The First 11 Minutes of 'Raising Arizona' Are the Best Opening To Any Movie Ever Made

The opening minutes of a movie can be a make-it-or-break-it proposition. They’re like the first 50 pages of a novel. If the author hasn’t hooked you and reeled you in by then, well it’s time to move on to the next book on your nightstand. Of course, no one’s going to get up and walk out of a movie after ten minutes—not when they’ve already forked over fifteen bucks. But a less than great start puts a director at a disadvantage. He or she has to win you back.

I keep a list of movies with perfect openings filed away in my head, from tried-and-true classics like Casablanca, Sunset Blvd., and Touch of Evil to more contemporary kick-starters like The Road Warrior, the Dawn of the Dead remake, and Magnolia. These are movies, each and every one of them, that reach out and grab you by the jugular either by the sheer break-neck force of their pacing, virtuosic camerawork, or the economy of their narrative table setting. They create a world—no, an entire cinematic universe—in a very short amount of time. Watching them, you get the giddy sense that you’re on a great ride before that ride has barely even started.

Still, I’d argue that the greatest opening of any movie ever made are the first eleven minutes that come before the title card of Joel and Ethan Coen’s Raising Arizona. Is it my favorite movie of all time? No. Hell, it’s not even my favourite Coen brothers film. But as far as cinematic first impressions go, nothing can possibly hold a candle to it. I remember seeing the movie shortly after came out in the spring of 1987. I was at the tail-end of my senior year of high school and just beginning to fall in love with movies in a way that went beyond just pop entertainment. I was starting to take note of directors, writers, and cinematographers, not just the stars. And as soon as Raising Arizona began, I just sat back in my seat in awe the way I imagine someone who has a born-again conversion looks at the world anew. Eleven minutes later, I had been baptised into a new religion that would still be my faith nearly 35 years later.

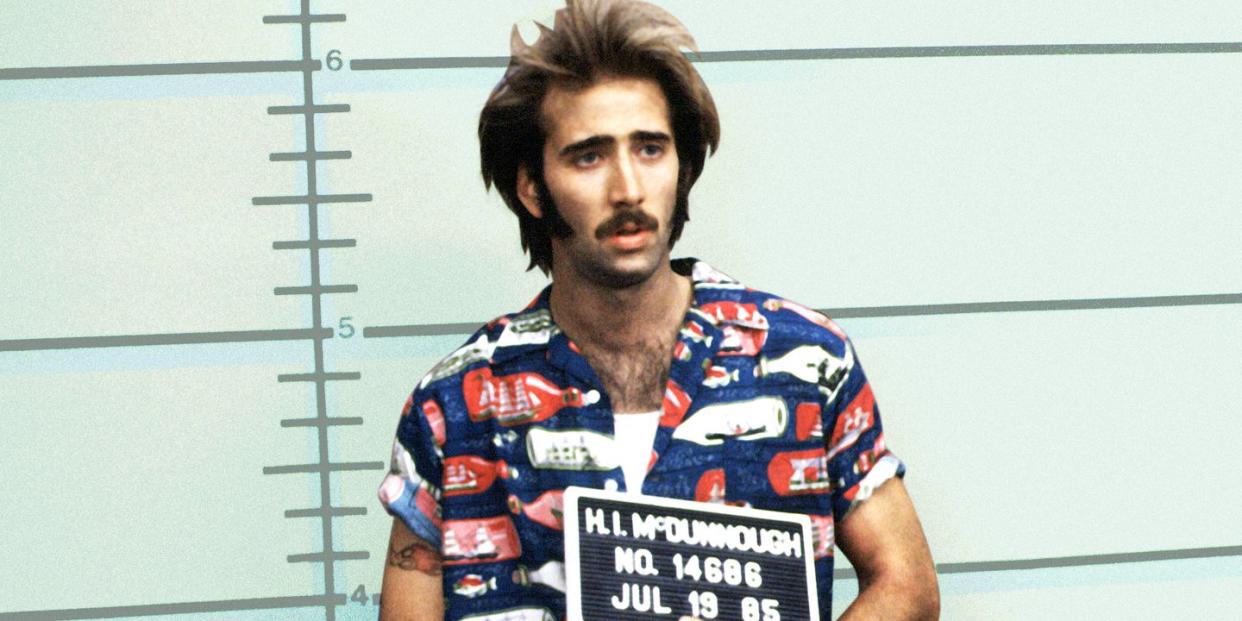

Raising Arizona was only the Coen brothers’ second feature film (the first was their 1984 neo-noir Blood Simple). And while Joel and Ethan were just 29 and 32 respectively when it hit theatres, here were two guys who were clearly already masters, both in terms of technique and storytelling. In the off chance you haven’t seen it (and really, what are you waiting for?), Nicolas Cage plays an unlucky convenience-store robber named H.I. McDunnough who keeps getting imprisoned and paroled. On each turn through the revolving door of the Arizona penal system, he gets his mug shot taken by and flirts with Holly Hunter’s police officer Edwina. On his final arrest, he slides an engagement ring on her fingers while she’s taking his prints and while inside his cell, he dreams of “a future that was only eight to fourteen months away.”

Once he’s out, he goes straight, they get married, and plan on starting a family. Then, Edwina finds out that she’s unable to have kids. “At first, I didn’t believe it. That this woman that looked as fertile as the Tennessee Valley could not bear children,” says Cage’s H.I. via voiceover. “But the doctor explained that her insides were a rocky place where my seed could find no purchase.” So the distraught couple hatches a plan to kidnap one of the five babies just born to Nathan Arizona (“and hell, you know who he is…”), the biggest unpainted furniture magnate of the American Southwest.

If it sounds like I’m giving a lot away, I’m not. Because all of this—and so much more—is unspooled before the opening credits appear on screen. Eleven perfect minutes of spoken and visual exposition goosed along by Barry Sonnenfeld’s daredevil cinematography and Carter Burwell’s caffeinated banjo music peppered with Hank Williams-style whistling and yodelling. With this bravura intro, the Coens were throwing down the gauntlet as if to announce their arrival as master filmmakers. And not the ageing New Hollywood movie-brat variety who took themselves oh-so seriously. They were more interested in evoking the playful, merry prankster spirit of Tex Avery and Looney Tunes shorts. Watching those eleven minutes back in 1987 felt like witnessing the future. And it wasn’t a future that was eight to fourteen months away. It was now.

You could write a doctoral dissertation on the pre-title sequence of Raising Arizona (and I’m sure someone has). But what makes it so singular and indelible to me is how, in a medium that’s so often devoid of any personality signature or idiosyncratic stamp, these eleven minutes could only be made by two people—two people sharing the same set of influences, sharing the same artistic voice, and it just so happens, sharing the same DNA. The genius of the kick-off sequence is all in the details—the little touches and call-backs and grace notes that adrenalize the action. I’m talking about the unseen guy off-camera who keeps telling Hunter mid-mug shot, “Don’t forget the profile, Ed!” or “Don’t forget his phone call or “Don’t forget his fingers, Ed!” On her wedding day, as she’s staring at herself in the mirror in her white dress, his voice returns one last time: “Don’t forget the bouquet, Ed!”

Then, there’s the old cellmate in the bunk above H.I. in prison who starts telling a story about his family being so poor that when there was no meat they had to eat frog, and when there was no frog they ate crawdad, and when there was no crawdad they ate sand. “You ate what?” We ate sand. “You ate sand?!” When H.I. returns to prison just a couple of montage minutes later, the same prisoner is still on the top bunk talking about how to prepare crawdad. There’s also M. Emmet Walsh as H.I.'s sheet metal-drilling coworker telling a fractured anecdote about a friend finding a head in the highway after a car crash. There’s the repeated flashes of the same gorilla-looking inmate mopping and snarling at H.I. every time he returns to the joint. There’s the group-therapy sessions in jail where we get our first glimpse of John Goodman, the parole-board hearings telling H.I. to straighten up and fly right, and the magnetic larcenous pull of the convenience stores H.I. drives by even though they’re not on the way home. There are entire worlds in details like these.

But the most incredible thing about the opening of Raising Arizona is how it lays out an entire love story between two people quicker and more effectively than most movies do in two hours. We see boy meet girl, boy flirt with girl, boy console girl, boy propose to girl, boy marry girl, boy stare down disappointment with girl, boy console girl again, and finally, boy plan a felony with girl that will walk us up to the subsequent 83 minutes of the film. It’s like witnessing the entire arc of a romance—a life, really—with your finger on the fast-forward button.

What amazes me most, though, is the Coen brothers’ flat-out ballsiness deciding to have the opening of Raising Arizona unfurl as long as it does. Of course, having an extended prologue like this isn’t totally unheard of. But it certainly isn’t common. The pre-titles sequence of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is longer (20 minutes). As is The Departed (18 minutes), Mission: Impossible—Fallout (16 minutes), and Avengers: Endgame (15 minutes). Heck, it isn’t even the longest on Cage’s filmography. His awesome midnight-movie freakout, Mandy, doesn’t announce the title on screen until 75 minutes in (!). All I’m saying is, it’s hands down the most seductive and flawlessly constructed cinematic come-on ever.

The reviews, however, weren’t as breathless as the high-school me was. In fact, I remember sitting in our living room in 1987 watching At the Movies on television. Gene Siskel gave it a thumbs up (with reservations); Ebert gave it a thumbs down. As the two critics began to wind up their discussion of the film, Siskel favourably compared Raising Arizona’s quirky New West milieu to David Byrne’s True Stories. Ebert, who was buying the analogy but not the verdict, then challenged his cohost across the aisle to return to this question in five years to see which of the two films people would still be talking about. Now, 34 years later, when was the last time you heard anyone sing the praises of or even mention True Stories (or even any eleven minutes of it)? I thought so. The prosecution rests.

You Might Also Like