Fiona Phillips: 'I watched my mother slip away into loneliness as I was too busy with my own family'

"WHENEVER you speak to an elderly person on The Silver Line, they always say the same thing,” reflects Fiona Phillips.

“They tell you what busy lives their adult children lead and then they go to explain what important jobs they do and why they haven’t got the time to visit or even stay in touch. There’s real pride, despite their aching loneliness. It’s heartbreaking to hear.”

Television presenter Phillips, 58, who is an ambassador for The Silver Line, has first-hand experience of staffing the phones at the charity.

But she has also seen things from the opposite perspective, having been that adult child with that busy life as first her mother, then her father succumbed to the bewildering anguish of early onset Alzheimer’s in their 50s.

“I tried to be there for my parents as much as I could, I really did; but I was working on GMTV, I had two small children and Mum and Dad lived 400 miles away in Wales.

“I would spend hours hurtling up and down the motorway with the kids bawling in the back but all I was able to do was firefight as their health deteriorated. My mum and I spoke on the phone a lot – but I still feel it wasn’t enough.”

It’s an all too familiar story and a reflection of our modern world, where families inevitably splinter as opportunities take offspring in different directions.

“There’s a snapshot in my mind of my mum, sitting alone on a park bench, fragile, crying and lonely,” says Phillips. “I used to take her along to the hairdresser’s every month but on this occasion she’d wandered out on her own and had no idea what was going on.”

Back in the mid-Nineties, Phillips – who has two sons aged 17 and 20 with her television producer husband Martin Frizzel – ruled the breakfast sofa, alongside Eamonn Holmes.

“Things were happening in my parents’ life that I didn’t know about,” she says quietly. “My lovely mum was suffering, in grip of something awful, but she never made a fuss.”

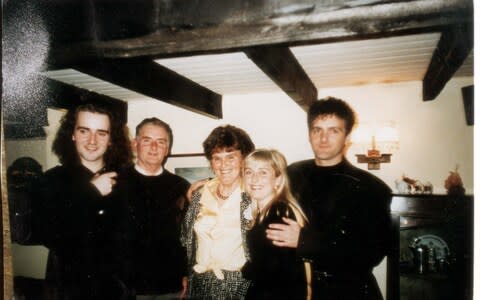

Phillips, a grafter who took on a paper round aged 11 and was living on her own in a bedsit aged 17, credits much of her success and fierce independence to her mother, Amy, who gave up work to raise her daughter and two sons.

“My mum was always beaming with pleasure, kind and affectionate, and made us feel so loved,” she remembers.

“She was an unworldly sort of person who believed the best in everyone and always found a way to smile through the tears and look on the bright side; that’s why it was so tragic to see her slowly disappearing before my eyes.”

Her father, Phil, had served in the Navy but then retrained as a television repair man. He was taciturn and reserved; this emotional mismatch drove a wedge between them as dementia took hold.

“My dad used to complain that mum kept falling over and I started to notice her smile would falter. She grew anxious and irritable and was just not herself,” says Phillips. “But she was prone to depression so we attributed her behaviour to that.”

As Phillips’s career flourished, she visited her parents in Wales and spoke to her mother on the phone. But she had little concept of how her mother’s health was deteriorating.

“Then I had my first baby and I knew she would be utterly overjoyed so I called her up and said ‘It’s a boy!’.

Her mother’s response was devastating. There was no sense of delight or hint of congratulations.

“She just said ‘Never mind’,” says Phillips. “I was furious that she had ruined one of the happiest days of my life by treating my son like he was some sort of mistake.”

It was only when her mother visited to see the baby that Phillips realised something was very wrong.

Frizzel went to collect his mother-in-law at the coach station where she was upset she’d lost her bag. There was one suitcase left on the coach; it contained all of her things, but she failed to recognise it as hers.

“Mum didn’t seem able to cope, never mind help,” recalls Phillips. “I found her in the kitchen crying that she didn’t know how to make a cup of tea. Another day she kept emptying her purse and counting her coins out loud, over and over. More than once she appeared in our room and clambered into bed with us.”

Amy had been diagnosed with depression and prescribed strong medication. She was actually in the grip of early onset Alzheimer’s, but because she was in her 50s, she remained undiagnosed.

“It seems so obvious now,” says Phillips.

“But back then we were just confused. What made it worse was that, when she was finally diagnosed, the GP didn’t tell us on the grounds of patient confidentiality – which is insane in cases of dementia when the family needs to know what is going on.”

Phillips only found out by chance when she visited and, on asking where her mum was, her dad said she was “at the day centre”. As her mum’s condition worsened there would be phone calls to the GMTV studios from the police – one was to say that her mother had left a chip pan on which had caught fire and burned her

Meanwhile Phillips’s father was deeply unsupportive and unsympathetic towards his wife, dismissively referring to her as “that bloody woman”. His cold detachment was nothing short of shocking.

“I really resented my dad for not caring more and I got increasingly annoyed by his horrible selfish attitude.”

Amy was eventually moved into a care home and died in 2006, without making a will.

Phillips brought her father to the solicitor’s office to begin the process of sorting her affairs. But the solicitor contacted her to say that her father wasn’t able to function; he couldn’t remember the names of his sons or his own date of birth.

With bitter irony, he too was then diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s. Phillips, again wracked with self reproach, eventually moved him to sheltered accommodation near her London home when it became clear he was no longer able to look after himself.

“The police would call me because he’d been found wandering about in the middle of the night,” sighs Phillips with a helpless shrug. “But at least he seemed happier than Mum did.”

Eventually something had to give. In 2008, halfway through her contract, Phillips walked away from one of the most coveted jobs in broadcasting to manage the demands of family life.

It was a wrench but also a relief; less a sacrifice more a pressing necessity as her mental health was being severely affected by the turmoil.

After leaving GMTV, Phillips continued to work; on *Panorama*, *Dispatches* and a spread of consumer programmes.

Much of the subject matter was age-related, including the documentary *Mum, Dad, Alzheimer’s and Me*, which her father took part in and enjoyed with unaccustomed gusto.

He died in 2012. But seven years on, Phillips is still tormented by endless “what ifs”.

“I know that Alzheimer’s is a disease that erodes mental and then physical health to the point where there’s very little you can do to alleviate the crippling pain of feeling cut off,” she says, quietly.

“But I find myself ruminating over the solitude that so many elderly people face and how crushing that must be.”

At one point Phillips took part in an experiment on loneliness in which she spent a week living in complete solitude. She was initially relishing a break away from her responsibilities – but, to her surprise, within two days she was miserable.

“People need other people to survive,” she says. “After not speaking to anyone for 36 hours I was literally walking the streets trying to catch someone’s eye.”

In coffee shops she was desperate to chat but the other customers were invariably wearing headphones and tapping away on a laptop.

That brief experience of feeling overlooked and pushed to the margins further fuelled her determination to support the elderly.

“Through The Silver Line, an older person can receive regular calls,” she says. “You cannot underestimate how much someone benefits from knowing another human being has thought of them and reached out to them.

“Older people need that connection – they deserve that connection. Please help us to help them.”

The Silver Line, which arranges weekly phone calls to lonely elderly people by friendly volunteers, is one of three charities supported by this year’s Telegraph Christmas Charity Appeal.

Our two other charities are Leukaemia Care, which provides support to individuals and families affected by blood cancer; and Wooden Spoon, which works with Britain’s rugby community to raise money for sick, disabled and disadvantaged children.

To make a donation, visit telegraph.co.uk/charity or call 0151 284 1927