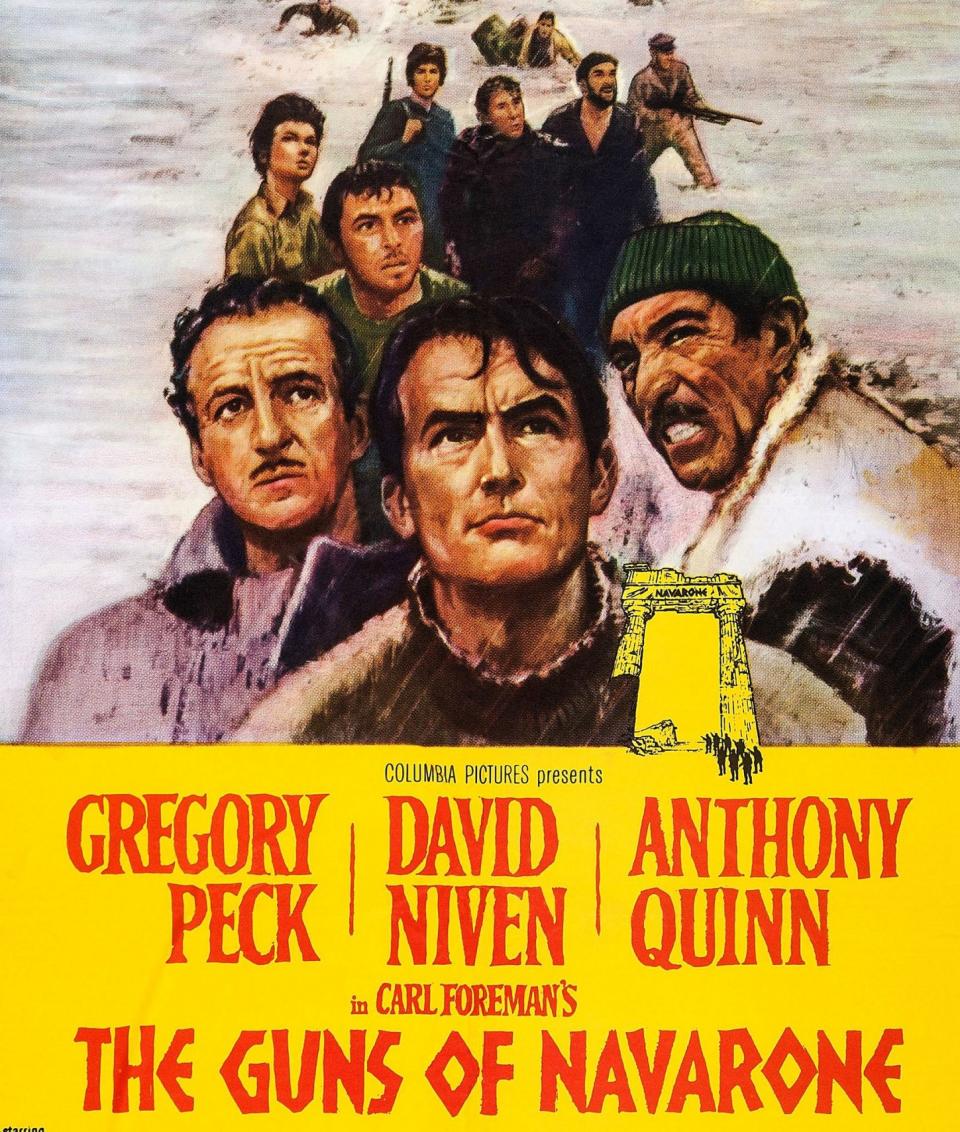

The Guns of Navarone: how David Niven’s epic blew up the war movie

Just days before The Guns of Navarone was set to complete filming, David Niven was rushed to hospital in the early hours of the morning. Niven would lie in Guy’s Hospital in a critical condition, struck down by septicaemia. These were, as Niven wrote in his memoir, “the grim times before antibiotics”.

The film’s ensemble cast – Niven, Gregory Peck, Anthony Quinn, Stanley Baker, James Darren, and Anthony Quayle – had already been through a war of sorts, part of their mission to capture a wet, wild action sequence: battling against a hellacious storm and being shipwrecked on the rocks of Navarone.

Sixty years later, the spectacle still blows any Marvel-made CGI smackdown out of the water. Peck wasn’t joking when he said: “The Guns of Navarone, I promise you, is probably the most exciting film you will ever see.” Writer-producer Carl Foreman remarked that the actors “earned their money” filming the sequence.

At Shepperton Studios – on a replica caique (a traditional Greek fishing boat) raised up on hydraulics, in a 200 x 200 ft tank filled with 6,000 gallons of water – they were bashed about and blasted from all directions. Hoses shot water into aeroplane engines, which shot the water back out at the actors, while tanks dumped more water from above and wind machines hammered them.

“There is no faking where the storms are concerned,” said Foreman. James Darren got washed away and recalled Niven clinging to a barrel. Niven gave him a gentlemanly wave as he passed.

Peck, who just a few years before had played Captain Ahab in Moby Dick, was swept overboard and sucked under the boat. He avoided being crushed only because the hydraulics weren’t operating. Niven was also dragged under and his coat got caught in the machinery. A Cosmopolitan report at the time described the carnage: “Peck sustained a three-inch gash on his forehead; Quinn and Niven twisted their spines; Baker wrenched his neck; and Darren was completely knocked out by a wave, and almost drowned.”

It was in another scene that Niven picked up the near-fatal infection: setting up explosives to destroy the eponymous guns, while up to his waist in dirty water. He got the infection via a cut on his lip. Director J. Lee Thompson later claimed that the film was close to shutting down completely when Niven was taken to hospital. “We had to decide whether to abandon the film – because we still had some important scenes to do with him – and take the insurance,” said Thompson in 2000.

A studio executive – whom Niven called the “Big Brass” – rushed in for emergency talks. “Wadda we do if the sonofabitch dies?” said the Big Brass. Niven responded: “The sonofabitch, pumped full of drugs, went back to work against the doctor’s orders far sooner than was prudent, completed the crucial three days’ work and suffered a relapse that lasted seven weeks. The Big Brass never even sent me a grape.”

Indeed, Niven rose from his almost-deathbed to complete the mission that was The Guns of Navarone. The film (now re-released on an all-new 4K anniversary Blu-ray) was a nomination-grabbing success: a film that made ensemble WW2 epics the blockbusters of their day, and remains one of the great Hollywood exercises in extreme male bonding.

According to Steven J. Rubin, film historian and author of Combat Films, films about the Second World War became a “hot Hollywood commodity” from 1949. Rubin credits several films with beginning their popularity: Twelve O’Clock High, also starring Peck; Battleground, about the siege of Bastogne; and the John Wayne-starring Sands of Iwo Jima – all released in 1949.

It wasn’t all tally-ho, action-packed war. Films in the Forties and Fifties mediated the anxieties of WW2 through drama and comedy too. The cycle of big, epic WW2 films began with The Bridge on the River Kwai in 1957 – as much about human drama as spectacle – which was followed by The Guns of Navarone, The Longest Day and The Great Escape.

“It coincided with the advent of television,” says Rubin. “Studios were fighting for a larger viewership because they were surrendering audiences to television. The only way they could figure it out was to present event films – what we now call tent pole films. I think the word that became commonplace when describing these movies was ‘mammoth’. Every WW2 epic in that era was a ‘mammoth adventure’. I don’t think I’d heard the word before in those terms. In my youth a mammoth was an old elephant!”

Carl Foreman played a prominent role in the war epic. He wrote The Bridge on the River Kwai but went uncredited – he was blacklisted after Hollywood’s anti-communist hearings. Relocating to England, Foreman was offered The Guns of Navarone by Columbia boss Mike Frankovich. The studio wanted to repeat the Oscar-winning success of The Bridge on the River Kwai.

Foreman wasn’t interested at first. The story looked like a surface-level action adventure. Foreman wanted more from his war epics. “I’m incapable of making a movie that doesn’t make statements,” Foreman later said. After re-reading it, he saw the potential for something deeper. “Although a war film, it was basically one which concerned man’s nobility in rising to the impossible,” said Foreman. His words chime with an opening speech by James Robertson Justice, the commodore who sends Peck and Co on their mission to Navarone.

Foreman said something similar when interviewed by Rubin. “He was a big anti-war advocate,” says Rubin. “His style of writing was ‘there’s no glory in warfare’. I remember him saying to me, ‘This is not a story about gods and demigods but about ordinary people.’ I think what he was trying to say is that war makes ordinary people do extraordinary acts. I think he was fascinated in how people rise to the occasion in a wartime situation, how civilians become successful fighters.”

The original Guns of Navarone novel, by Scottish writer Alistair MacLean, was published in 1957. It's fiction, but based within the real Dodecanese Campaign – the Allies’ 1943 attempt to reclaim the islands. In the story, more than 1,000 British troops are stranded on one of the islands. Rescue ships are unable to reach the Aegean Sea because of radar-controlled German cannons on the nearby (fictional) island of Navarone.

A team of specialists – including a mountain climber, explosives expert, and knife-fighting engineer – are assembled for a seemingly impossible mission: to scale the cliffs of Navarone, infiltrate the German forces, and blow up the guns. The guns are reportedly based on real guns that were based on the island of Leros, but the guns in the movie are much bigger – 80ft long and 15 tons each.

As detailed by Brian Hannan in his book on the film, MacLean’s novel was one of several from British books snapped up by Columbia – part of a drive to make more films in Britain and take advantage of the Eudy Levy tax break.

But the film needed US stars. As Brian Hannan wrote: “Americans did not like British war movies. They never had. No matter how well British war movies did on home soil, they just did not survive the journey across the Atlantic.” Potential stars included Cary Grant, William Holden, and Dean Martin. Carl Foreman scored huge publicity for the film by casting opera singer Maria Callas – and got yet more publicity when Callas quit the production.

The original novel was all-male, but Foreman changed two of the characters into women – two Greek resistance fighters (played by Irene Papas and Gia Scala) who join forces with the men – to draw female viewers to the cinemas.

Peck was sold on the film instantly. Brian Hannan details how casting Peck – a booming, square-jawed pillar of classic Hollywood – was a risk, with fewer box office hits in the Fifties than in the decade previous, 10 years since his last Oscar nomination, and industry criticism for making films abroad for the tax perks. His career at the time, said Hannan, was “patchy”. Biographer Gary Fishgall made a similar assessment, but maintained that to the public, Peck was still a major star.

Carl Foreman considered making the film in Cyprus, but the country was in a politically turbulent moment – on the brink of civil war. Foreman instead turned to the Greek island of Rhodes and met with the Greek prime minister, Konstantinos Karamanlis, for support. Greece supplied 1,000 troops as extras. But Rhodes was a demilitarised zone, so amendments had to be made to a treaty between Greece and Turkey, allowing the Greek troops to land there for the production.

Foreman even persuaded authorities to remove scaffolding from the acropolis at Lindos to capture some of the film’s grandest shots. The Greek military supplied more personnel and hardware: specialist mountain-climbing corps, destroyers, planes, helicopters, launches, armoured vehicles, tanks, howitzers, mortars and machine guns. An abandoned German fortress was also repurposed. “Virtually the entire manpower, and senior commanding officers, of the Greek army and navy were at the film’s disposal,” wrote Hannan. There were British advisors too, including Brigadier DST Turnbull, who had commanded raiding operations in the Aegean Sea.

Alexander Mackendrick was initially hired as director but left production before the film was put into action – either because of a bad back or because of clashes with Foreman, depending on which version you believe. “Foreman had a very specific way he wanted to do things,” says Rubin. “Obviously he had a clear eye on what he wanted and Mackendrick was not giving it to him.”

Quinn and Peck knew early on that Mackendrick wasn’t the man for the job. Quinn recalled that Mackendrick, while framing a shot, had asked for a boat – which was 15 miles offshore – to move three inches to the right. Peck had director approval and liked J. Lee Thompson based on his previous films, North West Frontier and Tiger Bay. Thompson was on-set for The Guns of Navarone just days before filming began.

Carl Foreman, however, had wanted to direct the film himself. “I feel like an artist who has to keep asking someone else to pick up his brushes and do the painting for him,” he said in 1961. “That must have led to certain tensions on the set, I can’t help but thinking, with such an interventionist producer,” said film historian Sir Christopher Frayling, in a making of feature.

There was also talk of tension and professional rivalries between the stars. Thompson recalled that Peck, Niven, and Quinn were “all eyeing each other warily and wondering which of them was going to come out ahead”. Assistant director Peter Yates described how Thompson appeased egos by doling out the close-up shots fairly.

There’s a stirring, old school pleasure in seeing the specialists assembled on-screen (now a well-worn trope seen in everything from Ocean's Eleven to Fantastic Mr Fox). Peck is Mallory, the expert mountain climber; Quinn as Stavros, a tough-as-nails Greek who blames Mallory for the death of his family; Niven is Miller, the genteel explosives man; Baker is Butcher, a knife fighter who’s lost his killer instinct; James Darren is Pappadimos, a Navarone native with a heck of a singing voice; and Anthony Quayle is Franklin, whose real speciality is that he’s lucky.

Still, Franklin’s luck runs out when they climb the cliffs of Navarone and he badly hurts his leg. Should they leave him for the Nazis to interrogate? Carry him around on their mission? Or chuck him back over the cliff?

It begins a tussle of macho egos, moralising about the war, and – ultimately – a deep bond between heroes. The sexual tension is indeed palpable. Foreman admitted that the film’s homoeroticism was ahead of its time, and Peck observed the dynamics: “David Niven really loves Tony Quayle and Gregory Peck loves Anthony Quinn. Tony Quayle breaks a leg and is sent off to hospital. Tony Quinn falls in love with Irene Papas, and David Niven and Peck catch each other on the rebound and live happily ever after.”

Whatever tensions might have existed behind the scenes were soon alleviated when Quinn brought out his chess board. Cast and crew became ardent chess players, with several games on the go at once.

J. Lee Thompson recalled that Quinn won most games though Peck was “very competitive and really began to improve his game during the shooting of the film.” Quinn met his match in Niven’s 14-year-old son, Jamie, who turned up on set and wiped the floor with everyone. “The kid beat Tony,” said Peck about their big showdown. “We were all so happy about that.”

Production was so popular that the King and Queen of Greece visited the set with other members of the royal family. Some royals wanted to be in the film, and scored roles as extras in one of the film’s best scenes – the crew being captured at a wedding party (the scene was an excuse for James Darren, a pop star, to do some singing). The film fell out of favour, however, when J. Lee Thompson went gung-ho with explosives and sank one of the on-loan ships. The navy withdrew cooperation and the captain was court martialed.

Back in Blighty, Shepperton Studios dedicated two soundstages to the film: one for the water tank and ship, and another to the actual guns of Navarone. The guns set was the biggest ever constructed for a British film – a three storey behemoth that cost more than £100,000. Heavy rainfall caused the roof of the set to cave in, which cost another £20,000 to rebuild. The guns, said Foreman, were the most expensive movie props of all time.

The finale of the film, for which the guns were built, is truly magnificent. Peck and Niven’s characters infiltrate the Germans’ gun fortress and set up the explosives, rigging the charge to an elevator that will detonate – and will take out the guns and a load of Nazis in the blast – when the elevator drops.

With the Germans close to catching them in the act, and the British destroyers on their way to rescue the stranded troops, it's a race against the clock. “The last 30 minutes of the movie – once they get to the gun cave – is probably the most pulse pounding, nerve-wracking nail biting ending for a war movie ever,” laughs Steven Rubin.

The question is: will the elevator drop low enough before the guns blast the British destroyers? Naturally, the heroes escape and watch from a distance as the plan works and the guns explode. The film never takes itself entirely seriously, but discovers – just as Foreman intended – humanity in the heroics.

Premiering in April 1961, The Guns of Navarone was – to coin the contemporary phrase – a mammoth success. Steven Rubin remembers seeing the film at a “roadshow” in California – a limited, big scale screening that made the film a must-see hot-ticket. It took $29 million worldwide – more than a quarter of a billion in 2021 terms – and scored seven Academy Award nominations. It won the award, unsurprisingly, for special effects. “We used to refer to the film as the biggest B-feature ever made,” said assistant director Peter Yates.

The impact of the film was felt in follow-up war epics. “Starting with Navarone, the idea of putting major Hollywood stars together in one epic adventure film because the thing to do – The Longest Day, The Great Escape, The Dirty Dozen,” says Steven Rubin. “Studios were thinking, ‘We’ve got to get audiences back in the movie theatre – we’ve got to pack these movies with as many stars as possible!'”

The Guns of Navarone was true “event cinema”. “It carries on today with Marvel films,” says Rubin. “Every studio has their tentpoles.”

Guns of Navarone is available on 4K Blu-ray now