Fukushima: From samurai training to skiing, this beleaguered Japanese prefecture has it all

Japan might be criss-crossed with bullet trains and jam-packed with vending machines selling everything from frozen drinks to hot cans of coffee, but in the historic town of Ouchijuku, in the heart of Fukushima prefecture, time stands still.

When I order a coke from a local shopkeeper, he dashes to the nearby gurgling stream and scoops up a bottle from the semi-submerged crate. Who needs fridges?

Eight years after the 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami, growing numbers of visitors to Japan are venturing off the beaten path, swapping the Blade Runner-like organised chaos of its cities for more rural areas.

The coastal prefecture of Fukushima was hit hard by the tsunami in more ways than one, partly due to the nuclear disaster at a power plant. But it’s also Japan’s third-largest prefecture – a rural paradise with a wonderfully rugged coastline, lake-dotted forests and extinct volcanoes.

Its close connections to neighbouring prefectures – Ibaraki and Tochigi – date back to the 17th century and the historic Oshu-kaido route, created to connect Tokyo (then known as Edo) with the north. Merchants who travelled through Fukushima needed places to rest, and many towns and villages sprang up.

Ouchijuku is one of the best-preserved examples. It’s been painstakingly restored to its former glory – shopkeepers sell wares from traditional thatched cottages, electricity wires have been buried and owners of the food stalls lining the unpaved main street specialise in traditional delicacies – the same fragrant chunks of roasted fish and steaming bowls of soba noodles which once sated hungry merchants’ appetites.

It’s easy to imagine that some of them might have bedded down at the six-bedroom Nakamuraya Ryokan in the Fukushima hot-spring town of Iizaka Onsen. It’s certainly a popular resting place for the region’s growing numbers of visitors. Run by the same family for 120 years, it was already a successful ryokan when current owner Hiroshi Abe’s ancestors took the reins. Inside, little has changed. I take a seat on woven tatami mats surrounding an open fire for the check-in process, before being led up a winding wooden staircase to my beautiful room, with its sliding screen doors and wooden shutters. I sleep Japanese-style, on a futon on the floor with my head resting on a (surprisingly comfortable) buckwheat-filled pillow. The next morning, Hiroshi tells me the business will be passed on to his eldest son, who’s currently backpacking around New Zealand. “English will become more important as Japan opens up to the west,” he says with a shrug.

The ryokan’s success is partly down to its position, metres from one of Japan’s oldest community onsens. In the morning, we join locals for a dip. A friend with a tiny tattoo is asked to cover it – in Japan, tattoos are frowned upon and associated with the Yakuza.

I find myself unleashing my inner hard man at my next stop-off, where I’m soon beating a Japanese pensioner with a wooden sword. The Fukushima town of Aizu-Wakamatsu (otherwise known as Samurai City) is in Aizu, a region once home to the feared Aizu samurai clan. I jump at the opportunity to sign up for a lesson in the martial arts discipline of kendo. It takes place in a low-slung building in the shadow of the beautiful Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle, a replica of a 14th-century hilltop castle destroyed shortly after the Boshin War in 1868.

After a quick lesson, I’m invited to practice my skills on one of the tutors. I step forward to face my masked assassin, who stiffens his shoulders before revealing some of his limited English by bellowing “Come on!” in a way that reminds me of a drunken fight I once witnessed in a Basingstoke bar. I tentatively tap him on the head, but it’s not enough and he reveals the third English word he’s perfected (probably after years of shouting at frightened British trainees). “Harder!” Sod it, I think, and whack him again. It does the job, although I feel an inevitable pang of guilt when he removes his mask and I find myself staring at the smiling face of an elderly Japanese man.

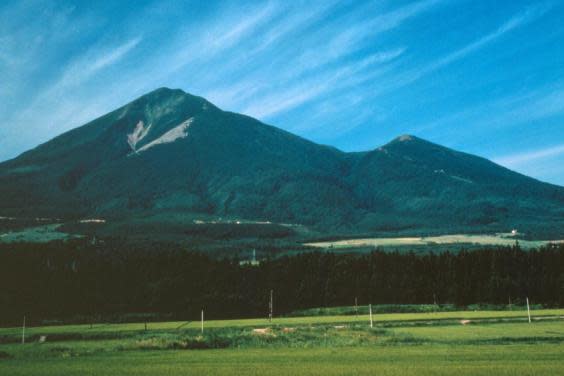

I decompress with a visit to Grandeco ski resort, inside Bandai-Asahi National Park. A cable car whisks me skywards and I set off on a breezy autumnal walk through golden beech trees, keeping an eye out for the park’s black bears. The eruption of Mount Bandai in 1888 reshaped this entire area. On the putting green opposite the Hoshino Resorts Bandaisan Onsen Hotel, golfers navigate huge boulders which belched out of the volcano. The eruption formed enormous bodies of water, like Lake Hibara. Villages were covered, and when water levels drop it’s possible to see the tips of submerged torii gates. It’s a reminder that devastating floods have always been part of life here, and I’m further reminded of Fukushima’s resilience by the region’s mascot. A bright red cow, made from two pieces of wood, it’s a colourful beast of burden who’ll steadfastly shoulder the weight of the region’s troubles. Personally, I think he’s doing a pretty good job.

Travel essentials

Getting there

British Airways flies from London Heathrow to Tokyo from £733 return.

Staying there

Doubles at the Nakamuraya Ryokan start from £70.

More information

Download the Diamond Route app to get the low-down on Fukushima and its neighbouring prefectures of Ibaraki and Tochigi.