Illustrating the World: how Dürer turned woodcutting into great, bloodthirsty art

Surely, Illustrating the World, a new exhibition of 16th-century woodcuts at the Holburne Museum in Bath (better known these days as Lady Danbury’s house in the Netflix series Bridgerton), was bound to be a dusty, bookworm-ish affair. Yet, inside the ballroom, opposite a cabinet of Imari ware, there’s a brutal portrayal of the martyrdom of St Simon the Zealot, in which, tethered upside-down and naked to a wooden frame, he’s sawn in two like a carcass in a slaughterhouse. Um, shouldn’t there be a trigger warning?

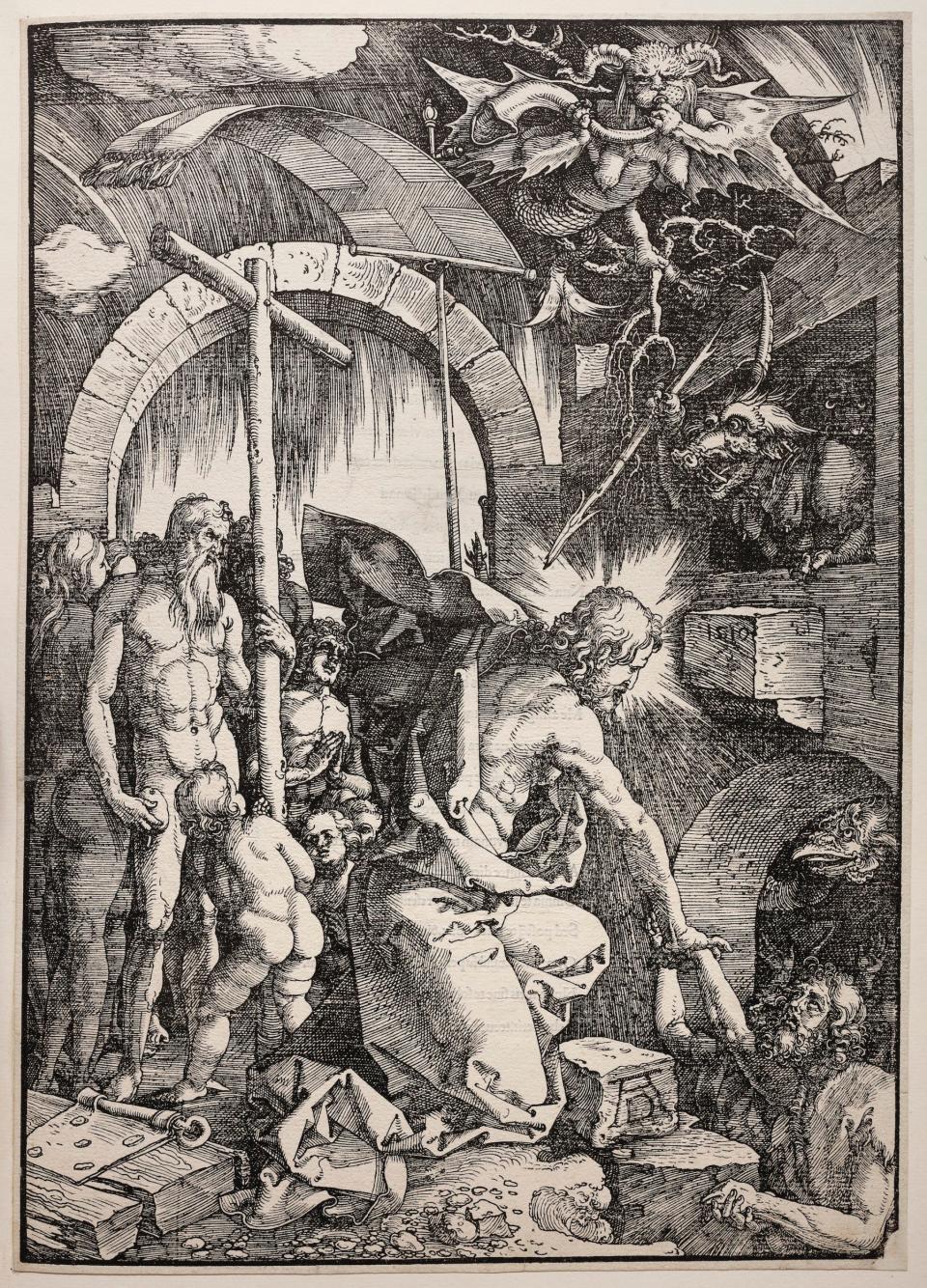

On reflection, it’s hardly more horrifying than the imagery gathered for the exhibition’s main event in a chapel-like gallery upstairs – where a complete set of 12 prints known as the “Great Passion” is on display. Created by the sublimely talented (and self-regarding) German Renaissance polymath Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), the suite depicts the agonising final hours (and resurrection) of Jesus Christ. Yes, it’s the familiar narrative at the heart of Christianity, but it’s still a shock to be reminded of its violence.

This is a fascinating, focused exhibition that fully contextualises a famous cycle of Western religious art, in which Dürer exploited and extended the revolution in communication brought about by the invention of the printing press. The Great Passion – so-called because of the impressive size of its single-leaf woodcut illustrations – was published as a book in 1511, although Dürer had created most of its images earlier, during the 1490s, following an apprenticeship in the workshop that produced the encyclopaedic Nuremberg Chronicle (a copy of which is also on display in the ballroom).

Each of Dürer’s woodcuts is dense with dynamic details. Look out for the little Löwchen dog, his back shaved, scampering about more than once in the foreground, as well as a Big Bird-like demon peeking around an arch in The Harrowing of Hell. The crown of thorns appears especially malevolent, like a coiled, spiny worm. In Dürer’s Crucifixion, angels bearing chalices collect blood spouting from His wounds like lachrymose barmaids pulling pints.

The most remarkable thing, though, is how radically Dürer’s approach changed following his second trip to Italy, in 1505-07. After he’d encountered Italian Renaissance art at first hand, his images – which once had a Gothic feel (vertical, flat, choked with details like thistles overgrowing a garden) – became more harmonious and lucid, with a greater sense of depth.

In either mode, his woodcuts’ subtle precision remains astonishing – especially when compared with the comparatively rudimentary efforts in the ballroom, where several more books, produced between 1493 and 1572, are on show. Like our own, their era was one of convulsion and pestilence and religious fanaticism – hence, presumably, that bloodthirsty sensibility. On this evidence, though, Dürer turned a scrappy, workaday medium into something worthy of great art.

Someone else at the Holburne considering atrocity is the Barbadian-born contemporary artist Alberta Whittle, whose latest exhibition – Dipping below a waxing moon, the dance claims us for release – responding, in part, to an 18th-century plantation daybook in the museum’s collection, opens on Friday. Inside a gallery, Whittle presents a group of seven new sculptures: figures wearing sequinned masks and shaggy raffia costumes reminiscent of those donned during Caribbean carnival, all performing the limbo.

Except this limbo is often impossibly low. One or two of Whittle’s dancers are even slumped on the floor like hay bales, or victims upon a scaffold awaiting the guillotine – although their outfits, adorned with bells, cowrie shells, and beads, give their apparition-like forms a joyous, festive aspect.

To the difficult subject of slavery, then, Whittle brings a surprisingly uplifting sense of whimsy, as she seeks to, as she puts it, breathe “life force” into those nameless multitudes who’ve been forgotten.

Dürer until April 23, Whittle until May 8; holburne.org