‘Don’t mention the election’ appears to be the recommendation in my French village

When I lived in London, my dinner table was often the scene of heated political arguments, so much so that we instigated the Wooden Spoon Club, for those who liked to stir the pot. On some occasions, the spoons were real, bashed loudly on the table with shouts of “Order! Order!” as everyone competed to have their say. The longer the evening went on, the more wine drunk, the louder those conversations became.

In my 20s, I remember having long discussions over slowly-sipped coffees or glasses of rough red in cafés in Paris with other students. It was the 1980s and I was then an earnest sort. Discussing the minutiae of Jacques Delors’s relationship with Margaret Thatcher was the closest I got to flirting.

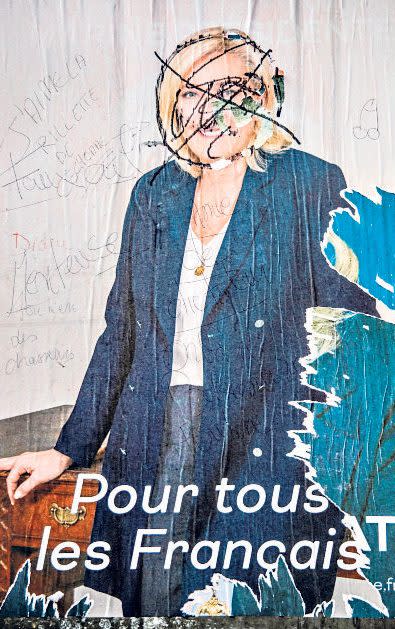

So when we moved to France and the presidential election rolled around, I was looking forward to more of the same. The noticeboards by the recycling bins were regularly pasted and repasted with posters. Far-right candidate Eric Zemmour’s eyes were often coloured in with red pen. The edges of Emmanuel Macron’s posters soon became ripped at the edges as unknown hands attempted to remove them. In a political graffiti classic, Marine Le Pen’s face was Sharpie’d with a little black moustache. As the first round of voting approached, posters of all 12 candidates were displayed along the railings in front of the town hall. It all looked quite cheerful in the Mediterranean sunshine, a sort of lively political bunting.

But where were the conversations? Eavesdropping in the bars and restaurants, I heard people discussing the warp and weft of ordinary life: children, friends, neighbourhood gossip, prices in the supermarket, traffic, parking, weather, oyster prices (fine, that might be specific to here, but you see where I’m going).

If I tentatively asked friends about the election, worried that perhaps in doing so – like diving in for a hug – I might be committing some terrible faux pas by introducing politics to the conversation, the most common response was a grimace, an enigmatic smile, a shrug of the shoulders, a non-committal “We’ll see”. One of my friends, a supporter of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the veteran leftist and leader of La France Insoumise (France Unbowed), admitted that she’d be holding her nose and voting for Macron in the run-off. And that was as deep as it got. I saved my wooden spoons for stirring soup.

Then it occurred to me that it was entirely possible everyone was discussing politics – just not with me. And not simply because they thought my French wasn’t up to it. Just as in post-Brexit Britain some friends and families kept their relationships intact by implicitly or explicitly agreeing not to mention the B-word to forestall fallings-out that would put all future family birthdays and Christmases in jeopardy, perhaps my new neighbours were shielding me from political awkwardness.

When we moved to France last September, to this dreamy village with its pink sunrises and apricot sunsets, its harbour bobbing with boats, its lagoon full of flamingos, its skies speckled with swifts, its bakeries, vineyards, markets and church bells, there is one thing I knew for sure then, but had pushed to the back of my mind since. In the 2017 presidential election, nearly 55 per cent of the vote here went to Marine Le Pen.

Away from the smart little harbour and grand wine-makers’ houses that line the better boulevards, our village and the surrounding countryside, like many rural areas in France, has its share of poverty. People fear declining public services, faltering job prospects, the rising cost of housing, fuel and groceries. Paris feels a long way away. Neat and correct, Macron appears grand and unsympathetic. In these circumstances, it’s easy to see how, for some, Le Pen’s populist tub-thumping appeals.

And so for a variety of reasons, from politeness to embarrassment, to awkwardness, even in some cases to shame, I can see how it might be hard for some of my neighbours to look me in my newly-minted-resident face and admit they favoured Marine Le Pen, the hard-line, anti-immigrant nationalist, who, if she were ever elected, would almost certainly introduce legislation that would affect the lives of people like me.

In the run-up to the run-off, there was lots of chatter in Facebook groups for English immigrants, some of whom call themselves expats, that a Le Pen win wouldn’t affect us much at all – the subtext being that she doesn’t really mean us, we’re not brown enough. This ignores her campaign slogan, “Rendre aux français leur pays et leur argent” (Give the French back their country and their money – America First, anyone?), and her promise to give priority to French citizens for housing, jobs and welfare payments.

It is a strange and uncomfortable feeling to live in a country where I cannot vote, but an election has the potential to affect my future. Of course, almost all of my life I have known people who have been in this position. Being in this position myself now adds an element of uncertainty and fear to the empathy I previously felt.

Last Sunday, our village voted 58.63 per cent for Madame Le Pen, though our département, the Hérault, voted in Macron by a squeak, at 52.57 per cent, which reflects the votes in the more affluent areas to our north, such as Montpellier.

The election posters have come down now, the hoardings whitewashed. No doubt more advertisements will soon fill the blank space, colourful images of car rallies, brocantes, festivals and concerts. Regular life in the port de plaisance resumes. We go about our daily routines, the normal weekly round of shopping and lunches on terraces and walks by the water. People say good morning, pat the dogs. The spring season is in full swing now, with visitors arriving from all over France, from all over the world. Holiday homes are opened up. People with wheelie cases hammer code numbers into key boxes and fumble with unfamiliar locks, to open up doors to holiday weekends, weeks, months. More boats arrive each day.

While its politics may be insular, protective, wary, the village economy sails along on strangers coming each year, to buy local oysters, picpoul de Pinet, Noilly Prat vermouth. Sometimes, like us, they also buy houses, and bed down, watch closely and wait to see what comes next.