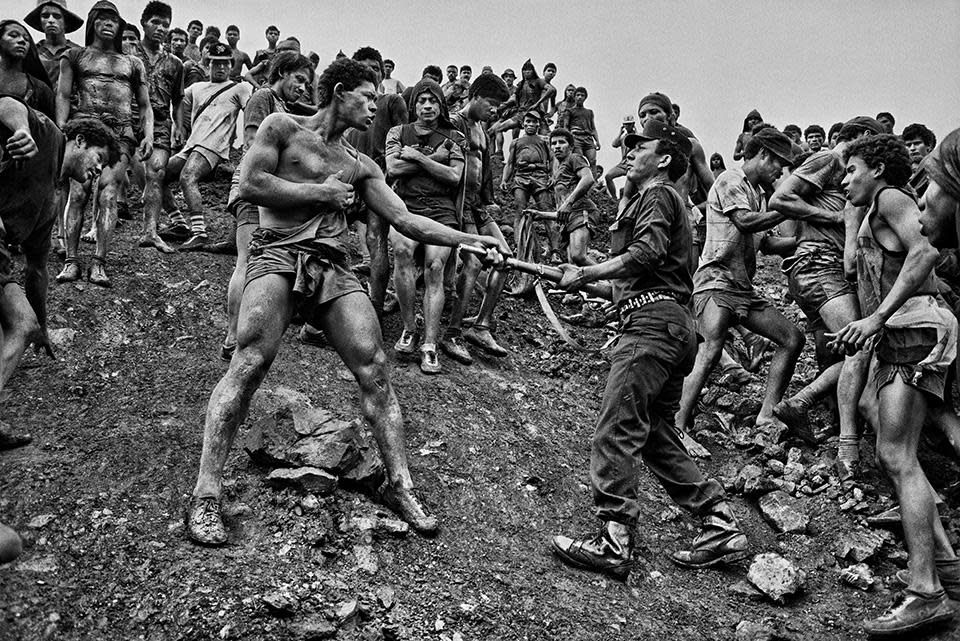

Haunting black and white images of the Brazilian gold rush by Sebastião Salgado

When Sebastião Salgado was finally authorised to visit Serra Pelada in September 1986, having been blocked for six years by Brazil’s military authorities, he was ill-prepared to take in the extraordinary spectacle that awaited him on this remote hilltop on the edge of the Amazon rainforest.

Before him opened a vast hole, some 200 meters wide and deep, teeming with tens of thousands of barely-clothed men. Half of them carried sacks weighing up to 40kg up wooden ladders, the others leaping down muddy slopes back into the cavernous maw. Their bodies and faces were the colour of ochre, stained by the iron ore in the earth they had excavated.

After gold was discovered in one of its streams in 1979, Serra Pelada evoked the long-promised El Dorado as the world’s largest open-air gold mine, employing some 50,000 diggers in appalling conditions. Today, Brazil’s wildest gold rush is merely the stuff of legend, kept alive by a few happy memories, many pained regrets – and Sebastião Salgado’s photographs.

Colour dominated the glossy pages of magazines when Salgado shot these images. Black and white was a risky path, but the Serra Pelada portfolio would mark a return to the grace of monochrome photography, following a tradition whose masters, from Edward Weston and Brassaï to Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, had defined in the early and mid-20th century.

When Salgado’s images reached the New York Times Magazine, something extraordinary happened: there was complete silence. “In my entire career at the New York Times,” recalled photo editor Peter Howe, “I never saw editors react to any set of pictures as they did to Serra Pelada.”

Read more

Trailblazing images of early 20th-century working conditions

The mine at Serra Pelada has been long closed, yet the intense drama of the gold rush leaps out of these images.

You can purchase Sebastião Salgado’s Gold here

Read more

Read more Trailblazing images of early 20th-century working conditions