The Evolution of James Bond's Body, From Sean Connery to Daniel Craig

Finding himself opposite a fully naval-uniformed Commander James Bond was particularly surreal for Simon Waterson, who’d only just left his post as a physical training instructor in 845 Naval Air Commando Squadron. Should he stand to attention?

These days, the idea that a rookie PT might receive an out-of-the-blue phone call to go to Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, 20 miles west of London, and audition for a supporting role with the world’s least secret agent is as far-fetched as an invisible Aston Martin.

But this was a different time: 1997. And this was a different Bond: not Daniel Craig, arguably the most A-list of the V-shaped clients whose bodies Waterson would go on to transform: Chris Evans for 2011’s Captain America, Chris Pratt for 2014’s Guardians Of The Galaxy, all the Chrises, plus a Tom (Hiddleston), Jake (Gyllenhaal) and Benedict (Cumberbatch).

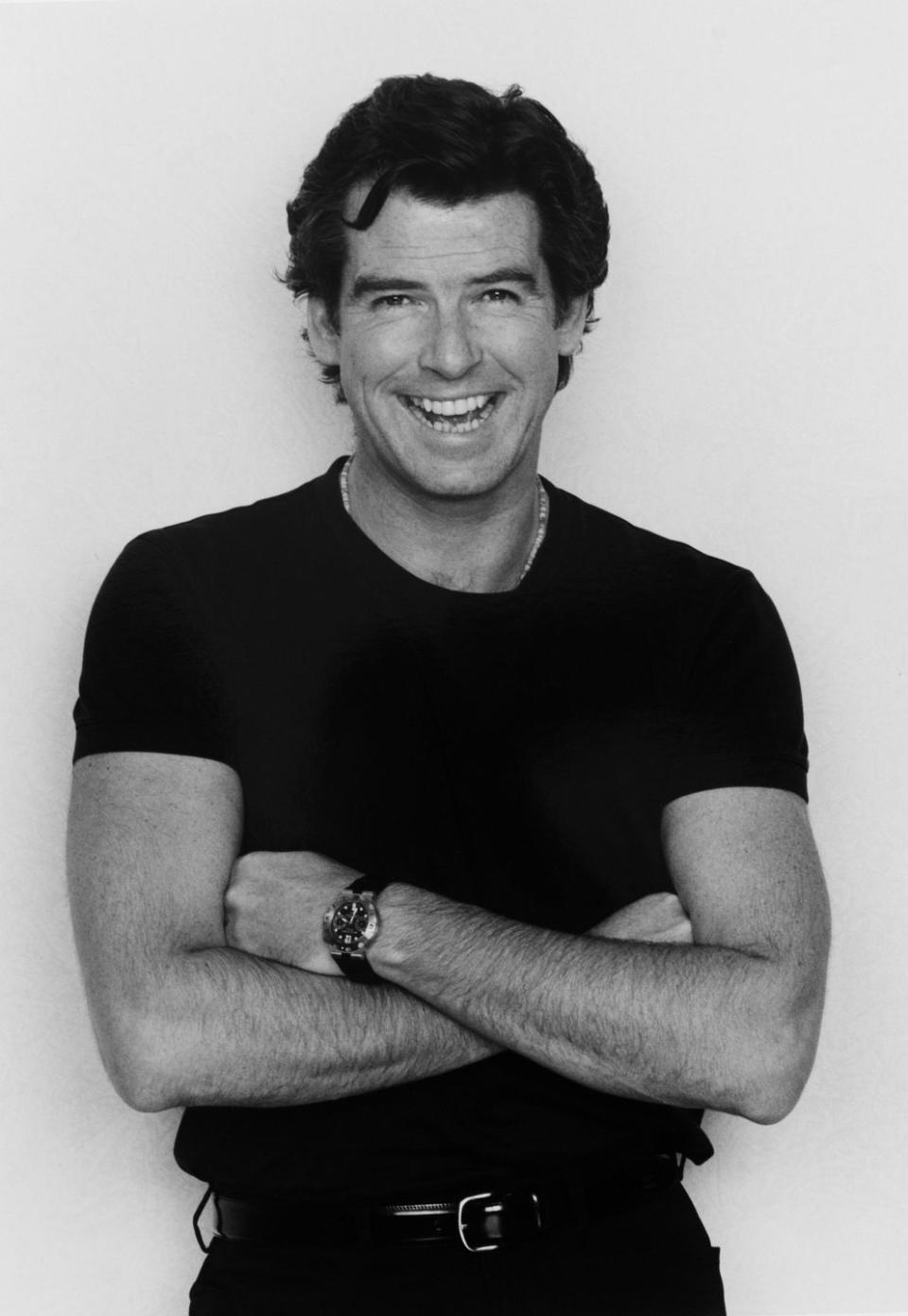

This Bond was the rather more lithe Pierce Brosnan, then filming Tomorrow Never Dies, his second outing in the tux (by Brioni). And there was “no really big aesthetic brief” for new recruit Waterson, now a veteran of seven Bond films and over 20 years on the franchise: “We weren’t in an era of Marvel superhero physiques.”

Brosnan’s third Bond film, 1999’s The World is Not Enough, presented some particular demands: lunges and other ski-type movements for the mountain sequences; agility, hand-eye speed, coordination and ducking under pipes for the fight with Robert Carlyle’s terrorist Renard aboard a sinking submarine. But mostly the order of the day was “generic fitness”, says Waterson. Be a training partner for Brosnan to lift weights and cycle with. Warm him up before strenuous scenes and cool him down after. Feed, water and supplement him. Maintain his energy. Stop him getting ill or injured.

Dislocating his collar bone after falling from a hot air balloon, Bond does get injured in the pre-credits sequence of The World is Not Enough - a franchise first for the hitherto remarkably unscathed character, but not the leading man. On Tomorrow Never Dies, Brosnan’s face required eight stitches after being cut by a stuntman’s helmet; the crew shot his good side. On 2002’s Die Another Day, while sprinting between explosions during the filming of the pre-credits hovercraft chase, his knee blew up. Filming was delayed - another franchise first - for seven days, while he flew to the US for surgery. Producers Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli likened the incident to “a super-athlete getting hurt”, while Brosnan’s recovery was “almost bionic”.

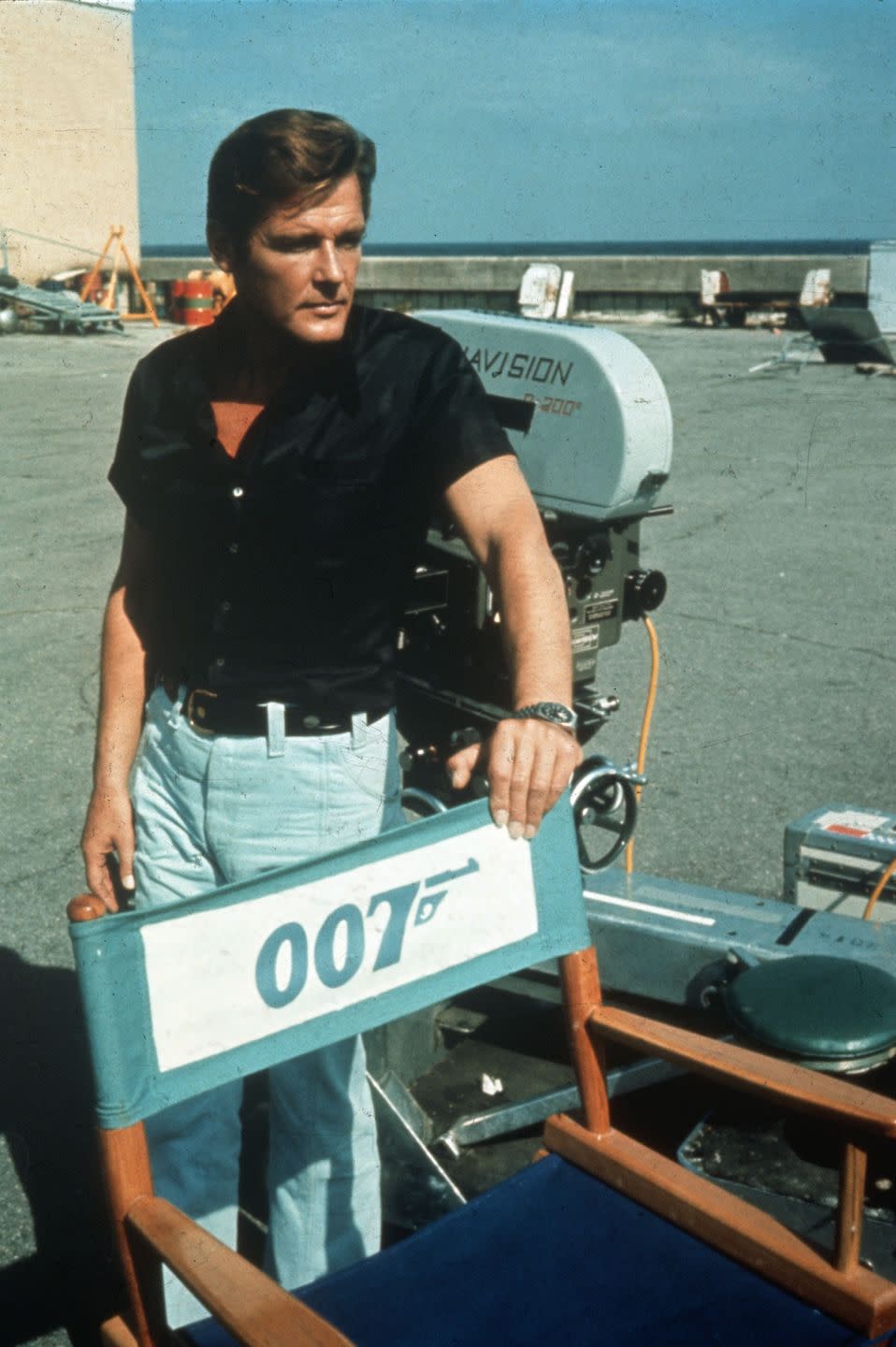

Making Bond films was “great fun”, Brosnan later said, but also “bloody hard work”, lamenting that an action scene could take weeks to film without him uttering a line of dialogue. By contrast, Roger Moore’s tenure had, a longstanding Bond crew member told Brosnan, been “a good old laugh”.

Die Another Day was deluged with CGI in an attempt to keep up with other blockbusters, and that paid off at the box office. But the highest-grossing Bond film to date was widely ridiculed for such cartoonishness as the Aston Martin “Vanish” and the undignified spectacle of a badly superimposed Brosnan surfing an ice tsunami. (For the pre-credits beach landing, he was body-doubled by surfer Laird Hamilton.) Nevertheless, Brosnan, a commercially successful and much-liked Bond, understandably expected to return for 2006’s Casino Royale, which would’ve been bang on the mid-Naughties trend for middle-aged action heroes: Rocky, Rambo, Indiana Jones, John McClane. Until, that is, a creative handbrake turn jettisoned the near-50-year-old like an unsuspecting DB5 passenger.

“Look, this game’s changing fast,” Lee Tamahori, Die Another Day’s director, told the Bond producers after a screening of The Bourne Identity with its raw stunts. “You’re going to have to rethink this.” An undercover source at Bond production company Eon cited “the opportunity to re-energise the franchise and take it to even greater heights.”

At 36, Craig was considerably younger than Brosnan had been when, at 42, he was cast in 1995’s GoldenEye. And Craig, says Waterson, came with “a very clear brief” aesthetically. “I said, ‘Look, I've got to look like I can kill somebody,’” Craig told an interviewer. “If I take my shirt off, it’s not: ‘Oh, nice body.’ It's got to be: ‘Oh, fucking hell, he could do somebody.’ I wanted to look like I could do everything Bond does.”

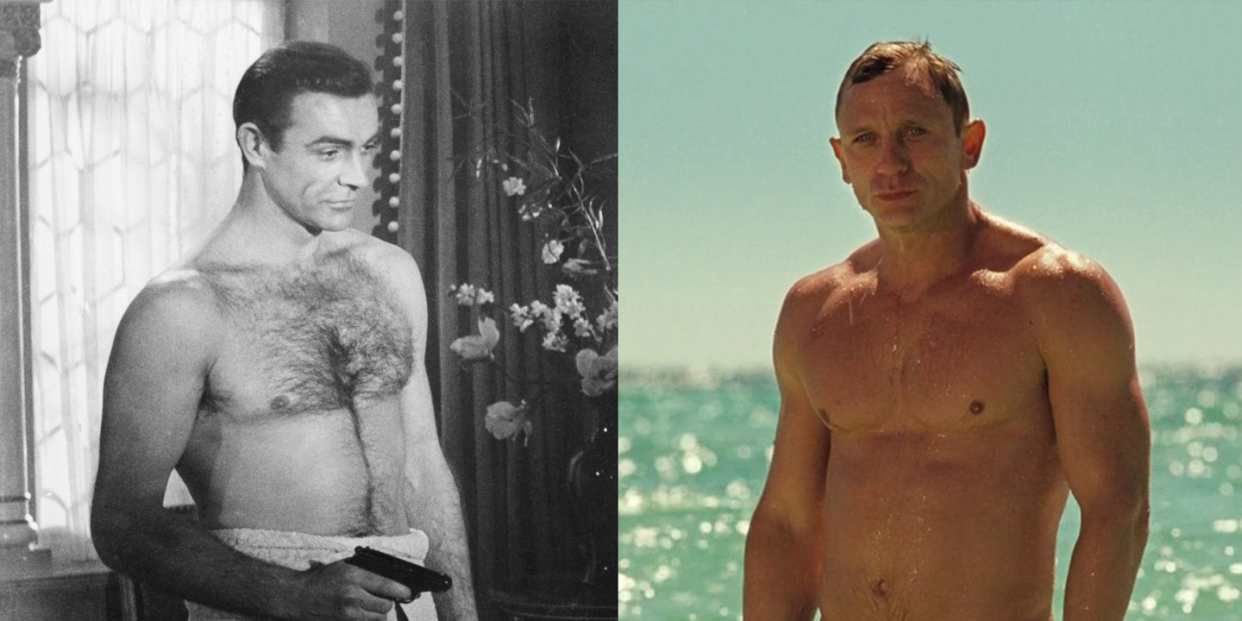

That shot in Casino Royale of Craig’s Bond emerging from the sea in his light-blue La Perlas was a defining moment of muscular definition in the near-60-year-old franchise. Protein-shaken and stirring, his pumped pecs unobscured by any Austin Powers shagpile, Craig unveiled a radically new body image for his rougher, tougher, buffer 007.

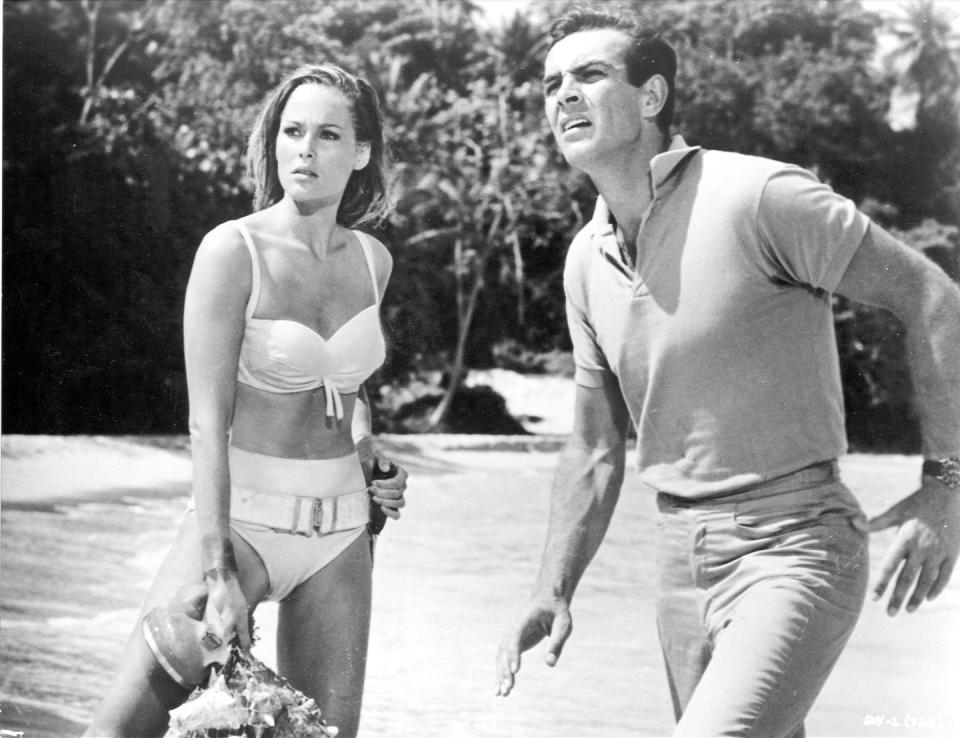

“In the way that Dr No was remembered for Ursula Andress coming out of the sea in her bikini, I suspect that Casino Royale will go down as the film where Daniel Craig walked on to a beach in tight swimming trunks,” actor and Young Bond novelist Charlie Higson said presciently. He speculated the “fantastic image” could change the history of British cinema by ushering in a new golden age of homegrown tough-guy action heroes in the mould of Richard Burton and Stanley Baker, and sweeping away “wimps like Jude Law and Orlando Bloom”. Even Moore “never looked like much of a threat to man nor woman”.

Craig’s rig made waves in other ways. He “was a much more physical Bond and his tailoring and wardrobe reflected this”, costume designer Lindy Hemming, who’d joined the franchise with GoldenEye, told the authors of the book Some Kind of Hero: The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films. And having watched Craig in action on set, composer Dave Arnold, who’d joined the franchise on Tomorrow Never Dies, felt Casino Royale’s title song “needed to be something much more muscular” than the usual “glorious velvet curtain”. Soundgarden frontman Chris Cornell, who co-wrote and performed “You Know My Name”, had a voice that, like Craig, “could kick a wall down”.

Craig didn’t just want to look like he could do everything Bond does: he wanted, as far as possible, to do it. “Of course, I didn’t do all the stunts,” he said. “The insurance company won’t let me. But at a certain stage in every stunt, you see it is me.”

The stunts Craig performed were “on a completely different level” from previous Bonds, says Waterson. He conditioned the necessary athleticism and “functioning muscle” by training the actor, a rugby player in his youth, like an athlete, allying protocols borrowed from the sports arena with his military experience and combining classic compound exercises with drills specifically devised for the scenes in question. So Bond climbing over a fence and landing in sand while chasing freerunner Sébastian Foucan’s bombmaker Mollaka through a construction site became pull-ups, box jumps and sprints.

“Organic” action - seeing things done on camera “for real” and only using visual effects to enhance them - was the flavour of the month, says Ben Cooke, a British-born, New Zealand-raised stunt performer, coordinator and director who body-doubled Craig on his first three Bond films. Also a frequent body double for Jason Statham, and something of a double-act with Waterson (at the time of speaking, they’re working together again on Jurassic World 3: Dominion), Cooke jokes that he was “006-and-a-half” and has a cameo in Casino Royale as the MI6 agent who tasers suspected double-crosser Mathis.

A term that, like Cooke, still gets thrown about today, organic action was, he says, one of Casino Royale’s “major successes”. He shot the bruising pre-credits bathroom fight in London then flew to the Bahamas for the spectacular construction site parkour, which took six weeks to film. The guy who was supposed to do the vertiginous crane-to-crane jump got injured in rehearsal, so the job fell to Cooke, with no more time left to rehearse. He did two takes; on the second, the helicopter camera jammed and had to be reset. The resulting delay stood alone atop the crane, looking down and speculating about his safety wire’s strength, was “the longest 15 minutes of my life”. There was also a 38cm by 71cm landing platform, digitally removed later, but still: “It was quite major.”

Cooke also doubled Craig for the digger-to-train jump on Skyfall, which was supposed to be on wires but, due to time pressures, he performed untethered. Over his career, Cooke has broken his hands multiple times and an ankle, undergone knee surgeries and accumulated general wear and tear, but he’s managed to avoid serious injury on Bond films. They do put you “through the ringer” though: “It’s tough, and it’s tough for Daniel.”

Craig’s Bond injury history includes eight stitches in his face after being kicked, bruising his ribs and tearing his shoulder, an old wound that necessitated six metal pins - all on 2008’s Quantum Of Solace, which also claimed the tip - well, the pad - of his fourth finger on his right hand. On Casino Royale, a fight knocked out two of his teeth. On 2015’s Spectre, former wrestler Dave Bautista’s Mr Hinx sprained Craig’s knee throwing him against a wall; filming continued around the injury but later shut down for two weeks while he underwent surgery that restricted him from running, and the pre-credits sequence had to be rejigged so Bond walked in pursuit of his quarry (because police were watching). On No Time To Die, Craig fractured his left ankle, which forced him to take a fortnight off filming. Despite that, he was back in the gym the next week wearing an Aircast.

Recovery is “the most important part” of a leading man’s regime, says Waterson, who will proactively take advantage of, say, a ten-minute break in filming to massage a calf so he doesn’t have to tack an hour of bodywork onto the end of what is already a 12-hour day for Craig. Although reports that the actor worked out for 12 hours a day for No Time To Die were greatly exaggerated. “That’s, what, the equivalent of four marathons,” laughs Waterson.

Pre-production for an actor is a bit like pre-season for a footballer: all about getting fit. But once “the season” starts, staying fit, AKA recovery, is the name of the game. Filming is an endurance test: 12 hours a day, five or six days a week, for six or seven months. “It’s brutal,” says Waterson - and he’s ex-military. He welcomes technical faults as a chance to get Craig back to his trailer, fuel him up and stretch him out. Waterson always has “eyes on” in case Craig forgets to eat, feeding him an anti-inflammatory, probiotic diet (turmeric, ginger, kimchi) and tweaking his macros daily: more carbs for energy if the shooting schedule is action-packed, more protein for recovery if it’s dialogue-heavy.

The prep required to get through all that in one piece (or not) is, says Waterson, “absolutely insane”. And you can’t act being in shape, aesthetically or otherwise: “You can only be that.” While the audience only sees actors performing action scenes once, filming is a marathon of sprints, like an athletic event held multiple times a day for two weeks in conditions and clothing that aren’t exactly conducive to sporting performance. “You try sprinting down Westminster in a suit,” says Waterson. “You’re not getting high knee lift.” He’ll train clients in ankle weights or weighted jackets to mimic awkward costumes.

Aesthetic shape, says Waterson, is “just a byproduct” of great athletic performance - a happy accident like Casino Royale’s now iconic emerging-from-the-sea scene, which Craig later said was unintentional, caused by an awkwardly sited sand bank. “It wasn’t completely conscious that he was going to look like that,” says Waterson. “But the way it was going, and the way he was transforming - I didn’t have to tweak that much.”

The aesthetic also has to be “relevant” to the character. There’s a perceptible physical progression, says Waterson, from the “blunt instrument” of Casino Royale to sharper and more refined in Quantum of Solace to the low point of Skyfall and back up. Bond can’t be down and out at a beach bar looking like he’s been slamming protein shakes, or emerge from the sea like he couldn’t hurt a fly. As loath to come over all “creative trainer” as Waterson is, “you have to be such an artist with the way you’re painting that physique”.

Craig’s body is “a product of the increasing physical demands of the role”, says Dr Lisa Funnell, an associate professor in the Women and Gender Studies Department at the University of Oklahoma, and a bona fide 007 academic. Thus Craig aligns more with “hard-body models of masculinity” popularised by Hollywood, where standards for leading men have changed over time. It’s no longer sufficient to merely look buff, as was acceptable for Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone in the Eighties. Contemporary action heroes must perform “feats of physical strength and endurance as well as complex fight choreography”. So they have to build “a fit body”, a process that, in a happy accident, provides material for promotional purposes (such as magazine profiles).

A “guarantee of the real”, the now standard-practice action-film body transformation telegraphs the actor’s commitment to the role, says Dr Funnell: “As I tell my students, if you can see their face, they’re doing the actions; if you can't, it’s a stunt double.”

In her 2017 book Geographies, Genders and Geopolitics of James Bond, Dr Funnell writes that the Bond films have transitioned from spy thriller to action, which is a “body-focused genre”. And in her 2011 essay “I Know Where You Keep Your Gun” (Moore-style eyebrow raise), she provocatively suggests that 007 has, with Craig, transitioned to a “Bond-Bond girl hybrid”. Her hypothesis is supported by Eva Green, Vesper Lynd in Casino Royale, who replied to a Guardian interviewer’s question about Craig’s “bigger boobs”: “Well, he’s the Bond girl, not me. He’s the one who comes out of the sea with his top off.” (And, as Dr Funnell points out, it happens not once but twice.)

Craig’s Bond is “physical, heroic and thus masculine while engaged in action”, Dr Funnell writes, but he’s “feminised… relative to the gaze through the passive positioning of his exposed muscular body in scenes where he is disengaged from action”. In other words, the camera loves him - a profound shift from the “British lover” heroic tradition of the franchise’s roots to the (male) body-centred Hollywood model. Note, as Dr Funnell does, how Bond disengages from, ahem, action with Solange, who opens his shirt and kisses from his pecs down to his abs. In a reversal of roles, Solange remains clothed.

By comparison with Craig’s Bond, Brosnan’s seems almost quaintly slim. But, says Dr Funnell, he coincided with a “softening of the hard body” in the Nineties, a transitional moment when Hollywood tried to reconcile muscularity with intelligence and emotion after the brawny, brainless Eighties, variously interpreted as: a manifestation of Reaganite political ideals (eg strength, discipline, hard work); a product of the growing fitness industry and commodification of the male body; a crisis of masculinity (men who no longer need strength to survive asserting their manliness); and a backlash against feminism. The shrinking male heroes “opened up space” for more female action leads.

Even Arnie lost some gains in the Nineties as the tide turned to slimmer, younger and more uncertain leading men: Leonardo DiCaprio in 1997’s Titanic, Ben Affleck in 1998’s Armageddon (symbolically replacing Bruce Willis) and Keanu Reeves in 1999’s The Matrix. With an eye on the Asian market, Hollywood also took its lead(s) from Hong Kong martial arts films, which prized skill and speed over size, and stunts over effects.

Michelle Yeoh’s Wai Lin in Tomorrow Never Dies was prompted by the exploits of Jackie Chan, Jet Li and Chow-Yun Fat, just as 1974’s The Man With The Golden Gun tried to capitalise on the martial arts craze ignited by Bruce Lee. He’d borrowed from Bond for 1973’s Enter The Dragon (a spy infiltrates a Dr No-style villain’s island lair) and he was due to discuss making a film with former 007 George Lazenby over dinner the day he died.

Brosnan is, adds Dr Funnell, a “more active” Bond than Moore and even Connery, and “frequently depicted in motion” as in GoldenEye’s run-and-dam-bungee-jump pre-credits sequence - although that’s actually a stuntman, which is why you don’t see his face. But still, Brosnan is “a good cinematic runner” like Tom Cruise, who with 1996’s Mission: Impossible surfed the wave of spymania that followed GoldenEye as the original Sixties TV series had Goldfinger four decades earlier. And Brosnan’s fights, like the satellite dish showdown with Sean Bean’s rogue agent Alec Trevelyan, also cover more ground.

Brosnan’s slenderness reflects, says Dr Funnell, “the endurance aspect” of his action scenes. In GoldenEye, those were inspired by ante-upping contemporary blockbusters such as 1994 Arnie vehicle True Lies, itself inspired heavily by Bond (the tux-under- wetsuit is a direct lift) but with double the budget of any 007 film to that point. (The set pieces and one-liners of early-career Arnie, such as 1985’s Commando, are Bond on steroids.)

Brosnan’s Bond debut was duly delayed in order to dial up the action with the dam bungee jump (which broke the from-a-fixed-point world record) and the driving a motorbike off a cliff after a falling plane (which the intrepid stunt team tried to really do before resorting to effects). Dr Funnell compares Brosnan to a football (soccer) player, built for stamina, versus an American football player, built for contact - sports that have strongly influenced both territories’ respective masculine ideals.

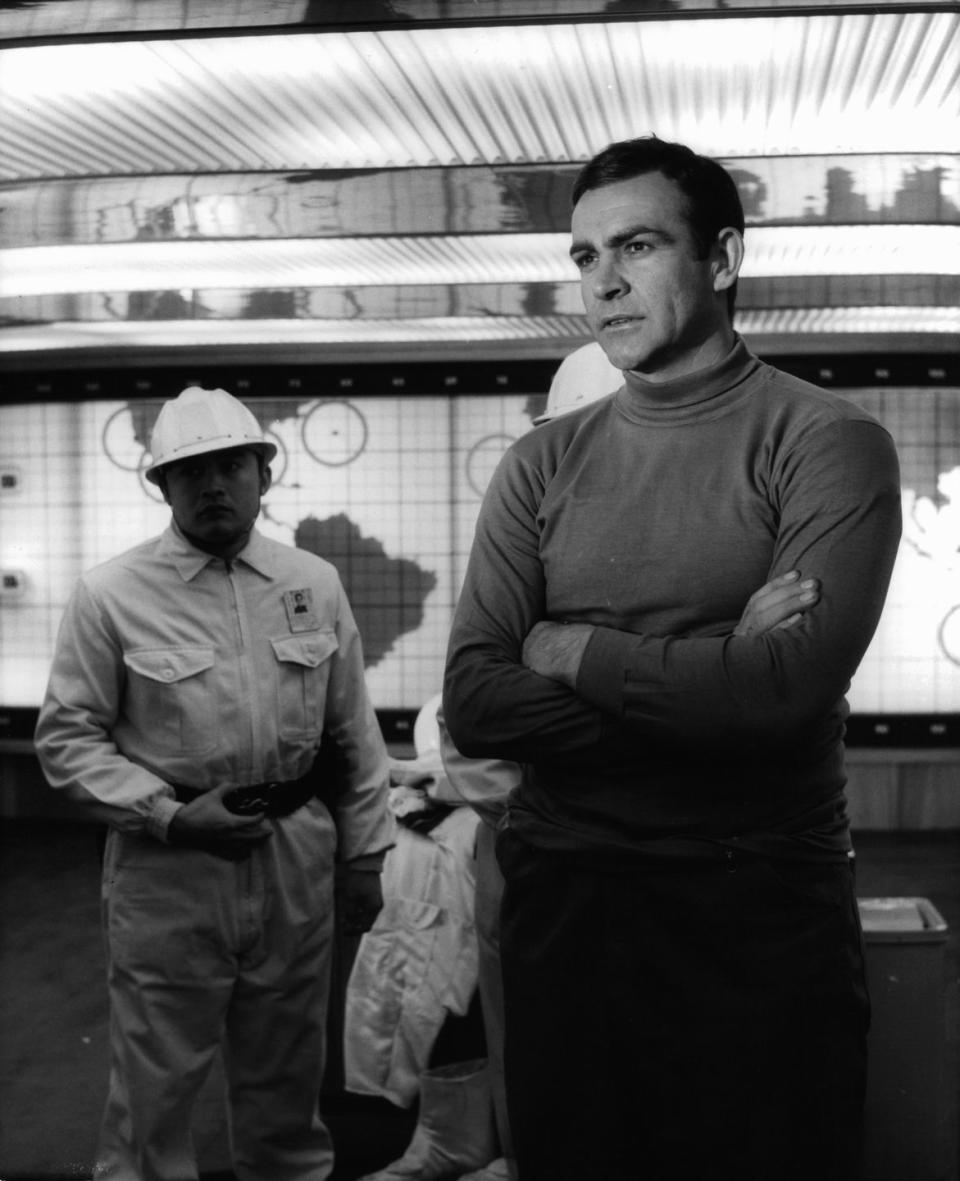

To better appeal to American cinemagoers, and create a more “mid-Atlantic”, less overtly British image for their principal, original Bond film producers Albert “Cubby” Broccoli (father of Barbara) and Harry Salzman cast Sean Connery, then 32, in 1962’s Dr No. Ian Fleming wanted an English gentleman such as David Niven for his public school-educated hero and initially dismissed the Scot as “an overgrown stuntman”.

But Broccoli, astutely, felt Niven (who would play Bond in 1967’s non-canon, utterly nonsensical Casino Royale) wasn’t tough enough, whereas Connery was “tall, with a strong physical presence… and just the right hint of threat”. When LA mafia enforcer Johnny Stompanato was fatally stabbed at the Beverly Hills home of his girlfriend Lana Turner, allegedly by her teenage daughter, his boss Mickey Cohen suspected Connery. Legend has it the man who would be Bond disarmed and decked a gun-toting Stompanato when he turned up on the set of 1958’s Another Time, Another Place, convinced co-stars Connery and Turner were entangling for real. In Hollywood at the time of Stompanato’s death and forced to lie low, Connery looked like he could kill somebody.

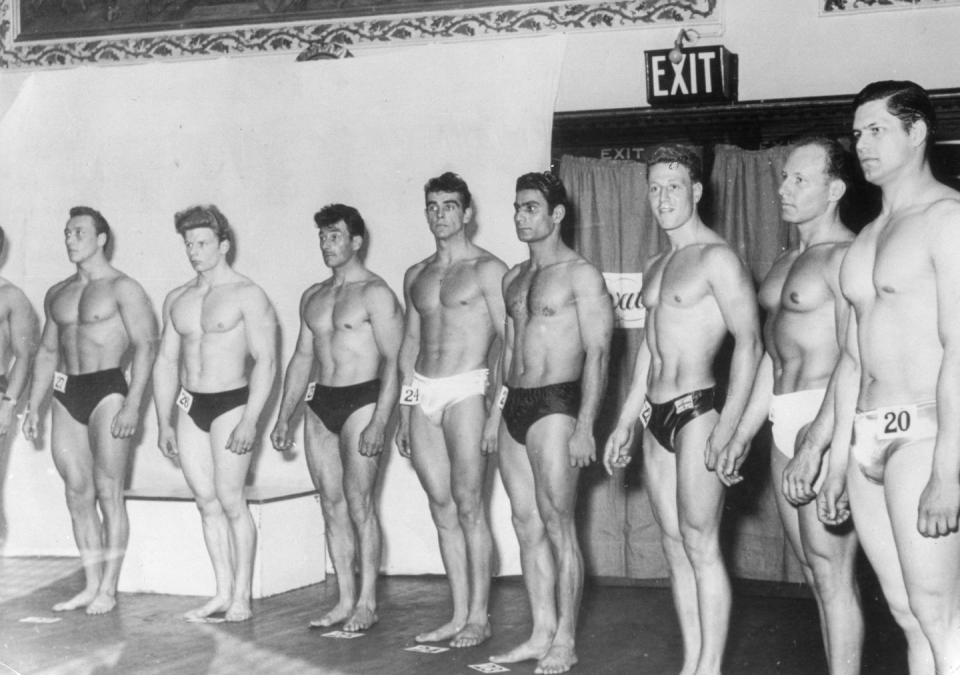

The young Thomas Sean Connery - known as “Big Tam” - filled out his 6’2” frame by joining the Dunedin Amateur Weightlifting Club in Edinburgh to look good for the girls. “Tom Connery” graced the inside front cover of Health and Strength magazine and entered the London heats of the 1953 Mr Universe contest, where he won bronze in the tall men’s class. By the time of Dr No, Connery was far from contest condition, and even then, he’d been noticeably taller and leaner than his rivals. He was no Arnie. But for the time, he was fit and athletic, with a CV that included life and underwear modelling.

“These days, when every bit-part actor over the age of thirteen has his packs and pecs and his 24/7 personal trainer, we are apt to forget that half a century ago a muscle-bound actor was a rarity,” writes Christopher Bray in his aptly titled biography of Connery, The Measure of a Man. “Nor does that age’s definition of muscularity chime with our own.”

Observing that Connery “spends more time near-naked in Bonds than any mainstream actor since those who played Tarzan” and, as the subject of “the gaze”, unfailingly elicits a reaction shot from the women he meets, Bray parallels the prototype 007’s classical proportions with those symbols of masculine physical perfection, Michelangelo’s David and Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. He also likens Connery more to Burt Lancaster rather than, as Clive James memorably dubbed Arnie, “a brown condom full of walnuts”.

Seemingly lengthened by lifting rather than tightened, Connery blamed his bodybuilding shortcomings on his refusal to take steroids or give up his beloved football. Playing a match in Manchester with the cast of South Pacific, for which he’d auditioned with two of his fellow Mr Universe competitors, he was scouted by Manchester United but turned down a trial at Old Trafford because he was sceptical of football’s long-term career prospects. During the filming of 1963’s From Russia With Love, he was challenged to a race by co-star Robert Shaw, who trained for it even more furiously than he already had to play assassin Red Grant and turned up to compete in specialist running shoes. Connery nonchalantly rocked up in boots more suited to the flinty track and won.

While Dr No’s action scenes “elevated it far above the standard thrillers of the time”, as the book James Bond: The Legacy documents, From Russia With Love spawned the action genre. Before then, only war films boasted as much action, and nowhere near as much fun. And whereas scope and spectacle traditionally slowed down proceedings, From Russia With Love’s innovative, fast-paced cutting (by editor Peter Hunt) dispensed with traditional continuity in favour of emphasising movement. Connery’s aesthetic and athleticism made him “the perfect protagonist”.

By 1967’s You Only Live Twice, even Connery’s stamina was running out. “I think one’s got to have the constitution of a rugby player to get through all the 19-week shooting,” said the actor, who later successfully sued a French newspaper for alleging that he lost the Bond gig because of weight gain. But Lois Maxwell, the original Moneypenny, told critic Roger Ebert during filming, “I think he’s trying to eat his way out of the role.”

Connery’s eventual successor, Lazenby, could’ve been his body double - in the early Bond films. (Expensive underwater footage for 1983’s non-canon Never Say Never Again, for which Connery was trained by one Steven Seagal, had to be reshot after a body double was miscast using a reference from 1965’s Thunderball.) Looking the part before he got it, Lazenby turned up to the Bond producers’ offices wearing one of his predecessor’s rejected suits (by tailor Anthony Sinclair). And Bray admits it’s hard to imagine that era’s Connery looking as “magnificent” in a snug ski suit in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service as Lazenby, who cuts an “even more lithe figure” than the former in Dr No. Director Steven Soderbergh hailed Lazenby’s “genuine presence and great physicality”.

An apprentice car mechanic turned salesman, Lazenby relocated to the UK where his 6’2” frame and sheer virility caught the eye of a photographer in a showroom. Soon he was a top male model and proud owner of his own Aston Martin. The best shot in the Australian army and a crack darts player (at least by his own account in Some Kind of Hero), Lazenby had grown up in rural Oz where “even your best friend would fight you on a Friday night” and, unaccustomed to stage fighting, bloodied the nose of stuntman Yuri Borienko, who would play leading henchman Grunther, in a screen test. The pre-credits beach fight of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service ably showcased the uppercuts and upper body of the wet tux shirt-wearing new Bond, who made a physical first impression and did his own stunts, though the insurance company prohibited him from skiing.

After Lazenby declined to return, seeing in films such as Easy Rider the end of the road for the straight-laced Bond, muscular American actor John Gavin was announced in 1971 as his successor - and had to be paid in full after the studio vetoed him in favour of Connery, a safe bet if big (financially). Cubby Broccoli insisted the “mature” Connery, only 40 but appearing much older, looked “great... better than he’s ever looked”, but his majestic physical prime was evidently not everlasting. The lighter, practically self-parodic tone of Diamonds Are Forever deliberately departed from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, which ends on the downer of Bond cradling his dead wife, and the realistic violence of contemporary movies, in order to (fairly shamelessly) appeal to a wide audience.

Then came Roger Moore. Dismissed as too young and “pretty” for Bond in Dr No, even though he was three years older than Connery, and already 43 when cast in 1973’s Live And Let Die, the actor was a conscious move away from the violence of real life, particularly terrorism. A chubby child, Moore developed his sense of humour as a defence mechanism. The Bond producers expressed concerns about his weight, forcing him to swap his customary good living for “a strict diet”. Then about his lack of condition, obliging him to start “a tough fitness regime”. Then about his hair being too long. He retorted, “Why didn’t you just cast a thin, fit, bald fellow in the first place and avoid putting me through this hell?”

A self-made gourmand who resorted to taking appetite suppressants while filming The Saint, Moore hated gyms, getting up at 6am to do press-ups and sit-ups at home “purely to make sure I got paid”. He was terrified by “bronze, topless parts”, passing over the role of Tarzan because “I didn’t think I could hold my stomach in for 26 weeks”. Asked if he did all his own stunts on Bond films, Moore quipped, “Of course! I also do all my own lying.” Still, he found the process exhausting: “If you worked a horse like that, you’d be in trouble.”

No slouch, Moore was schooled in judo, karate and boxing but relied more on his unmatched wit(s). His Bond frequently encountered overpowered adversaries who he couldn’t begin to compete with physically - like Richard Kiel’s steel-toothed Jaws, originally conceived as harder-edged but softened for laughs by Cubby Broccoli. The Bond franchise minted the action film trope of the unspeaking, unflinching, unnaturally strong henchman in 1964’s Goldfinger with Hawaiian wrestler Harold Sakata’s Oddjob. Henchmen can be stronger and more hench than Bond, but they’re never shirtless in the same scene, says Dr Funnell, not inviting direct comparison. Nor are they shown in sexual encounters with women, thus not threatening his “phallic masculinity”. Indeed, henchmen tend to be portrayed as asexual or homosexual.

There’s a sense the “freakish” henchmen are “somehow cheating”, as Dr Funnell writes in Geographies, Genders and Geopolitics, and their “bodily excesses and detriments” often prove their downfall. Whereas Bond’s body is “the ideal of masculinity”. Villains are invariably older and fatter, if not deformed or physically impaired - a portrayal of disability that, like the presentation of “aberrant” sexuality, is deeply problematic, says Dr Funnell: “Thus, film conveys powerful messages of what and who are valued in society.” Those exceptional villains capable of taking on Bond mano-a-mano include the facially scarred Alec Trevelyan in GoldenEye and Christopher Walken’s steroid-enhanced Max Zorin in 1985’s A View to a Kill. (The latter’s creepy sparring with Grace Jones’ henchwoman Mayday was choreographed by her then boyfriend Dolph Lundgren, who has a pre-Rocky IV cameo as KGB agent Venz.)

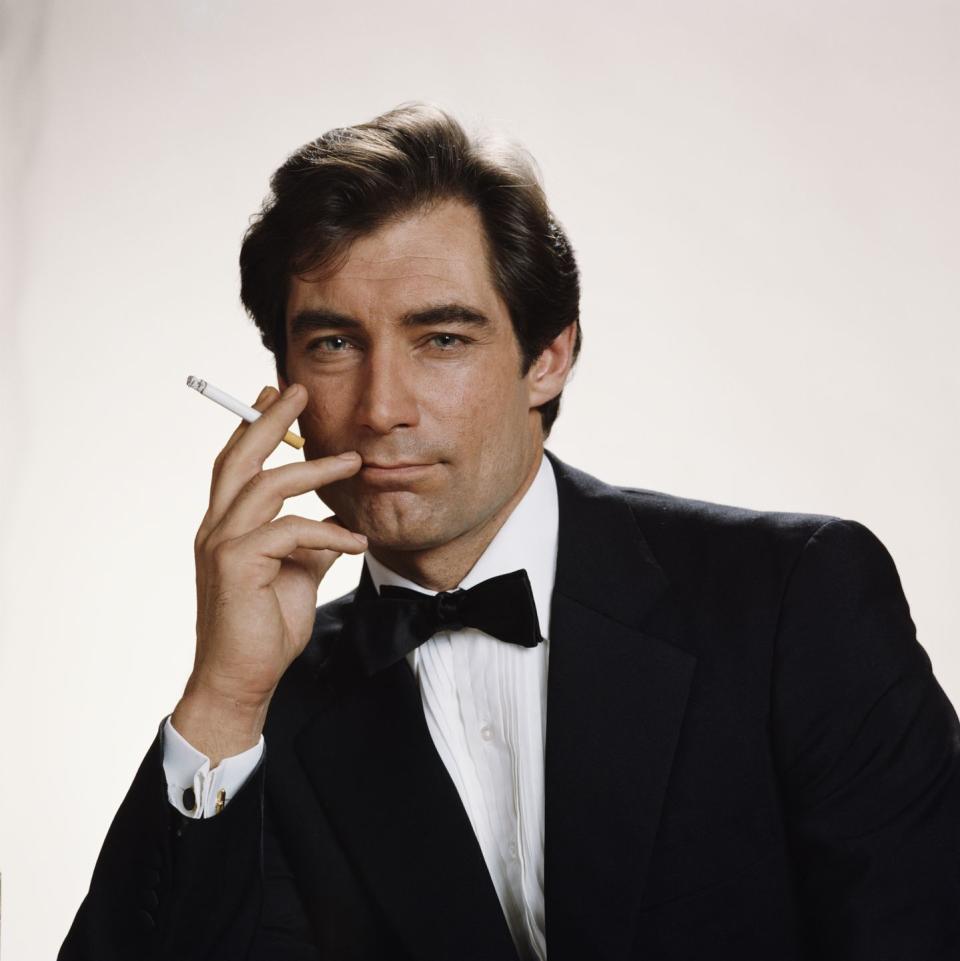

By the Eighties, Bond was under assault from another behemoth it had birthed: other franchises. The rest of the film industry had been two decades on the uptake, but Indiana Jones was envisioned by George Lucas as sustaining a series of films like Bond: 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark borrowed the pre-credits sequence, while 1989’s Last Crusade symbolically cast Sean Connery as Indy’s father; Superman II also landed in 1981. Fierce competition from Last Crusade, Lethal Weapon 2 and Batman contributed to the lacklustre box office of Licence to Kill that did for Timothy Dalton, along with the stronger violence - provoked by the Lethal Weapon and Die Hard franchises - that earned the Bond franchise’s first 15 certificate in the UK and PG-13 in the US.

Unlike Moore, criticised for his reliance on doubles, Dalton did do his own stunts. Cast at 41 after several near-misses with the role, he gamely clung to the roof of a Jeep hurtling down the Rock of Gibraltar in the pre-credits sequence of 1987’s The Living Daylights - without a wire. “It’s a matter of being convincing,” Dalton said during filming. “People want to see that it really is me jumping across rooftops or hanging off cliffs - it’s all part of the Bond image, and I don’t think you should shortchange it.”

Dalton resembled Fleming’s Bond physically and otherwise. ''Actually, I think I'm in surprisingly good shape for someone who smokes like a chimney, enjoys a drink and refuses to go to the gym,” he said. “At least in those respects I live the Bond image.” Employing “brains and ingenuity” as much as as his fists, as distinct from an Arnie or Sly, Bond would “never, never” spend hours pumping iron, said Dalton: “You're far more likely to find him in a casino or at his club with a stiff Scotch in his hand - none of this carrot juice nonsense.”

“Bond used to do ten press-ups and smoke 50 cigarettes and drink a bottle of something and pop a pill,” said Daniel Craig. “It doesn’t sound very Bond-like to talk about fitness regimes.” This was 2008, by which point he was probably already tired of talking about fitness regimes.

It’s true that Fleming neglects to detail the precise macros of his epicurean creation, who gives scant regard to wellness in the novel Casino Royale when he orders “half an avocado pear with a little French dressing” to follow his caviar, beef fillet and Béarnaise. In the novel Thunderball, Bond is dispatched by M to a health farm to subsist on soup and yoghurt after his medical report comes back showing raised blood pressure, frequent headaches and a spasming trapezius. But despite his insalubrious habits of drinking, smoking (actually 60 a day) and taking amphetamine, Fleming’s Bond is a prodigious athlete: a proficient fighter, climber, skier, swimmer and golfer (playing off a nine).

And Fleming does detail Bond’s fitness regime in the fifth novel, From Russia With Love, which is (slightly) more strenuous than Craig suggests: 20 push-ups, “lingering over each one so that his muscles had no time to rest”, followed by straight leg-lifts “until his stomach muscles screamed”, 20 toe touches, unspecified “arm and chest exercises” and “deep breathing until he was dizzy” (like his habitual cold showers, very Wim Hof).

In the third novel, Moonraker, Bond is described as “lean… lithe and brown”, and his body “healthy” in the fourth, Diamonds Are Forever. But his physical condition fluctuates: by From Russia With Love, “the blubbery arms of the soft life” have him around the neck, and in the sixth novel, Dr No, he admits, “I’m not as fit as I ought to be.”

In his 1965 critical analysis The James Bond Dossier, Kingsley Amis (who wrote the first official Bond continuation novel, 1968’s Colonel Sun, under the pseudonym Robert Markham) notes how Fleming always makes his hero undergo more intense training before undertaking a particularly arduous mission. Part of Bond’s popular appeal, Amis contends, is his essential trainability: we too could be like him “if we started the day with 20 press-ups and enough straight-leg lifts to make our stomach muscles scream”.

Now that Craig has more definitively said never again, the “next Bond” rumour mill has also been re-energised. But, even with the services of an A-list body transformation specialist, the truth is some actors “are just not capable” of doing an action film, says Waterson. He’s had conversations with producers and directors who expect their prospective leading men to suddenly acquire a 44-inch chest and 28-inch waist like they’re picking body parts out of catalogues; Waterson’s expectation-managing default response is that he’ll always maximise an actor’s genetic potential, but that varies from one individual to another. “Like with Marvel, Chris” - he doesn’t specify which - “was like, ‘Well, if I look like Daniel Craig I'm going to be fine…’ You haven’t got Daniel Craig’s genetics.”

To land Bond, says Waterson, there’s “a sliver in time” where you’ve got to be the right age and not attached to any other franchises. “Age on your side is always good,” agrees Cooke.

At the time of writing, odds have been slashed on Tom Hardy, who at 5’9” isn’t a big guy but adept at playing one, his bulk-ups the stuff of clickbait. Still, he’s already 44: hardly past it, but pushing it to crank out a couple of Bond films before he is. And although Barbara Broccoli hasn’t ruled out a black 007, age is surely the most insurmountable obstacle to Idris Elba, 49, donning the tux (currently by Tom Ford), even as a generation of actors redefine what a fiftysomething man looks like and is capable of. Statham is 54. Reeves is 57. Cruise is 59 and had a special helmet made for the HALO jump in 2018’s Mission: Impossible - Fallout so you could see it was him. Compare them to Moore, 57 in A View To A Kill, and in one unkind newspaper cartoon presented by Q with a turbo-charged wheelchair.

“What does the Bond franchise and its fandom have to say about the aging bodies of men, let alone women?” asks Dr Funnell. “Is there value in showing that a man’s physique, strength and mobility change with age, but experience and intelligence can bridge the gap?” Skyfall sort of did that, taking the injury theme further than The World Is Not Enough, with a physically diminished Bond mocked by Javier Bardem’s Silva: “Your knees must be killing you.” But by Spectre, Bond can shake off having his skull drilled.

The Bond franchise now faces its periodic identity crisis and questions over its direction and relevance, caught between a rock - the Rock - and a hard-body place. On one side, rival franchises Mission: Impossible and now John Wick, directed by Reeves’ Matrix franchise stunt double and coordinator Chad Stahelski, are pushing the boundaries of organic action ever further: Cruise’s Bond-alike in particular is giving the lie to the old axiom that nobody does it better. Cooke expects the trend for raw stunts to only get bigger, crazier, more extreme. So by that logic, the next incumbent has “got to be up for it”.

On the other side, there’s the rolling conveyor belt of comic-book films, green screen extravaganzas unbound by the laws of physics or dimensions of a dinner suit. That’s an arms race the comparatively earthbound Bond franchise can’t win - although it could have an ace up its straining sleeve in the considerable form of Henry Cavill, who lost out to Craig for Casino Royale largely because of his then too-tender age of 22. Cavill’s now 37, with his Superman gig up in the air; he’s proven he can handle action and his Man of Steel-reinforced profile could bring a younger audience to Bond who might not otherwise come without repeated insistence from their dads. (There’s also the franchise’s track record of casting actors previously considered: Moore, Dalton, Brosnan, Connery again.)

Or the Bond franchise could heed the cyclical call to “go back to Fleming” beyond just cribbing an obtuse title from an obscure short story, by transitioning generically back to spy thriller, to the vibe of the novels, their plots, even to their era. Think “007: First Class” - or, as has been mooted in the Bond community, a streaming TV series. The pay-offs: less expensive action for the producers and physical demands for the actor, who doesn’t also have to be a prodigious athlete; a more secure revenue stream with cinemas uncertain; and a Mad Men-style historical get-out clause for those problematic elements that can’t be entirely left out. (At the time of speaking, Dr Funnell is writing about sexual coercion, harassment and assault in the Fleming novels and Connery films.)

As far back as the Eighties, longtime Bond script writer Richard Maibum was complaining that breakneck action left no time for the “leisurely characterisation” afforded in the Sixties - not just in Bond but all action films. Maybe then Bond, in whatever form, could go easy on the action and bring through its secret sauce’s other key ingredients: exotic locations and escapism; vicarious eating, drinking and smoking; repartee; actual spying; character. (Ethan Hunt is such a nonentity he might as well just be called “Tom Cruise”, and John Wick is a thinly sketched excuse for awesome fight scenes.)

It’s an idea, certainly. But while Barbara Broccoli has said that the character will inevitably have to be “reimagined” post-Craig, the Bond films are a time-honoured, tried-and-tested recipe, for better or worse. It’s hard to imagine action being reduced too much, or the producers servicing Fleming purists over catering for a wide, ideally cinema-going audience. So a functionally fit body will likely be just as vital to the continued longevity of the franchise and whoever is chosen to carry it, if not more so.

Right now, film conveys powerfully that fitness, health (with or without quote marks), have never been more valued in society. In both films and novels, Bond has always reflected men’s fantasies, including physically, and men, for better or worse, have never been more preoccupied with what’s in the mirror, or prone to take a “swelfie”. The seventh 007 won’t just have to look good in a tux (whatever the label), but also out of it.

You Might Also Like