The Eiffel tower was at the cutting edge of modernity – no wonder the French hated it

Anyone watching Martin Bourboulon’s film Eiffel, about the eponymous builder of the great Parisian tower, and who knows the slightest historical background to its construction, will wonder what on earth went wrong. The great story of Gustave Eiffel – one of the foremost Frenchmen of his generation and one of the world’s great engineers – and the public response to his tower ought to provide quite enough material for a great cinematic feature, without having to resort to invention. However, that is exactly what the script by Caroline Bongrand does, assuming the audience is so thick that without a ridiculous romantic sub-plot it could not become interested in Eiffel at all.

Intelligent viewers must, if they embark on it expecting an honest account of Eiffel’s life, feel cheated and insulted. It is an enormous missed opportunity for the French cinema, because Eiffel’s life was entirely remarkable, and they should extol it and not trivialise it.

He was nothing like the flamboyant, brooding artist – a sort of Rodin in iron and steel – whom Romain Duris plays with great verve in this film. He was a serious, dedicated engineer and entrepreneur who ended up being one of the greatest men in French history.

Eiffel’s architectural legacy is spread across Europe, from the great railway bridge on the Garonne (the only truthful aspect of the sub-plot) to the railway station in Budapest. He also built part of the Statue of Liberty, which (like the Paris tower) exists to this day largely because of the quality of Eiffel’s construction techniques.

The film leaves out Eiffel’s success as a student of the sciences which were the underpinning of his success as an engineer. He fell into that profession almost by accident when in the mid 1850s the leading French railway engineer Charles Nepveu took him on as his private secretary.

Recognising his protégé’s interest and talent, Nepveu had him design a short iron bridge for a railway; before long Nepveu was bought out by the Compagnie Belge, a larger concern, and he was able to appoint Eiffel to head its the research department. The Garonne bridge project, his first major design, came soon afterwards in 1857, and Eiffel ended up in charge of it, and the Compagnie Belge’s chief engineer, at the age of 28.

Over the next quarter-century both his professional and private life expanded greatly. He built more bridges, then railway stations, and finally railway locomotives, the building of 33 of which he oversaw for Egyptian railways. Remarkably, he also designed a prefabricated steel cathedral to be shipped out like a Meccano set to Peru. All the time he was learning what cast iron and steel could accomplish architecturally, an invaluable training for what would become his greatest project.

In his private life his real love story was more remarkable than anything depicted in the film. He married Marguerite “Marie” Gaudelet in 1862, and he and his wife had five children. However, she died of tuberculosis in 1877 and he never married again – he lived until 1923. His eldest daughter Claire (played in a very underpowered part in the film by Armande Boulanger) helped bring up his children, became his secretary and, effectively, a consultant to his business.

He claimed to have been inspired by a wooden tower that was erected in New York in 1853, when Eiffel was 21, for the international exhibition there that year. However, as the film does indicate, two engineers in Eiffel’s practice, Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, actually designed the structure.

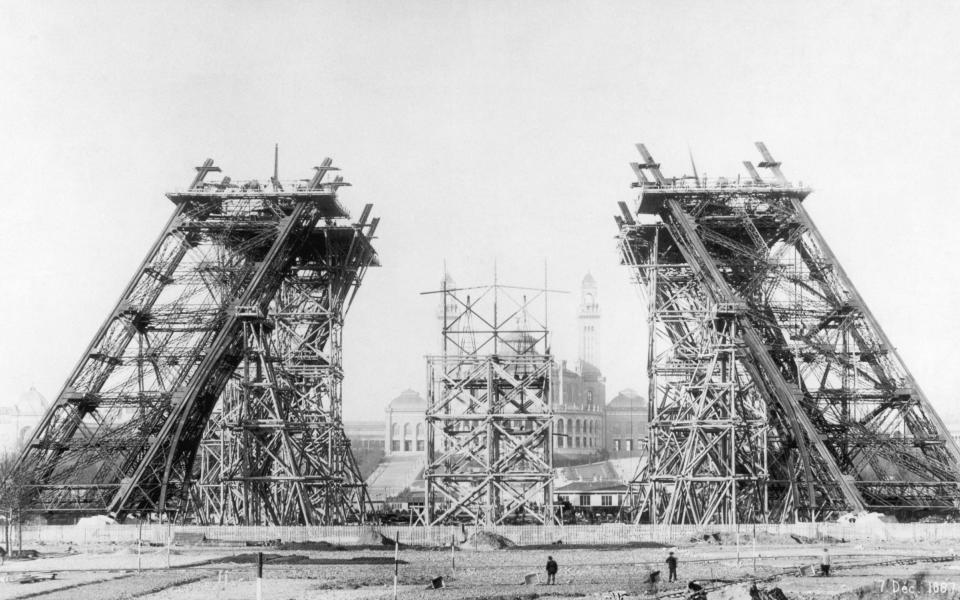

As the tower went up in 1887-89 it caused outrage among some of the most famous cultural figures in France, who felt it was desecrating Paris. Eminent figures such as Maupassant, Gounod and Massenet railed against it.

It was a radical departure not merely in design, but in the human conception of what was possible in terms of building upwards. This was more than 15 years before the first steel-framed building appeared in London, and a decade before America started the vogue for the skyscraper.

It was at the cutting edge of modernity; no wonder so many people hated it. At the end of March 1889, when it was completed, and before the lifts were put in, Eiffel himself led a party of dignitaries up the tower. Many dropped out on the way, rather nervous about being at that height. When he reached the top he planted a French flag there. What a fine scene that would make in the film, only it’s not there.

The tower was only supposed to be a temporary attraction; 133 years later, it is still there. It did not take long for Parisians to realise they had actually acquired something intensely special, and that would soon come to symbolise their city around the world. (The London Eye, supposedly temporary for the Millennium, has achieved something similar.)

It has also proved a huge earner for the French: it is the most-visited monument in the world for which one has to pay an entrance fee, with around seven million people in a normal year. In a city with a comparatively low skyline it still stands as the tallest building in Paris, whose other experiments in sky-high architecture have, rather like London’s, been poorly thought-out and rather unattractive.

It took until the late 1950s, when developers were lobbying to maximise their space by building in the sky, for Paris to contemplate another great tower: but the one that eventually arrived in 1973, Montparnasse, a symphony in reinforced concrete, is now showing its age. Just two-thirds the height of the 1,080-ft Eiffel Tower, it was then the second but is now the fourth-tallest building in the capital, after two towers at La Defense. Other towers now litter Paris’s landscape and that of its outer suburbs, and cannot be said to have improved the place.

The heaviest concentration is at La Defense, but they loom over much of the city from whatever vantage point one climbs to see them. None has the beauty or original genius of Eiffel’s tower, but then most have effectively come off a production line to provide functionality rather than to make a statement about a nation’s achievement and progress.

More new skyscrapers are planned, as Paris seeks to compete with the world’s other great cities for businesses to come in. Perhaps out there is an Eiffel waiting to do something desperately original: it will require the French profession of engineering to be superior to its present generation of film-makers.

Eiffel is in cinemas now