‘Did I really need to risk my life?’: how the insane Cliffhanger left Sylvester Stallone to dangle

In the Dolomites – a vast mountain range in northern Italy – director Renny Harlin led Sylvester Stallone to the foot of an 11,000ft peak. Harlin pointed upwards. That’s where he planned to shoot Cliffhanger: at the top of the mountain. In the film – which dropped into cinemas 30 years ago – Sly would play a rescue ranger who battles a gang of hijackers. But the actor admitted to being scared of heights. Stallone – Rambo himself – swore he wouldn’t go any higher than the heels of his cowboy boots.

Cliffhanger was as much an expedition as a film production. The crew spent months in the Italian mountains (which doubled for the Colorado Rockies) with a team of world-class climbers performing stomach-lurching ascents. There were lightning storms at 13,000ft, helicopter evacuations, and – back in the US – a record-breaking aerial stunt. As expedition leader, Harlin had another job to add to those demands: coaxing Stallone higher and higher up the mountain.

Leaving the relative safety of those generously-heeled boots, Stallone did ultimately muck in by doing some climbing and dangling off ledges. A promotional making of feature was keen (a bit too keen, perhaps) to persuade viewers that Stallone had indeed done plenty of real climbing. But Stallone was nowhere near the Dolomites’ Vajolet Towers – a cluster of dizzying summits – for the film’s defining stunt: actress Michelle Joyner dangling on a line between the towers at 4,000ft. Indeed, any mention of Cliffhanger and Michelle Joyner’s big moment is almost certainly the scene that comes to mind – before it plunges gut-ward and triggers some primal, blood-freezing terror within. And it holds up. “When I watch it now, it’s really convincing that Stallone was up there,” says Joyner. “There’s no way you can tell that he wasn’t. I think, ‘So, did I really need to risk my life like that?’”

In the opening scenes, Sarah and Hal (played by Joyner and Michael Rooker) are stranded atop one of the summits and have to clamber across a zipline-like wire to the rescue chopper (a manoeuvre called a Tyrolean traverse). But the buckle on Sarah’s harness snaps and mountain rescue beefcake Gabe (Stallone) drops her. The purpose of the scene, of course, is to leave Gabe haunted by the guilt, which causes him to mope around like an emotionally-bruised lump of rock. But it also does for heights what Jaws did for sharks.

“People tell me that that scene is burned into their memory,” laughs co-producer Jim Zatolokin. “That’s the only thing they remember!”

Cliffhanger began in the mid-1980s, when co-producer Gene Hines saw a TV show about climbers. “That got him interested in the world of climbing,” says Zatolokin. “It’s a dynamic and unique world with a lot of characters.” They enlisted the help of top names. “We went about interviewing some of the great climbers and people from the climbing industry,” says Zatolokin. “We got stories and anything we could. We had five boxes filled with files of research.”

But there was a problem with chiselling the idea into a compelling film. “It’s an exciting sport, but not terribly exciting to watch,” says Zatolokin. “For a long time, it was difficult to figure out how to turn climbing into an action-adventure film. Die Hard was around at that time, and the concept became ‘Die Hard on the mountain.’”

Climber and writer John Long was brought in to put together a treatment. A member of the pioneering Stonemasters – a group of hippie-fied Californian climbers – Long did the first ever one-day ascent of the 3,000ft “Nose” of El Capitan in Yosemite. “He’s just legendary in the climbing world,” says Zatolokin.

Long’s premise was based loosely on his own novella – Rogue’s Babylon – itself inspired by the true story of the Yosemite dope plane, which, in 1976, crashed into a frozen lake carrying 6,000lb of Mexican marijuana. As word spread, it created a dope gold rush – climbers, hippies, and chancers descended on the wreck to scavenge the marijuana, which had been bundled into bales in burlap sacks. “I got there maybe two weeks after it was all over,” says Long. “At that time everybody was getting rid of everything. I had friends coming up with trash bags full of weed saying, ‘Here, you’d better take this!’”

Long considered his story “a piece of popcorn” and passed on writing the script. Instead, Michael France (who later co-wrote GoldenEye) penned the eventual screenplay. In the story, hijackers hold up a plane carrying $100 million of US Treasury money. But the plane crashes in the Rockies, scattering boxes of cash across the mountains. The villains – led by John Lithgow’s former intelligence mastermind – take the rescue team hostage, forcing the rangers to navigate the mountains and retrieve the $100 million.

“Die Hard on the mountain” is absolutely right. While Cliffhanger is arguably the last solid entry of the hyper-muscled, Sly and Arnie-led action era, it’s also a peak moment from a favourite ‘90s subgenre: the “Die in a [insert location]” action movie. We also had “Die on a battleship” (Under Siege), “Die Hard on a bus” (Speed), “Die Hard at a hockey game” (Sudden Death), and “Die Hard on Alcatraz” (The Rock). Harlin and Stallone were working on another variation called Gale Force – a criminally-unproduced “Die Hard in a hurricane” film – when they signed on for Cliffhanger. “Die Hard in a hurricane never happened because Harlin and Stallone jumped onto Die Hard on the mountain,” says Zatolokin.

Harlin was red-hot after the success of 1990’s Die Hard 2 (“Die Hard in an airport”), which was even more successful than the original. Stallone at the time, however, wasn’t so much climbing as clambering for a hit. A detour into light-hearted fare – mobster comedy Oscar and, erm, Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot – flopped. Stallone admitted that he’d “learned the hard way about comedy” and that Cliffhanger was his all-action comeback. “Cliffhanger is like a metaphor for my life – climbing and falling, peaks and valleys,” said Sly. “Do I have the strength to climb back up?”

If there was any doubt about the Die Hard-ness of Cliffhanger, see John Lithgow’s joyous turn as snarling, sadistic baddie Eric Qualen. Harlin later claimed that he wanted, rather bizarrely, David Bowie to play the villain (“We had a meeting and we talked seriously about doing it”) and then, more bizarrely, Roxy Music’s Bryan Ferry. Christopher Walken was cast but dropped out, which saw Lithgow promoted to lead baddie. Lithgow decided to go “the Alan Rickman route” with the character – classic English bastardry. Lithgow remains delighted at getting to fight Sly on an upside-down helicopter – while dangling off a mountaintop, naturally – and at all the skiing he did on his days off. Lithgow called Cliffhanger “the best job I ever had”.

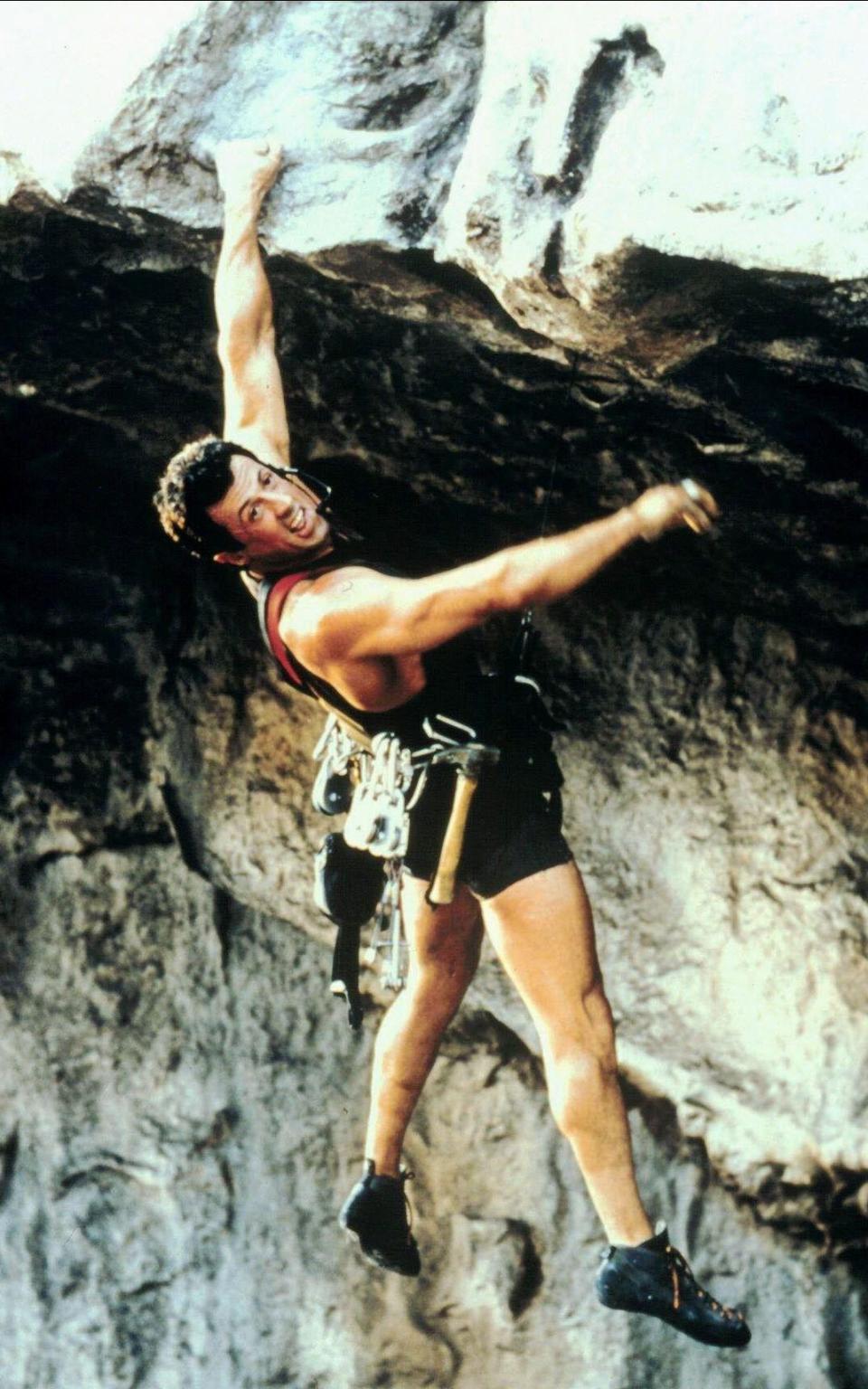

Bob Gaines, a veteran climber and co-author of How to Rock Climb books with John Long, joined the production as chief safety officer. His first job was to teach Stallone how to climb. Building a climbing wall in the grounds of Stallone’s Bel Air home, Gaines was impressed. “He climbed a 5.10c – that’s sort of expert level,” says Gaines. “That shows he had tremendous athletic ability, and his level of fitness was extremely high. Climbing a 5.10c on your first day is one in a thousand.”

Though Gaines planned to take Stallone for some big climbs on actual rock faces, Sly didn’t want to venture into the great outdoors – perhaps due to his fear of heights. Michael Rooker, however, became a keen and capable climber. “He did some big climbs in Joshua Tree – 500ft,” says Gaines. But he couldn’t fault Stallone’s commitment to the action in the mountains. “On location he was no prima donna,” says Gaines. “I was amazed at what he would do. He’d jump off a snow slope and do somersaults, no problem.”

Ron Kauk and Wolfgang Güllich – considered the best climbers in the world at that time – were enlisted as climbing doubles. Kauk, speaking in 2021, described how he was too slender to double Stallone, so Stallone’s trainer suggested that Kauk start using steroids to bulk up. He was relieved when Güllich – closer to Sly’s physique – did most of the doubling for Sly. Güllich also wore prosthetics to look even more like Stallone. According to Gaines, Sly had wanted Güllich to be his double after he saw the German climber performing one-finger pull-ups. Cliffhanger would be dedicated to Güllich’s memory. He died in a car crash in August 1992.

Production was based around the town of Cortina d’Ampezzo, with the cast and crew transported between basecamp and mountain locations via helicopter. For Michelle Joyner, there was no being coaxed up the mountain. It was a caveat of being cast: she’d have to go up there. Renny Harlin explained at the audition that he wanted to start the film with a continuous helicopter POV shot that finds her and Rooker stranded on the mountain. “Renny said, ‘There’s no place for the helicopter to land, so you’ll have to be dangled out of a helicopter on a line, and someone will be there to grab you, pull you down, and anchor you to the mountain with a harness,” recalls Joyner. “That was the first thing we did. It wasn’t fun!”

Shots of Sly up on the Vajolet Towers summit – and dangling on that fateful line – were filmed in the studio. Shots were then intercut with footage of Joyner, Rooker, and Sly’s stunt double, Mark De Alessandro, up there for real. As far as Joyner recalls, Stallone “never got more than a few feet off the ground” for their scenes. Joyner soon acclimatised to the height by zipping back and forth across the line at 4,000ft, and running across an Indiana Jones-style rope bridge. “By the time we actually shot my stuff, I wasn’t scared anymore,” she says.

Joyner wore two harnesses for the scenes. One harness was part of her costume and was rigged to break on cue. The other was a real harness with a wire that ran under her arm and kept her dangling safely. When the rigged harness broke and Joyner had to let go of the above line, suddenly hanging by the hidden wire only, the fear kicked in. “When I got off the wire that day, I couldn’t even walk,” she says. “My legs just went out from under me. In retrospect, I probably shouldn’t have done that stunt! Not that I thought it would go wrong, it was just super scary. I was in tears. Even when you’re pretending, your body doesn’t know that. You still shake and your legs get weak. It’s just a natural human response.”

When Joyner arrived to film her studio-based scenes, she received a standing ovation for her gutsy stunt work. But her relationship with Stallone was – much like those mountaintops – frosty. She wonders if it was because of the ovation she received. “I don’t think he appreciated that,” she says. “I was like a reminder that he didn’t have the same balls that I did to be up there.”

What’s so terrifying about the scene is the terror itself – Sarah’s realisation that death, and a horrible one at that, is coming her way fast. The scene was also loosely inspired by a real-life incident. In August 1986, a climbing novice fell to his death during a session in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, after failing to loop a rope into his harness properly. The instructor in the incident was climbing legend and Stonemasters mentor, Jim “The Bird” Bridwell. One climber, posting about it on a forum, described how Bridwell opened up around a campfire years later – he described the horror in the man’s eyes as he fell, knowing he was about to die.

The fall in movie – dubbed “Sarah’s death drop” – was created by splicing together shots of Michelle Joyner hanging at 4,000ft and later dropping onto an airbag in the studio, along with footage of a dummy and the stunt woman, Georgia Phipps, plummeting 400ft on a descender cable. “I drew the line at that,” says Joyner. “But we were all up there cheering and watching.” David Breashears, a mountaineer and filmmaker, worked as a camera operator and detailed the experience in a memoir, High Exposure. Breashears had been concerned by the drop. Instead of using climbing ropes, which stretch, the stunt team used a cable. If it reeled out incorrectly, the cable would have snapped.

For Bob Gaines, weather was a bigger concern. Production had been immediately delayed for two weeks – “I think it was the biggest claim ever for weather insurance in the history of motion pictures!” says Gaines – and when production began proper, mists and lightning would suddenly move in, forcing the crew to evacuate by helicopter. Sometimes they couldn’t evacuate fast enough and they’d have to sit it out. Breashears described being surrounded by steel towers, which had been erected to hold cameras. “We were standing on the perfect lightning rod, and huge bolts of electricity crashed to the ground all around us,” he wrote. “As each strike exploded like a bombshell, crew members would run in every direction.”

“Five people were hit by ground current from the lightning,” says Gaines. “One guy got jolted off the cliff and went over the side. He landed on a ledge 15ft below.”

British actor Craig Fairbrass, who plays the main henchman, also recalls being pinned to the mountains by storms. “I’m not great with heights,” he says. “Some of the places we were shooting were genuinely terrifying. I remember being up high – very high – and we were latched in with clips. You’d change the ropes and clips as you walked round the edges. I could never look down. I’d have just froze. Every now and again you’d hear this giant rumble from an avalanche.”

For Fairbrass, it was a case of right time, right place, right build, right accent. “I was a 6’3” cockney,” says Fairbrass. His character – a footballer-turned-hardened criminal – calls Michael Rooker’s character “a loudmouth punk-slag” and then boots him around like he’s taking a penalty kick. (Though he calls football “soccer”, a word that no self-respecting Englishman would use. “I still get messages from people saying, ‘I can’t believe you called it soccer!’” laughs Fairbrass. “I say, ‘I didn’t write it! Stallone changed it!”)

An obvious riff on the second-tier villains from Die Hard, Fairbrass’s henchman personifies the pleasure of Cliffhanger: formulaic, sweary, with plenty of muscle, and deliciously violent. Cliffhanger also one-ups Die Hard with its satisfying henchmen deaths. Fairbrass’s character gets blasted with a shotgun and thrown off the mountain – a satisfying comeuppance – while Leon Robinson’s baddie is skewered on a stalactite, an exquisite action movie death.

For the final stunt, British stuntman Simon Crane made an aerial transfer between two jets at 15,000ft. The stunt cost $1 million and was named by the Guinness Book of Records as the most expensive aerial stunt ever. It had been scrapped at one point but Stallone paid for it himself. “It probably came out of his per diems,” jokes Crane.

Though well-rehearsed, the jet transfer – performed while doing 150mph – went less than smoothly. “It was extremely cold at that altitude and speed – minus 40 or 50,” says Crane. “I had to be covered with a prosthetic mask. I was also wearing a gas mask and an SAS survival suit, with a hidden parachute. But my hands were covered so it was difficult to get to the release in an emergency. A hidden parachute is always dangerous because it has to open through your costume.”

Crane, doubling as one of the hijackers, was winched out of the first jet and pretended to slide down a weighted line. “The idea was that the other jet comes in behind in formation, the door opens, and they grab the weight and pull me in. But they missed the weight. It went over the wing of the plane and underneath the engine.” He continues: “I missed the door, hit the side of the plane, and bounced onto the roof. Luckily, I just missed the engines… The pilot heard me battering down the top of the plane and banked violently to one side, which threw me to the other side. There was nothing to hold onto.”

Crane managed to parachute to safety. He offered to do it again but he was denied. “The outtake looks scarier than the real thing,” he says.

Cliffhanger opened in cinemas on May 28 1993. Critics weren’t hugely impressed with the formula. The Daily Telegraph’s critic called Cliffhanger “high-energy, high-altitude tosh”. But it made a mountain of cash – $240 million worldwide – and outgrossed Die Hard 2. It also bagged three Oscar nominations.

There was some off-screen drama, with reports of financial difficulties at production company Carolco Pictures (eventually sunk by Renny Harlin’s 1995 pirate disaster, Cutthroat Island), and wrangling over the writing credits. Cliffhanger also raised a few eyebrows in the climbing community for some less-than-grounded scenes: Sly using a bolt gun to fasten safety equipment into a rockface (“There’s no such thing,” says Long. “How would you shoot anything into fine-grained granite? A bullet can’t even go into it!) and Joyner’s broken buckle (“That doesn’t happen,” adds Long. “Stuff doesn’t break.”)

The climbing gear brand that supplied the harness, Black Diamond, was apparently unamused. The credits would include a disclaimer to say the harness was “altered to create the accident depicted”. “I think putting it in the credits made it worse,” laughs Bob Gaines, who recalls how his climbing students balked at using the harness post-Cliffhanger. “People were going, ‘That was a Black Diamond harness that failed!’”

Stallone has now signed on for a belated sequel. But will a CGI era action film brave the literal heights of Cliffhanger? It remains one of most impressive action films ever produced, made on a scale that goes way beyond your average Die Hard knockoff.

And, like poor doomed Sarah hanging from that line, it makes the stomach lurch 30 years on. “It’s still hard for me to watch,” says Michelle Joyner. “I was actually up there.”