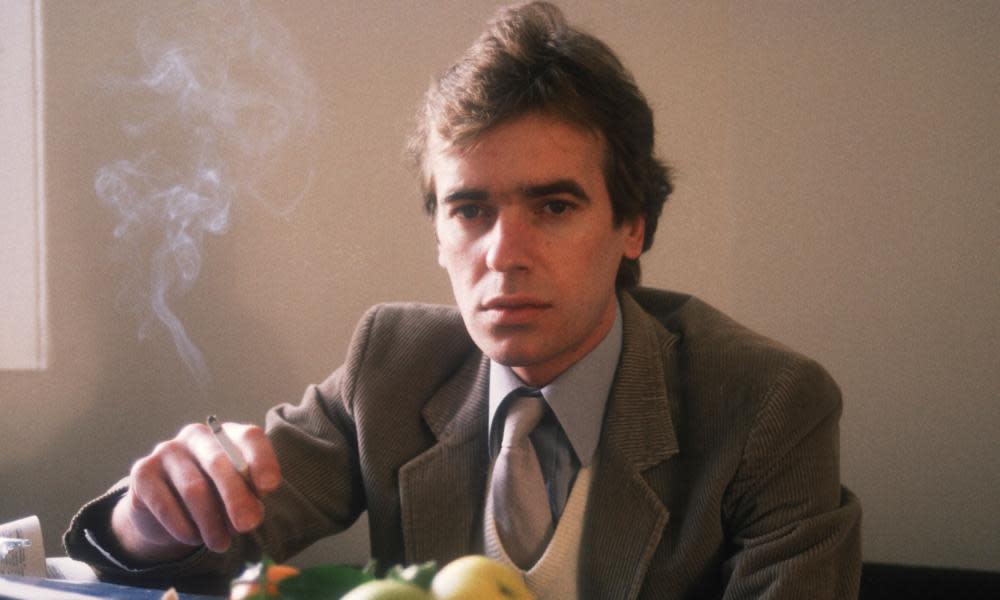

Inside Story by Martin Amis review – a curious mashup of fiction and memoir

Inside Story is a deeply curious book, in both senses; it asks a lot of questions, and it often asks them oddly. It’s a second go, for a start: a partial autobiography that describes itself as a novel and which is built on the ruins of an abandoned project of a decade or more ago, a book called “Life” that died a death before it could see the light of day. It is a true story that clearly takes liberties – recasting historic conversations so that they read as little playscripts, slipping between real names and pseudonyms, darting back and forth in time. And, of course, there has already been a memoir, 2000’s Experience, which focused more directly on Amis’s parents, Kingsley and Hilly.

Related: Martin Amis: 'I was horrified that Trump got in. Now it’s looking scary'

But Inside Story’s chief strangeness is that we know a great deal of it already, because years ago Amis seemed to become a character in a novel others were writing about him, elevating him to an almost archetypal status while complaining bitterly about all the attention he got. The novel was added to and subtracted from, but ongoing themes included Dad, Dentistry, Money, Women, Height. This is, perhaps, Amis taking back the manuscript of this continually evolving narrative which is, after all, his.

The book articulates the enormity of raw grief with arresting bravery, as Amis details the illness and death of his best friend, Christopher Hitchens, and the loss of his next best friend, and mentor, Saul Bellow, to Alzheimer’s disease. He apprehends both men as gigantic forces of nature and intellect and himself as the chronicler of their decline and separation from the world. Each episode prickles with tragicomic particularity: Hitch, enduring an experimental treatment for oesophageal cancer, throwing up in a hospital flowerbed as he snatches a fag break; Bellow sitting silently throughout a public discussion of Conrad’s The Shadow-Line, speaking only once, in answer to the question “What’s Augie March about?” “ And Saul said, ‘It’s about two hundred pages too long.’” (The same is true of Inside Story.)

Inside Story is odd and sad and funny, sometimes a bit too fond of itself, utterly compelling on grief

One inadequate reparation for bereavement is the literature of loss, in these pages exemplified by two poems: Philip Larkin’s “Aubade” (“Death is no different whined at than withstood”, though Amis takes some trouble to illustrate how much more whining Larkin did than withstanding); and Wilfred Owen’s “Strange Meeting”, with its mention of “the undone years” – not merely the life that the deceased will not experience, but that which the survivor will. Inside Story is, in this context, a piece of survivor literature, with all the ensuing guilt, sorrow and confusion – and also the undeniable relief at continued existence.

Not that you’d always know it. Amis is, as expected, lavishly grumpy about getting older. He hauls himself to a literary festival in St Malo at which it is his wife, Isabel Fonseca (“Elena” throughout the book), who is being feted. There he plonks his book France and the Nazis on the cafe table (he’s also packed histories of the rape of Nanking, the battle of Verdun and the Rwandan genocide) and idly wonders why everyone he knows – including his three-year-old daughter – doesn’t kill themselves. He worries that Elena will be subjected to antisemitism and anti-Americanism while in France – it is March 2003, and the days leading up to the bombing of Baghdad. He also clocks that an American mystery writer, whom he names, in typical Amis fashion, “Jed Slot”, is being inundated with interview requests, while he is not; and that most of the French writers look thoroughly miserable. “I noticed that one no doubt much-praised sourpuss (his baldy haircut, his nicotine-rich moustache, his mouth like a half-empty goody bag with its lumps of fudge and butterscotch) was warmly berating the meek little blonde at his side, who sat with her hands clenched and her head contritely bowed. Come on, darling, I thought (as I secured yet another glass of white wine), heed Moses Herzog. ‘Ladies, throw out these gloomy bastards!’”

What Amis means by gloomy is, perhaps, humourless, and it is clear that he regards humour as an essential part of sane, civilised humanity. He castigates Samuel Richardson, author of Clarissa, for lacking it, and praises Henry Fielding, especially in Tom Jones, for deploying it; it is what he loves about Hitchens’s political brain, and deplores the absence of in Jeremy Corbyn’s. It is what, he explains, distinguishes the work of the apparently gloomy Larkin, whom he calls “by many magnitudes the funniest poet in English”.

But he also recognises that for a sense of humour to find its most effective expression it must catch the right tone. And in terms of tone, Inside Story is – flamboyantly, provocatively and surely deliberately – all over the place. The laments for the dead and dying are not so difficult to catch; there is a sort of tacit agreement that we all know that grief must encompass the sublime and the ridiculous if it is to have any meaning. The almost-novella that dominates the book’s first half and more, the story of the twentysomething Amis’s sexual obsession with a woman named Phoebe Phelps is, however, a gauntlet thrown down to the reader, being yet another foray into the problematic world of the Big Male Writer. We are back in the world of London Fields and Nicola Six, The Pregnant Widow’s Gloria Prettyman and all the rest of the female characters who have functioned, through the decades, as tantalisers, teases, withholders, dangerous shape-shifters and, in this case, “tits on a wand”.

Here, look at this, says Amis: here I am, joyously objectifying this oddball beauty who is, essentially, stringing me along with her perfect body, capricious appetites and mysterious self-sufficiency. Think again, because now she is a little girl, sexually abused by the family priest, pimped by her father, emotionally abandoned by her mother. Now she is a porn model, an escort, a madam in a business suit. And here she is again, older, weirder, telling me that my mum had an affair with Larkin and that quite probably my dad is actually the Hermit from Hull, which means, even more horribly, that my granddad is Sydney Larkin, an out-and-out Nazi. Which is pretty bad, because I, Martin, really, really hate Nazis.

All the paternity nonsense functions in a funny way as a sort of tonal bridge between the Withnailish capers of youthful Mart and the Hitch in Soho (Mornings in the pub, grappa after lunch; how did the New Statesman ever get published when they were on staff? The dutiful, tidy-desked Julian Barnes, one supposes) and the losses of later life. It’s a reminder that Amis’s life is extravagantly peopled, for someone who sits at his desk for much of the time. And this is before we get on to Iris Murdoch, stepmother Elizabeth Jane Howard, much more about Kingsley and Hilly; and then Trump, and all the countries that, impishly, Amis decides to cast as characters in his geopolitical musings, Israel and America chief among them (“If Israel were a person, what kind of person would Israel be? Well, male, anyway – male, for a start”).

I understood the Phoebe Phelps material better when I remembered Somerset Maugham’s short story “The Luncheon”, and wondered if Amis had also recalled it. In it, an impoverished young writer is semi-tricked into buying a ruinously expensive lunch in Paris for a female fan who, while telling him she eats nothing, orders delicacy after delicacy. Years later, he has his revenge when he sees her at the theatre and she is grossly obese. It is a quite horrible story, and makes me hope that Maugham is being fleeced and squished by fat women in the afterlife (unless he’d enjoy it too much). Phoebe Phelps, to me, is Amis in full disgraceful mode, courting our disapproval.

Related: Martin Amis novels – ranked!

But hold hard, because there is yet another strand, in which Amis dips out of whatever narrative he is spinning to dispense writerly advice to his younger self. If these sections are intended to be parodic, I liked them very much; they were silly and funny and admirably self-mocking. If not, I might want to know more than how to use who and whom, and that literary modernism began in 1922. I feel entitled, in other words, to a little more expertise.

What is the final verdict, then? Inside Story is odd and sad and funny, sometimes a bit too fond of itself, utterly compelling on grief. It also contains a moment of what one might call vintage Amis, which occurs as the writer turns on the TV to watch the unfolding horror of 9/11. At the same time, he “activated the kettle”. It’s a tiny dollop of bathetic overwriting: while, oceans away, men are hijacking technology to kill thousands, Martin is helplessly making a cuppa. But still, one thinks: mate, nobody activates the kettle. It’s fine just to put it on. Although even as I write that, I imagine Hitch rolling his eyes and saying to his friend, “Oh, man: chicks.”

• Inside Story is published by Vintage. To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.