Driving back in time through the Algerian desert – a perfect antidote to today's climate

“Wind up your window and hold on,” says Othman, our driver. He floors the accelerator and we speed towards the dune, the vehicle suddenly rearing skyward as we hit the slope head-on. He grinds through the gears and we scale the soaring wall of sand, coming to an eventual rest on a high ridge. From there, the Grand Erg Occidental, the great Western Sand Sea, is visible in all its vastness. I step out of the car to take in the panorama. In every direction, great windswept dunes, some up to 400ft high, surge across the horizon like Atlantic rollers in a winter storm.

Othman checks the time and walks out into their midst. He bows and falls to his knees, his tiny, praying figure highlighting the sheer enormity of the terrain. This erg alone covers an area twice the size of Belgium. One of the largest sand seas in the world, it represents just a small fraction of Algeria’s share of the Sahara, which extends north to south for a thousand miles and is considered by many to be the most beautiful desert on Earth.

Othman concludes his Friday prayers and we drive to the nearby town of Timimoun, nicknamed “La Rouge” for its striking, ochre-red, mud brick architecture. “The colour not only reflects the local red rock,” he tells me. “It also represents blood; our physical sense of belonging in the desert. We feel a deep connection to it. Everyone who comes to the Sahara feels it too.” We pull up outside the police station and wait for an escort for the onward journey, a bureaucratic necessity for tourists travelling by road in much of Algeria, a country with a particular fondness for red tape.

We set off in convoy and drive 400 miles across the desert’s infinite variety of landscapes, the dunes soon giving way to gravel plains, then petrified forests, and finally, a spectacular rocky oasis, the “pentapolis” of the M’Zab Valley, a chain of five ksar, or fortified cities, more than a thousand years old. First established by the Mozabites, a conservative Muslim sect, each of the ancient settlements is dominated by a mosque and minaret-cum-watchtower. Box-like houses spill down the surrounding hillsides, their roof terraces painted pastel blue – a centuries-old method for repelling mosquitoes.

Similar in appearance, they are unique in atmosphere. Ghardaia is the valley’s commercial hub, with a lively, welcoming souk that sells everything from herbal haemorrhoid cures to great branches of sticky, sugary dates. El Atteuf is the oldest; its minimalist mosque was much admired by the legendary Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, and is said to have inspired his designs for the Notre Dame chapel in Ronchamp. Beni Isguen remains the most traditional. Here, visitors can only enter the historic centre accompanied by a local, and entry times are restricted to after the Asr, the midafternoon prayer. Smoking, revealing clothes and the taking of selfies are all frowned upon.

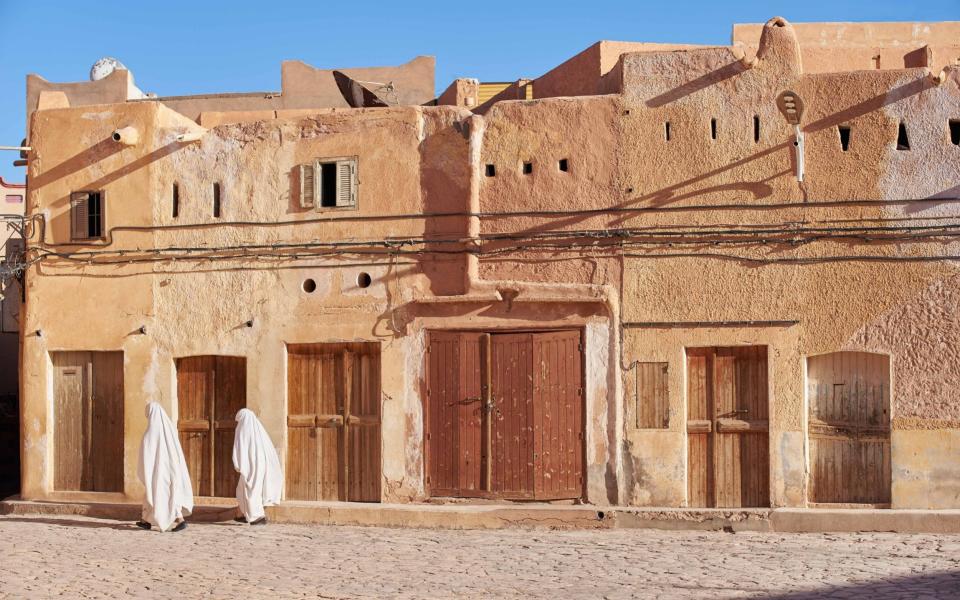

“Visitors are very welcome,” says Khaled, my guide, “but we ask that they respect our way of life.” With a smile, he then adds: “It is our home after all, not just a backdrop to an Instagram post.” We wander the timeless, atmospheric streets, originally built wide enough to accommodate two passing camels. As we near the hilltop, a group of women glide past wearing the traditional haik, a ghostly white shroud. “Young girls are allowed to show their faces in public,” explains Khaled, “but after marriage the custom is to wear the haik tightly around the face, so that it reveals only a single eye.”

We climb to the rooftop of the minaret and look out across the ksar to its grove of 10,000 palm trees. There, life is equally traditional and subject to its own set of strict rules. A council of men oversee the palmeraie’s 600-year-old irrigation system and penalise those that take more than their fair share of water. The palms, known locally as “holy trees”, are considered so precious that cutting one down is deemed sinful.

“The world is changing fast and losing much in the process, but not here,” says Khaled. “We’ve managed to survive in the harsh desert and hold on to our traditions for more than a millennium. We do all we can to preserve our beautiful way of life because it is unique, not just in Algeria, but the world.”

In the morning, I take the short flight south to Illizi for the last leg of the journey. Waiting for me in a four-wheel drive is Tito, an imposing figure who sports the traditional taguelmoust, the indigo turban that serves as both desert protection and a symbol of Tuareg identity. We head for the volcanic plateau of Tassili n’Ajjer on tarmac buckled by the 50C (122F) heat of summer. Signs warn of deadly curves and dangerous stray camels, but Tito picks up speed, undaunted.

“If you love the desert, the desert will be kind to you. So never fear it,” he says, as we veer off-road, bouncing over a dry lake bed to a mixtape of North African desert blues. The mobile signal disappears and a satellite phone becomes our only link with the outside world. We carry no maps, for Tito navigates on instinct alone. “A Tuareg proverb goes: ‘We are born with sand in our eyes’,” he tells me. “It means we have an ability to read the desert like a sixth sense. Information is passed down genetically from our nomadic forefathers, so a memory and understanding of the land is imprinted on us from birth. It’s like an internal satnav.”

In the lee of a sand dune 2,000ft high we set up camp for the night. Tents are pitched, a fire is lit, and the important ritual of tea making gets under way. “Tea is to the Tuareg, as wine is to the French,” says Tito while filling a teapot with leaves, sugar and water, then placing it among the glowing embers. “It’s said that the first boiling tastes ‘bitter like life’,” he continues, pouring the brew from a height into cups before returning it to the pot to heat again. By the second boiling and aeration he tells me it is “considered as sweet as love”. After a third, it’s “as light as the breath of death” and ready to drink with the requisite head of sugary foam. “Tea without froth is like a Tuareg without their turban,” he adds.

We wake at sunrise and set out along an oued, a dry riverbed, deep into the heart of Tassili n’Ajjer, a vast national park and Unesco World Heritage Site that covers almost 30,000 square miles. At every turn, there are great cathedrals of rock sculpted into other-worldly formations by nature. And as time passes, every viewpoint becomes more astonishing than the last.

One afternoon we arrive on a great lunar plain dotted with mesas and buttes that lie marooned in multi-hued waves of sand. On another, we drive along a 15-mile gorge, its towering cliffs weathered into pyramids, pinnacles and chimney stacks. Human forms are discernible in the rock, too. It’s akin to driving along the grand avenue of a fallen civilisation – their monuments left abandoned and crumbling. We have all this heart-stopping scenery to ourselves. There are no other tourists; our only company is an occasional eagle wheeling overhead. Yet, incredibly, this desolate land was once teeming with life.

“The Sahara was fertile savannah, abundant in wildlife,” says Tito, as we scramble to the back of a cave. He points to a pictograph capturing the thrill of the hunt: a band of men brandishing spears and chasing down a herd of antelope, painted in a mixture of blood, milk and powdered rock. “We know from the rock art that 12,000 years ago there were all kinds of animals: elephants, crocodiles, lions and rhinoceroses,” he says. “Four thousand years later, the desert dwellers painted the giraffes they domesticated and the cattle they farmed. And as the land became drier, around 3,000 years ago, they made carvings of the camels that passed through on the trans-Saharan caravans. So the images are more than art, they are encyclopedia and history books, too.”

Over the course of a week, we edge slowly south, with occasional stops for tea to dig ourselves out of the sand or collect water from gueltas, the desert’s hidden pockets of water. By night, we warm ourselves on bowls of couscous and cumin-spiced soup under starry skies so bright there is little need for a head torch.

We finally reach our journey’s end close to the frontier with Libya, where the desert drifts through the most startling spectrum of colours I’ve ever seen: from gold to orange then deep Martian-red. The rock art becomes more delicate and detailed, too. There are extraordinary scenes of prehistoric daily life: a human figure milking a giraffe, a couple engaged in an erotic encounter, and a man fighting off a charging elephant with a boomerang. They make up more than 15,000 works found within Tassili n’Ajjer’s borders, forming one of the richest collections of rock art in the world.

“The desert was so rich in prey it gave those early inhabitants free time for self-reflection, for learning, and for creative expression,” says Tito. “Thousands of years later, the calm and the peace of the desert still allows us time to stop and think. It is so vast and ancient, it teaches us that our place in the world is small, and our time here passes quickly. It reminds us that we live in a world of great wonders, and our souls are enriched when we seek those wonders out.”

How to do it

Simon Urwin travelled with Untamed Borders (01304 262002; untamedborders.com) which will launch bespoke tours of the Algerian Sahara in October 2021 from £2,300pp. Fixed-date group trips, commence in January 2022 from £1,675pp.

Overseas travel is currently banned with limited exceptions. For further details, check gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/algeria