Diego Maradona Saved Paolo Sorrentino’s Life. Cinema Gave It Meaning

Diego Maradona saved Paolo Sorrentino’s life; cinema gave it meaning. On Sunday, 5 April, 1987, Maradona’s Napoli travelled to Tuscany, where they played out a goalless draw with Empoli. Sorrentino, the future maestro of Italian cinema, then a 17-year-old schoolboy, had planned to spend the weekend with his parents, at their house in the mountains. But with the World Cup-winning Argentine as their talisman, Napoli were on the way to their first-ever Serie A championship. Young Paolo, a fanatical supporter of his local team, was permitted, for the first time, to go to the match alone. Both his parents were killed that weekend, poisoned in their bed by carbon monoxide fumes from a faulty heater.

“That tragedy has marked my life,” Sorrentino told me, in September. “My adolescence ended with my parents’ death. At 17, I was as old as I am now. I’m still stuck on that date, on that day. My life has not changed. That pain is still with me and will always be with me and has forged my temperament, my personality, and made me unstable and very prone to rage. All that is connected to that tragedy.”

Also connected: Sorrentino’s choice of career. “There is a very direct cause-and-effect relationship between the deaths of my parents and my decision to become a filmmaker,” Sorrentino said, speaking through an interpreter. “That tragedy was so unbearable in terms of pain that the only solution I found was to create a parallel reality, this fictional world where I can escape and find relief. That’s why I decided to become a screenwriter and then later a filmmaker. Therapy for me was spending a lot of time describing a reality which was not perfect, but which I could tolerate, perhaps even love. My own reality, I just could not tolerate.”

Now, more than three decades after the events described, Sorrentino has made a film dealing head-on with his tortured adolescence. Set in Naples in the 1980s, The Hand of God is a gorgeous evocation of that most intoxicating of Italian cities, by turns seductive and repellent, sacred and profane. It is a tribute to a mesmerising footballer who elevated his sport, in Sorrentino’s eyes, to the level of art. It is a memorial to the director’s parents, and to a lost way of life. And it is a paean to movies as refuge from real life, a celebration of escapism. “Cinema’s not good for anything,” huffs a character in The Hand of God. “Except as a distraction from reality.” In other words, the film’s director might reply, cinema is as essential as air.

The Hand of God is a film, according to Sorrentino, “that has been on my mind forever”. The delay, clearly, is understandable. “For many years I didn’t have the courage to write it. Then I found the courage to write it but not to do it. Eventually I found the courage to do it.”

Putting the words on the page was the hardest part, harder even than filming the scene in which his parents die. “I cried most of the time during the writing,” he said. “It wasn’t easy to see the screen, it was blurred by my tears.” When the film was in production, “I did it the only way I could. That is, I pretended it was a film like any other. You somehow hide yourself behind the cinematic technique. At least, I tried.”

Sorrentino was talking to me on the terrace of the Excelsior Hotel, overlooking the sparkling Adriatic from the Venice Lido. It was morning on the first day of the Venice Film Festival, the day before The Hand of God’s premiere. The sun beat down, but a soft breeze kept temperatures in the mild mid-20s. Apart from the Covid checkpoints outside, and the bag searches at the gates, and the masked queues of festival participants waiting to show their credentials, all seemed unusually well with the world.

“Look at where we are,” said Sorrentino, drawing on a cigar and gazing, not entirely approvingly, towards the empty beach. “Cinema is a place which seems to be glamorous. But films are made by and attended by people who are very much uneasy with themselves, and with life. And I do believe that those who are at ease with themselves and with life are outside that circle.”

Sorrentino made his debut as writer-director in 2001 with a comedy, One Man Up, starring Toni Servillo, who became his enduring muse. His breakthrough came in 2004 with the crime-drama The Consequences of Love. Servillo plays an elegant, fastidious, lonely middle-aged bag man for the mob, exiled to a Swiss hotel, where he becomes infatuated with a beautiful waitress. Somehow both austere and flamboyant, cool and existential, it marked the arrival of a major talent with a baroque imagination, a high style, and cold steel in his veins. He followed it with The Family Friend (2006), another portrait of an older man, the miserly Geremia, played by Giacomo Rizzo, who is undone by his desire for a lovely young woman.

International acclaim followed in 2008 with Il Divo, Sorrentino’s scabrous biopic of the Machiavellian Italian Prime Minister, Giulio Andreotti. A stunning portrait of power corrupted, it was distinguished by another terrific performance from Toni Servillo, heavily disguised this time — concealment and surface being as central to Sorrentino’s cinema as revelation and depth. His first English-language film, This Must Be the Place (2011) was an extraordinary road movie, with Sean Penn fully committed as a zonked-out goth rock star on the trail of the Nazi who brutalised his father. If that sounds weird, that’s because it was weird: weirdly funny, weirdly charming, weirdly trance-inducing, and weirdly sui generis.

In 2013, Sorrentino delivered his masterpiece. The Great Beauty is a ravishing document of Roman decadence, with Servillo, again, as Jep, a jaded literary journalist and soi-disant king of socialites, executing a lazy front crawl through the fetid “whirlpool of the high life”.

“I was destined for sensibility,” sighs Jep, and his creator might say the same. The Great Beauty is a pungent satire of Sorrentino’s adopted home city, but it’s also a swoon, a bacchanal, a glorious debauch. The fluidity of Sorrentino’s camera, the sumptuousness of his mise-en-scène, the vulgarity, the glitz, the flash, the flesh, the tits, the ’taches, the dance numbers! Jep quotes Flaubert’s stated desire to write “a book about nothing” — all style, no substance. And there are those who suggest Sorrentino succeeded where old Gustave failed, that he is more interested in the fabric of the curtain he is pulling back, than what it reveals about the politics of the rotten society hidden behind it. He is focused on the trappings of power and money, rather than the costs and implications. But what fabric it is! And what trappings they are! Sorrentino won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and it would have been a scandal if he hadn’t.

Since then, Sorrentino aficionados have been treated to the trippy Youth (2015), with Michael Caine’s conductor and Harvey Keitel’s movie director, lions in winter, in search of their missing mojos at an exclusive Alpine spa. (Maradona makes an appearance in that film, too, played by the unimprovably named actor Roly Serrano.) The Young Pope (2016) was a sexily sacrilegious TV series, with a gleeful Jude Law relishing his role as a hardline-conservative American pontiff. Its sequel, The New Pope (2019), saw Law joined by John Malkovich, an actor whose languid cynicism seems tailor-made for Sorrentino. In 2018, Sorrentino released Loro, an epically lubricious portrait of the repulsive former Italian president, Silvio Berlusconi, yet another chewy part for the chameleonic Servillo.

Sorrentino’s films are stylish, surrealist investigations of love and regret, sex and death, age and beauty, irony and rapture. They are chic and vulgar, frivolous and profound, sublime and ridiculous. Like life, he seems to say, although life lived at a pitch many of us might occasionally struggle to recognise. His work exhibits a particular fascination with the intersections of sex, money and power. His wild shifts in tone, his images at once painterly and soft-pornographic, his strange and uncompromising vision, not all of this is to everyone’s taste — and the fact that his gaze is unblinkingly male has not gone unnoticed by feminist critics — but it’s hard to imagine anyone coming away unstimulated from a Paolo Sorrentino production.

The Hand of God might be his most satisfying work since The Great Beauty, and his most affecting. Funded by Netflix, it was shot in and around Naples in the summer of 2020, in the brief period of freedom between lockdowns. “It was almost idyllic,” Sorrentino told me. (Love that “almost”.)

As the toothsome TV pundits like to say of football matches, Sorrentino’s cinematic Bildungsroman is a game of two halves. The first half is a sensual, evocative, and very funny depiction of an awkward teenage boy’s coming of age in the considerable bosom of his loving but loopy family. (Bosoms in Sorrentino films are frequently considerable.) The second half opens with an appalling tragedy identical to that which befell Sorrentino’s parents. It becomes a sombre, ruminative, and moving meditation on love, loss, and the forming of a film director — which is what the boy aspires to be, inspired, among others, by Fellini and a more recent, real-life Neapolitan director, Antonio Capuano (played here by a gloomy Ciro Capano), as well as by the divine Diego’s example of the transcendence of the imagination: if you can dream it, you can do it.

Much of the pleasure to be taken from the opening section of The Hand of God is in the portraits of the boy’s family, the Schisas, and their eccentric friends and neighbours. We meet the boy’s father, a sweet-natured man who works in a bank and manages to be both extravagantly uxorious and habitually unfaithful. Inevitably, he is played by Toni Servillo. (Hard to imagine Servillo’s chagrin if he hadn’t been offered the part.) We meet the boy’s vivacious, prankster mother (Teresa Saponangelo) and witness her agonies over her husband’s infidelity. We spend time with his older brother (Marlon Joubert) — though not his sister because, in an enjoyable running joke, she’s always in the bathroom. All these are closely modelled on Sorrentino’s own family.

We meet, too, the Baroness (a scene-stealing Betty Pedrazzi), the family’s snobbish upstairs neighbour, grandly indignant, who will play a crucial — and unexpected — role in the boy’s sentimental education. And at an al fresco family gathering, we meet his extended family, including the monstrous Signora Gentile, seen shovelling a great ball of burrata into her gob, liquid cheese running down her chin. Perhaps most memorably we meet the boy’s crazy-beautiful Aunt Patrizia, a traumatised exhibitionist, played with wit and pathos by the striking Luisa Ranieri. “When did you all become so disappointing?” wonders a senior family member. Viewers may beg to disagree: you might not want to live with them, but they’re a lot of fun to watch.

And then we witness the deaths, and Sorrentino’s reaction to them. “In the film,” he said, “the percentage of pain and the difficulties I experienced when I was a boy is very limited, very small compared to the dark, sombre reality I found myself in. But in order to make a film, even if it’s based on a true story, you have to add novelistic and cinematic elements. What is true to my own personal story is the feeling.”

The fantastic and the quotidian coexist in The Hand of God, as in earlier films — as well as the family we encounter San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples, and the mystical Little Monk, a legendary Neapolitan sprite. But those steeped in Sorrentino, as I was in the days leading up to our interview, might detect a plainer, less ostentatious cinematic style — by his standards, at least — compared to the rich sauce of earlier works, more minestrone than ragu.

For the first time Sorrentino was working without his regular cinematographer, Luca Bigazzi, who photographed all of his previous films. For The Hand of God, Sorrentino turned instead to Daria D’Antonio, another native Neapolitan, who it is reported will be working with him on his next film, Mob Girl, starring Jennifer Lawrence as an FBI informant. (That’s if his next film isn’t a biopic of the late Hollywood super-agent Sue Mengers, also starring Jennifer Lawrence; unlike the mob girl, on this topic alone Sorrentino pleads the fifth.) Also a new production designer, Carmine Guarino, and a new costume designer, Mariano Tufano. The music is more sober, the colour palette more subdued, the camera more static; all the customary cinematic effects are stripped back.

“I do believe that each story dictates its own style,” said Sorrentino. “At the very beginning [of shooting The Hand of God] I tried a tracking shot but I realised there was something wrong with it. Yes, the story called for a simpler approach.”

I am not the first viewer to note that if The Great Beauty was, in some measure, Sorrentino’s homage to Fellini’s sumptuous La Dolce Vita, then this might be his Amarcord, Fellini’s story of his own boyhood in southern Italy, warmly comic, pointed, unsentimental. The title of Fellini’s 1973 classic, roughly translated, means “I remember.”

Almost all the action in The Hand of God is seen through the eyes of the teenage Fabio Schisa, known as Fabietto, a childhood nickname that is both fond and diminishing. This stand-in for the youthful Sorrentino is played with appealing sensitivity by newcomer Filippo Scotti, upon whose slender frame the director hangs the many separate elements that make up the film. Fabietto is a dreamy, awkward adolescent, a loner in the playground, unable to talk to girls.

He’s a bit of a geek, your Fabietto, I told Sorrentino.

“Geek?” repeated the director. “What is ‘geek’?”

He is not cool, I suggested. He is shy. He is friendless. He’s a virgin. He wears his Walkman clipped to his belt, 24/7.

“He’s a disaster!” said Sorrentino, in English.

Sitting next to Sorrentino and opposite me was Filippo Scotti. Sorrentino is 51; Scotti 30 years his junior. Both have curly hair, each wears an earring in his left lobe. Both are Italian. I could probably make more of it, but in truth there, as far as I could tell, the similarities ended.

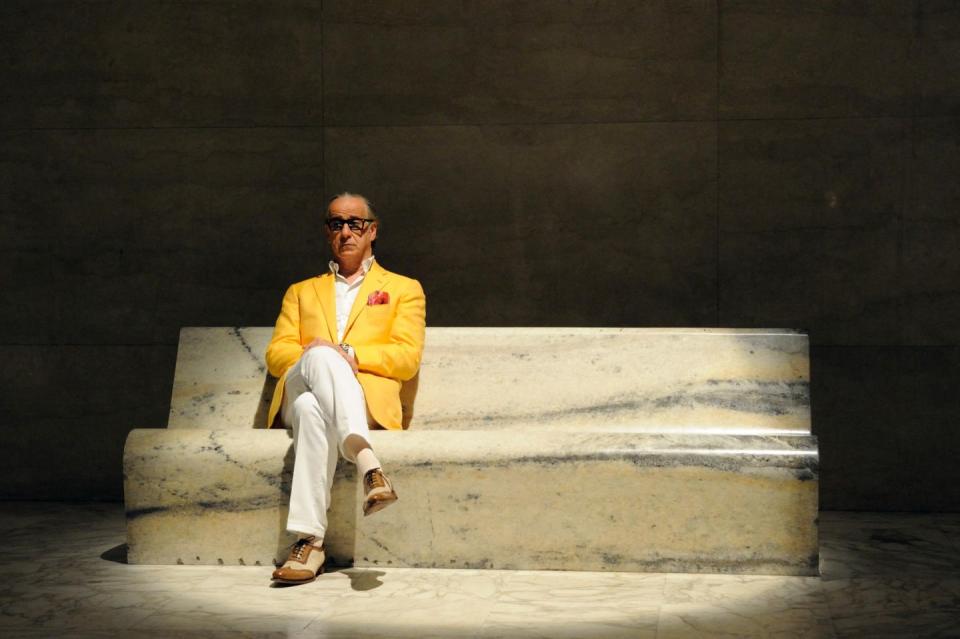

Sorrentino is something of a crumpled dandy. With his unruly corona of steel wool hair, his capacious eye bags, his wry, hangdog face, and his vintage rocker’s sideburns, he looks like a whisky priest, albeit one with a Mr Porter account. On the day I met him he wore a silk blazer the colour of sand over a deep blue chambray shirt, unbuttoned at the chest to reveal a tan of varnished mahogany.

Fresh-faced, pale and delicate, Scotti wore a black leather jacket, Prada logo on the breast pocket, over a white T-shirt. Sorrentino answered my questions expansively, in great detail, mostly in Italian but with occasional English exclamations, making points with his smouldering stogie. While he talked, Scotti sipped bottled water and waited patiently for questions addressed to him. When they came, he answered in English with a fluency impressive in one who said he only recently began to learn the language.

The affection between them was clear. It was also clear who was boss. Scotti had never been to Venice before. Quite something, I would imagine, to arrive, aged 21, in such a spectacular city for the first time to find one’s own image, on posters for The Hand of God (È Stata La Mano Di Dio), adorning cathedral-sized buildings on the Grand Canal. He looked genuinely taken aback. “It’s just amazing!” he offered, because what else can one say about such an experience? His director had seen it all before.

At open castings in Naples, Sorrentino auditioned more than 100 hopefuls for the role of Fabietto. What was he looking for? “I have no idea! I saw many, many actors. He was the best in terms of his ability. But the other element that made me choose him was that I did not understand him, and I still don’t. I don’t understand him in the same way I did not understand myself, the kid I was when I was 17. He’s a mysterious man. He could become a star. All the stars I have known are mysterious.”

Scotti had no comment on the likelihood of his imminent stardom, although he looked winningly sheepish as it was discussed. What he did say is that the night before his first audition with Sorrentino he was “super-nervous”, slept not a wink, and yet — mysteriously? — felt not at all tired when he arrived at the Palazzo Cavalcanti, on Naples’ via Toledo, for his chance to impress. He wasn’t a complete novice: he had acted on stage, in short films, and on a Netflix series, Luna Nera. But this was of a different order of magnitude. “It was shocking for me to see [Sorrentino],” he remembers of that first meeting. “It was like a cold shower. I just tried to focus on the lines as much as I could.”

He already had an inkling that he might be playing Sorrentino himself as a boy. “Sometimes,” Scotti said, “when you are going to an audition the first thing they say is shave your beard, take off your earring. Not this time. It was, ‘Keep your sideburns.’ A little detail. But I didn’t know for sure.”

Once he learnt the part was his, the fear intensified. In Venice, he turned to Sorrentino: “I don’t know if you remember that when we went to read the script together, I was like, ‘Paolo, are you sure? I mean you only chose me yesterday. There is still time to change your mind.’ I was pretty scared.”

Scotti maintained his equilibrium by shutting out too many thoughts of the heavy responsibility of reincarnating the director as a boy. “The thing about working with a great director is that everything around you seems simple,” he said. “Everything is so well organised. I remember that after the first meeting Paolo told me, ‘Read the script, memorise the scene, but don’t try to understand everything. We will jump together.’”

From the stage of the Dolby Theater in Los Angeles, in March 2014, Sorrentino dedicated his Oscar for The Great Beauty to his parents and his siblings, his collaborators, and his wife, as well as “Federico Fellini, Talking Heads, Martin Scorsese and Diego Armando Maradona.”

Anyone with even a passing interest in football — and plenty with none, such was his impact — will know that Maradona is considered by many to be the most gifted footballer ever. Sorrentino certainly thinks so. Near the beginning of The Hand of God, as rumours swirl about the possibility that Maradona might come to play for Napoli, an older character is asked how likely he thinks this is. “He’d never leave Barcelona for this shithole,” comes the world-weary reply.

But he did. In 1984 Maradona arrived to transform the fortunes of Napoli from hopeless also-rans to champions. Sorrentino speaks of Maradona, as Maradona did himself on at least one occasion, in religious terms. “What I know,” he told me, “is that Maradona is perceived by Neapolitans as a god. He was back then and he still is now. He appeared and disappeared like a divine entity, a spirit. He’s more important than San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples. He never landed and got off a plane in Naples, he just appeared. And then disappeared. And then in ’94 he was resurrected. And then he died in martyrdom. He was killed and he is now a martyr. Of course, people who are against him say he was a victim of himself — as we all are — but in his case I do think he was a martyr.”

The suggestion that Maradona, who died, aged 60, in November 2020, shortly after shooting wrapped on The Hand of God, might have squandered his opportunities as his life descended into chaos, is given short shrift by Sorrentino. “I don’t think we should judge harshly those who pass from being the poorest to being the most famous in the world,” Sorrentino said. “I know people who OD’d from much less fame.”

The scene in The Hand of God that might prove hardest for an English audience to swallow is the one that gives the film its title, when the whole of Naples, Schisas among them, erupts in celebration at Maradona’s impish handball against England, in the quarter-final of the 1986 World Cup. “A genius!” is the Neapolitan verdict on the Argentine’s revenge on the imperialist English, as the replays show that rather than magically outjumping the much taller England goalkeeper, Peter Shilton, Maradona has in fact punched the ball into the net. It is this act of outrageous, improvised cheek — we say cheating, they say whatever it takes — that seals the match in infamy, if you’re English, and Maradona’s reputation in infallibility, if you’re Neapolitan. (Or, presumably, Argentine.)

Visitors to Naples even today, almost 30 years after he left Napoli, will confirm that wandering the streets, one sees almost as many images of Maradona as of the Madonna — and she can be found on every other corner. Last year, following his death, Napoli’s famous old stadium, the San Paolo, was renamed the Diego Armando Maradona Stadium.

But Maradona has, perhaps, an extra special meaning for Sorrentino. “He was, for me, a symbol of something I hadn’t experienced,” Sorrentino said. “I come from a family who never brought me to see films, I never went to museums. I had very little relationship with art in general. My first taste of art was Maradona. He was an artist of football. He is the first one who made me see that an artist, in his expression, is able to transcend reality, which is what he did.”

Also, he saved a boy’s life.

Diego Maradona was born and raised dirt poor in the slums of Buenos Aires. His almost superhuman talent made him, for a time, rich and famous beyond dreams, or nightmares, a hero to millions, and then, as his life spiralled out of control, a villain to millions of others. A victim of his appetites, he was destroyed by drugs, bad company, terrible decisions. Sorrentino has made films before about men who fly too close to the sun, men who surrender to their worst instincts, causing harm to themselves and others. But The Hand of God is not about Maradona. It’s about an innocent teenage boy — not rich or famous or powerful or corrupt — who suffers a horrifying double-bereavement and finds escape in creativity, salvation in art.

“The truth is,” Sorrentino said, “I have never fully understood why I made these films about these older, powerful, corrupted men. I was just fascinated with them. And it was another way to escape reality, to distance myself and to go very far away, to find an alternative universe.”

Having completed The Hand of God, I wondered if he feels a sense of catharsis? “We’ll see,” Sorrentino said. “I made a film about Giulio Andreotti because I was obsessed with him. Once I’d made it, I was no longer interested in Andreotti. I hope it’s the same with my constant coming to terms with my biography. I don’t know yet.”

The film opens with an epigraph, a quote from the divine Diego himself: “I did what I could. I don’t think I did it so badly.”

Is Sorrentino able to say the same?

“Yes,” he said. “Yes. I think I am.”

The Hand of God is on Netflix from 15 December

You Might Also Like