Dali/Duchamp, Royal Academy, review: A sometimes silly, sometimes lovely juxtaposition of the artists' work

The idea seems improbable. Was there really much in common between that consummate, wax-moustachioed showman Salvador Dali and the cerebral, secretive Marcel Duchamp, founding father of conceptual art, and inventor of the idea of the ready-made? No exhibition-maker has ever tried to prove a serious connection – until now. And it is convincing, at least in part.

The show is very well done. It teems with objects of fascination - photographs, paintings, sculptures, documentation by the vitrine-full. It's far too crammed into the spaces allotted to it. You could say it deserves better than this, more elbow room. But when an institution is also hosting major shows about Matisse and Jasper Johns simultaneously, what is there to be done? Things will be a little easier next year, when the Royal Academy finally expands into the space once occupied by the old Museum of Mankind on its 250th birthday.

So what did these two have in common? They were friends for decades – photographs prove it. They collaborated on an entire room at the exhibition of International Surrealism that was staged in Paris in 1938. That room is partially re-created here. It's a dimly lit, grotto-like space with clusterings of old coal-sacks hanging from the ceiling, and sexy mannequins adorning the walls (only grainy photographs of these; the pendant coal-sacks are real enough.) Above all, they were both profoundly impish, ready to take the Michael at every possible opportunity, re-thinking what painting or sculpture or the very idea of the art object might become in the 20th century, decades after photography had begun to rob it of its reason for being: the depiction of the reality we see in front of our noses.

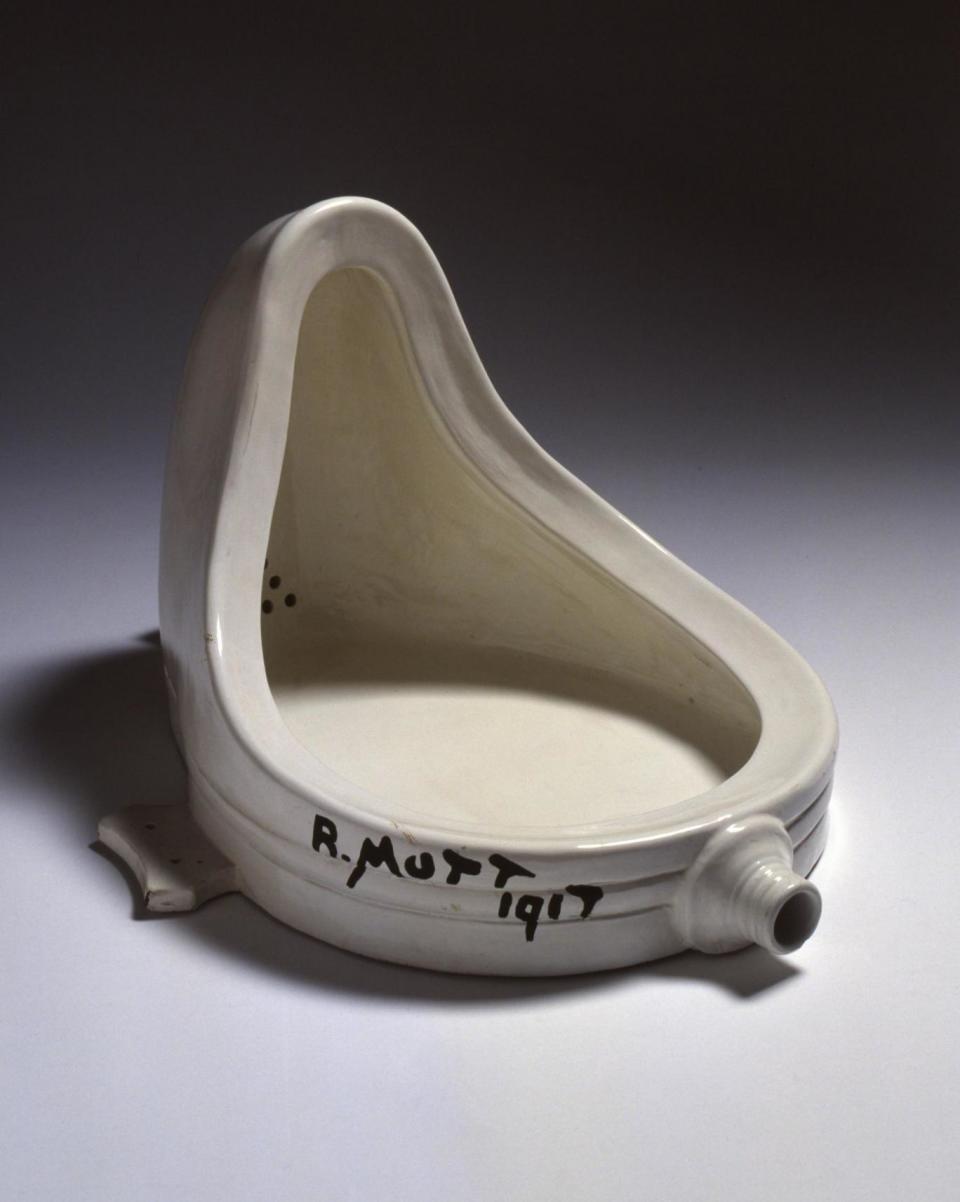

So we have an entire cabinet of three-dimensional objects made by both of them. Duchamp's (or R. Mutt's, as he chooses to call himself) urinal sits cheekily, and perfectly at ease, beside Dali's lobster telephone. Well, not quite perfectly at ease perhaps. A lobster telephone is not exactly a ready-made, is it, because Dali's whole idea was to point out the sheer incongruity of putting the two together? Other ways of proving that they had things in common are rather silly. In the first gallery, Dali's very best painting, a portrait of his father of 1925, hangs close to Duchamp's portrait of his father. They are quite different stylistically. So they both did paintings of their fathers? What does that prove?

Much is proved to our satisfaction in this show though. The whole thing is a lovely, glancing, pirouetting dance through the converging interests - from eroticism to the game of chess - of two formidably amusing and clever tricksters – when at their best that is; when the leering, mock-menacing, narcissistic Dali is not being a complete pain in the neck.