re missing with coronavirus.”

Rosem Morton understands better than most the gulf of invisibility between reality and media depiction. She wears two hats – she is a nurse working in operating rooms as well as a professional photographer.

Morton said the combination of privacy laws, censorship by healthcare institutions, liability fears and PPE shortages has meant that news outlets are only transmitting to the public a sliver of the intensity of the disaster at hand.

“There are many sides of this story that we do not get to see,” she said, “and the images that reach the public are very limited.”

At worst, Morton thinks the relative paucity of media images is contributing to widespread disengagement. “People are not taking safety guidelines seriously for themselves and for others,” she said.

Ralph Begleiter, a former CNN diplomatic correspondent and University of Delaware journalism professor, has firsthand experience of the importance of media visuals in counteracting the invisibility of death. In 2005, he played a central role in persuading the Pentagon, under threat of legal action, to release photographs of US soldiers returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in flag-draped military caskets.

“I think those images did make a difference. Americans were not seeing them,” he said.

There have been a number of searing images that have emerged from the Covid-19 crisis, such as the haunting pictures of refrigerated trucks parked outside hospitals, waiting for body bags. Another memorable shot was of mass graves being dug on New York’s Hart Island – the New York police department swiftly confiscated the drone used to snatch it.

But Begleiter fears that most of these powerful photos have come from virus-stricken urban centers – New York, Washington, Chicago, Seattle – as opposed to the rural heartlands now feeling the brunt of the pandemic.

“If ordinary citizens don’t see it in their everyday lives, then they start to think, ‘This is not my problem, it’s other people’s problem’ – and that’s what’s happening now in rural America”, he said.

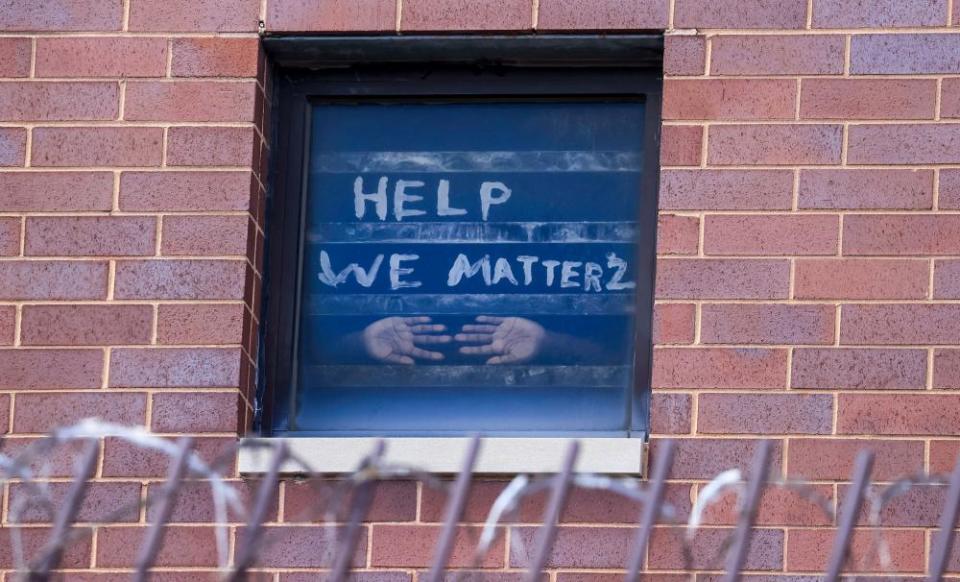

The invisibility of the crisis in the US heartlands is aggravated by the concentration of deaths in locations far away from the lived experience of most Americans. Hospitals aside, the full hurricane blast of the pandemic is being felt in three places, all of which are largely or totally out of bounds to the public: nursing homes, prisons which have a high proportion of African American inmates, and meatpacking plants that employ largely migrant Latino workforces.

The segregation of Covid deaths out of town and behind locked doors, where most Americans cannot see them, has provided a political boon for Donald Trump. It has allowed the president to downplay the significance of the virus for weeks on end, pushing for the reopening of the economy even though it risks the lives of tens of thousands of largely poor and black and Latino citizens.

That phenomenon was on full display this week when Trump scolded his top infectious diseases official, Dr Anthony Fauci, for saying opening up the country could risk a spike of new infections. Trump said of Fauci’s science-based, factual remark: “To me, it’s not an acceptable answer” – a claim he could never have got away with had the human costs of Covid-19 been more visible.

The detachment many Americans feel has also allowed Trump to play the “other” card, depicting the contagion as the fault and property of other people. He has tried to pass the virus off as a foreign problem – the “China virus” – while blaming Democratic governors merely because their states happen to contain the most-stricken cities.

Scapegoating has been a feature of pandemics through history. Jews were blamed for the Black Death of the 14th century; conspiracy theories erupted in the first world war, that Germany had created the Spanish flu as a bioweapon; during the 2003 Sars epidemic, Asian American communities faced stigmatization and discrimination.

“Every pandemic I’ve looked at has seen a rise of racism,” said Steven Taylor, a clinical psychologist at the University of British Columbia in Canada.

Taylor has launched a study of 7,000 representative adults from the US and Canada to gauge how they are coping. His early findings suggest that the invisible nature of the harm inflicted by Covid-19 is provoking volatile behavior at opposite ends of the spectrum.

At one extreme, about 15% of those surveyed were found to be suffering from what Taylor has dubbed “Covid stress syndrome”. These people are so hyper-aware about the contagion, even though they cannot see it, that they experience profound anxiety about coming into contact with it, to the extent of becoming virtually housebound.

At the other extreme, a similar-sized subset have drunk Trump’s Kool-Aid and are convinced that the scourge is a hoax or overblown.

“They are coming out and saying, ‘We can see the economic devastation of the lockdown all around us, but we can’t see people who are sick and dying,’” Taylor said.

The wave of lockdown demonstrations outside state capitolsis the sharpest manifestation yet of this. At its most dystopian, it has stoked a new generation of conspiracy theories such as Plandemic, a misinformation video which has attracted millions of viewers online by falsely claiming coronavirus is the creation of drug companies and Bill Gates.

With the scramble to find a vaccine for Covid-19 still months if not years away from success, Taylor has some alarming news about the prevalence of anti-vaccination sentiment. In a fresh sampling of his survey group which has yet to be published, he found that a startling 21% of Americans said they would refuse a coronavirus vaccine.

Were that proportion to translate into actual vaccine rejection, it could jeopardize the herd immunity upon which the health and safety of all Americans will depend.