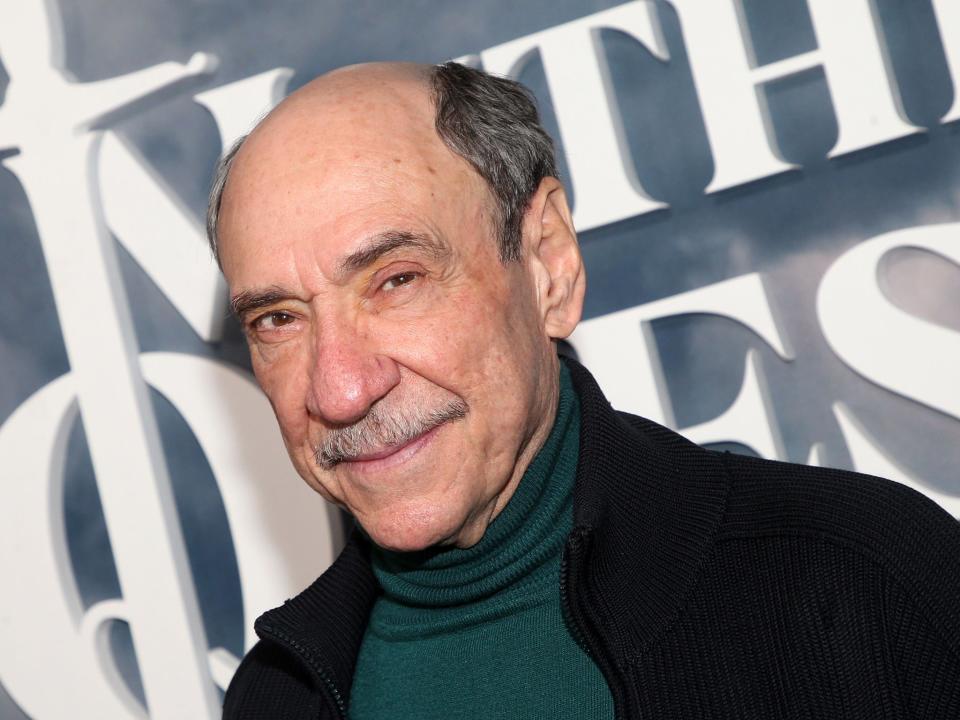

F Murray Abraham: ‘I used to be a pain in the ass, but I’m absolutely wonderful now’

F Murray Abraham is bellowing down his camera lens about an actor he found unbearable. “He was a nightmare!” he roars. The star of stage and screen is in full blaze, not unlike his Oscar-winning turn as the malevolent Salieri in Amadeus. Only he’s a few decades older now, and on Zoom. “I said: ‘never again’. Years passed, and I bumped into him on the street and he seemed very nice. So I took this other film with him, and it was a disaster. He was the same bum he was originally!”

Disappointingly, Abraham won’t name the actor in question. Is this person still with us, at least? “Unfortunately, yes.” A mental note is made to scour his IMDb page for clues later on. “But some people like to work that way,” the 81-year-old continues. “They like to start conflict, you know?” He takes a breath, as if weighing up whether or not to go further. “I used to be kind of a pain in the ass, but I’m absolutely wonderful now.”

For better or worse, Abraham’s reputation precedes him. Today, the actor is an unexpected funnyman. On Apple TV+’s Mythic Quest, which begins its second season this week, he brings theatrical verve to the role of a clueless sci-fi novelist who writes the back-stories for video games. He’s best known, however, for his villains: the aforementioned Salieri; a ruthless music manager in Inside Llewyn Davis; Frank Lopez’s underboss in Scarface. If he’s in something, he’s probably being dastardly in it. Off-screen, he seemed to follow suit. In the wake of Amadeus, Abraham’s name would become shorthand for Oscar winners who struggled to follow up their awards victories with work of equal acclaim. Before and after his win, rumours of feuds and on-set discord stuck to him.

He apparently clashed with Sean Connery on the set of 1986’s The Name of the Rose, leading director Jean-Jacques Annaud to dub him an “egomaniac”. Meg Tilly, who left the cast of Amadeus a few weeks into production due to an injury, has called him “a terrible person”. Why was he so difficult to work with back then? “Well,” he sighs. “It was just hubris. That’s all. I started to really believe some of the reviews I was getting. I really thought I knew what I was doing. I didn’t know any more then than I do now, but I felt like I should be treated with a little more respect and all that crap.”

Has he tried to make amends with those he may have hurt? “That’s interesting,” he says, patting his chin. “Some of my closest friends are alcoholics. They’ve cleaned up. Three of them, actually. But they talk about the 12-step programme, and how one of the steps is making amends. And what I did, when I took to heart what they were saying, was I tried contacting all the people I thought I had offended. Because there were things that I remembered having done that I was so embarrassed about. Things that I’m not proud of at all. So I contacted a bunch of people, and some of them accepted my apology. Some didn’t know what the hell I was talking about. Some never responded at all. I did try. But it was a great relief.”

Abraham is chatting from the Manhattan apartment he shares with his wife of 58 years. He is witty, candid and undeniably a little scary. At one point during our conversation he suddenly erupts, calling out for a live-in healthcare professional to shut the door to the room he’s sat in. As a request, it’s innocuous, yet delivered with the ferocity of Zeus. It’s that famous voice of his that does it, with its silky gravity and immaculate enunciation. Abraham could probably make ordering a pizza sound vaguely menacing.

On Mythic Quest, a workplace comedy set in a video game studio, he’s nowhere near as frightening. He plays CW Longbottom, a once-revered author of “unbridled space smut”. He’s also the not-entirely-clued-in octogenarian responsible for all the parts of a hit game that its players don’t particularly care about – aka the “cutscenes”, which develop character and provide exposition yet interrupt gameplay. The show has similar rhythms to the cult sitcom Community, with its proclivity for the eccentric and the unexpectedly powerful. A season two episode of Mythic Quest – that’s more or less a two-hander between him and guest star William Hurt – probably marks the first time Abraham has been asked to deliver both an emotive monologue on grief and authorship and defecate in the top drawer of a writing desk. But he’s admittedly been around for a while, so who’s to say?

“Don’t get me started on how much I like this show,” he beams, before heaping praise on his fellow cast members, including It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia’s Rob McElhenney, the show’s crew and even its “first-rate” catering. “After Amadeus, I became known as a ‘heavy’, but I’ve always preferred to make people laugh.” Is it strange to have appeared in so many comedies on stage – including A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Sexual Perversity in Chicago and many by his late friend Terrence McNally – yet be known as deathly serious? “It is an odd disconnect. It’s a little frustrating. But in most of the villains that I’ve played, there’s always a hint of humour. Fortunately for me, the people who run Mythic Quest recognise that in me and I’m forever grateful.”

The show also marks a return to his roots. Despite a dramatic adolescence growing up on the border of Mexico – he’s regularly referred to his teenage self as a “hoodlum” – Abraham gravitated towards comedy when he caught the acting bug via one of his teachers. He is hilarious as the flamboyant proprietor of a gay bathhouse in 1979’s The Ritz, a big-screen adaptation of McNally’s celebrated play, but struggled professionally in its wake. “The only parts I was offered for about a year after that were gay roles,” he remembers. “I didn’t mind, I’ll do anything, but I said... you know, I can do other things.”

He also grew angry. He remembers working as an extra, in his early film days, and being outraged at how the stars sometimes treated the crew. He was so outraged, in fact, that he began writing down their names on a little piece of paper. “I said, ‘One of these days I’m going to be famous, and when I am, I’m going to get even with you and you and you,” he says, stubbing his finger towards the camera lens for emphasis. One day, he continues, he was caught in an enormous downpour. Undressing at home, he took the paper with the list of names on it out of his pocket, and was horrified. “The ink had run. And I kept looking at the list trying to figure out who was on it. I remember thinking, ‘Next time, I’m going to write this list in pencil!’. And as I was saying that I thought: you know, you’re crazy!” He chuckles to himself. “It was the luckiest thing. Throw that list away, baby! God’s trying to tell you something.”

That didn’t rescue him from later hubris, though. Abraham is nicely aware of his contradictions, and that his strict moral code about the behaviour of others didn’t stop him from messing up himself. “The worst thing is you don’t think you’re doing it,” he says. “You keep telling yourself, ‘Well, I’m certainly not succumbing to that!’ But when you say that, it means you are.”

Amadeus had come as a shock. While he was known on the New York stage at that point, Abraham’s casting in the film was unexpected – director Milos Forman had deliberately sought out relative unknowns for the parts of Salieri and his rival Mozart. It opened up a floodgate of attention and opportunity, but also shrunk his social circle. He lost many actor friends. “After my success, they began to drift away. Not all of them, but… it’s almost as though they were a little upset that they hadn’t experienced the success that I was experiencing,” he says. “It’s a delicate line to tread. It really is. Because I think I was probably insufferable. I’m not insufferable now, I really am not.” He lets out a half-laugh. “I have to keep telling myself that! But I think that I was insistent on being right about everything. I mean, that’s absurd, you know? I’m sure I went through a period like that. That could be why I lost some of those friends, by the way. I mean, I’ll take the responsibility.”

Post-Oscar, Abraham at first rejected villainous parts that riffed on Salieri and took up on an offer to teach incoming drama students at Brooklyn College instead. The quality of his film roles subsequently began to dim. He was in a low-budget sci-fi film called Slipstream with Mark Hamill, and played Arnold Schwarzenegger’s duplicitous best friend in Last Action Hero. Before his recent on-screen resurgence, in series like Homeland and films such as Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, Abraham’s fluctuating fortune was made easier by his wife, he says. They’ve been together since 1962, and have two children. “She’s been a rock to me. She put up with my tirades and my anger and my…” He shakes his head from side to side. “All that crap we put ourselves through.”

When Abraham speaks of his earliest years as a struggling actor, practically begging for work at New York’s Public Theater in the late Seventies, and then coming home to a comforting partner, it’s easy to think of Inside Llewyn Davis. The Coen brothers’ cast Abraham as a cold power-player left unimpressed by one of his auditionees. “I don’t see a lot of money here,” Abraham’s character surmises, in one of the most gutting cameos in recent memory. Did Abraham know a lot of men like that? “I still know them,” he jokes. “They’re running the country!” He based the character on “several” different people he’d encountered along the way. “Generally it’s really hard for me to hide the way I feel,” he says. “Every time I try, it’s like I’m being a phoney.” He’s sometimes managed it, but only when he’s been particularly hungry for work. “There are times when you need the job so desperately that you don’t tell the truth. You try to guess what it is they want. If you haven’t worked for six months, you’ll do whatever it takes, and that really hurts. It hurts your pride. But I’ve done it. I’ve been there.”

That’s the allure of performance, though, and what keeps him coming back to film sets and the stage. Abraham is 81, financially comfortable, and had more off-camera tumult than most. He’s entitled to a sit-down by now. But where’s the fun in that? He remembers his wife sitting in on an interview he was doing a few years ago. “They’d have 10 questions that they’d ask a working actor, and the last question was: ‘What would you do if you knew tomorrow was the end of the world?’ And my wife instantly jumped in to answer for me: ‘He’d look for work’.”

Mythic Quest season two is streaming now on Apple TV+, with new episodes premiering weekly

Read More

St Vincent: ‘At a certain point, we are all culpable. Just don’t be a s***ty person’