Could Alan Ayckbourn’s most notorious play have been written today?

On stage, a depressive married woman is wandering her kitchen looking for ways in which to kill herself. She variously tries to jump from the window ledge, charge into a bread knife, overdose on sleeping pills, gas herself in the oven and hang herself from a light socket. At each point, she’s thwarted by people bustling in and carrying her away from her single-minded task with heedless good cheer and accidental concern. “That oven can wait. You clean it later,” she’s told, chivvied out of her prone position. A glass of wine is later produced, the split second she’s poised to glug a bottle of paint stripper. And so on.

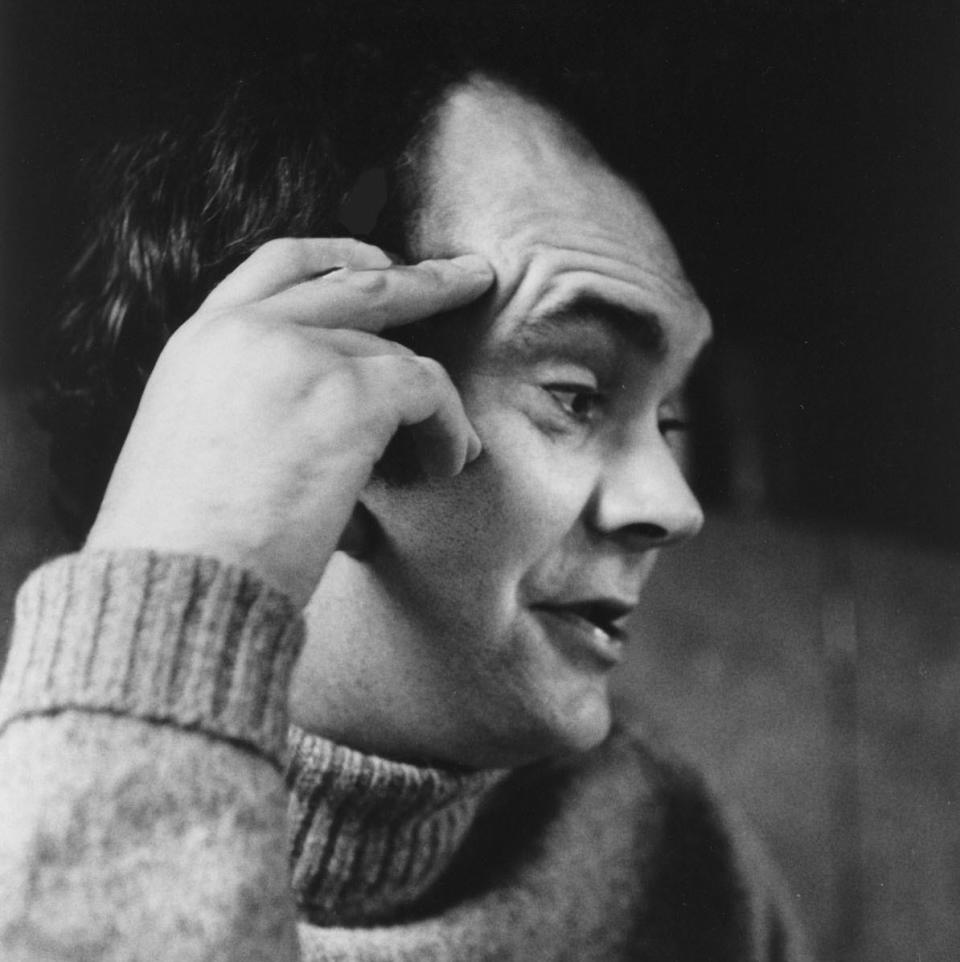

The stuff of sober, serious drama? No, actually, the wildest laughter. The second act of Alan Ayckbourn’s Absurd Person Singular – 50 years old on Sunday – ranks as one of the most startling sequences of black comedy ever seen on stage. Eva Jackson, worn down by her marriage to the philandering architect Geoffrey, says nothing during the scene, she is so intent on the mission at hand. But the roars filling the auditorium when the play is underway can be borderline deafening.

At least, that’s how Sheila Hancock remembers the London premiere run in 1973. Hancock played Marion, the grandest of three wives in Ayckbourn’s bleak midwinter comedy. The play entails three successive Christmas gatherings attended by three couples – each from a different place in the social pecking order, denoted by the men’s professions (tradesman, architect, bank manager). The action takes place in their respective kitchens rather than the living room.

“It produced some of the biggest laughs I’ve ever heard in the theatre,” Hancock reflects, incredulous. “Here’s a girl trying to take her own life, and yet it is somehow hysterically funny. There used to be rounds of applause during that suicide scene, which was extraordinary.”

“It was dangerous laughter,” is how Anna Calder-Marshall puts it. She was Eva in the first West End run, opposite her real-life husband David Burke as Geoffrey. It might sound like a shocking reaction from another age. Except Absurd Person Singular has stayed in the repertoire and still makes people laugh.

Or it does for now. You don’t need to be constantly on the lookout for offence-takers to wonder whether, in an era when a premium is placed on avoiding upset, and outcries can virally escalate, a work such as this might fall foul of the Twitter mob, or find itself out of favour among theatre bosses who are so often in thrall to the latest liberal pieties.

The irony being, of course, that beneath the play’s mirth are serious points about bullying husbands and the strain women are often under within a marriage. “Ayckbourn is a great master of domestic violence,” says Maureen Lipman, who played the neurotic housewife Jane Hopcroft to triumphantly twitchy effect in the BBC’s lavishly cast 1985 adaptation. “He’s more believable than Pinter, because it’s based much more clearly on real home life.”

There were no angsty discussions among the cast when they recorded their version, says Lipman. “We didn’t have ‘woke’ in the dark ages,” she adds. “It was before being triggered came in. I worry that a lot of wonderful drama won’t be allowed. If you stop the comedy, the serious point won’t get made.”

That the play was written from a feminist standpoint is confirmed by the author himself. “I have the Jane Austen point of view. I write from the kitchen,” he explains from his Scarborough home. Growing up around women (his mother Lolly was the main parental figure in his life, his violinist father not being around much in his childhood), he saw that “they weren’t having a very good deal. And when I was young I was shocked by the inequality of things”. Some critics see the play as anticipating Thatcherism in showing the get-ahead, self-interested Hopcrofts rise, but it’s also possible to view it, in Eva’s new self-composure in the third act, as a harbinger of female empowerment.

Ayckbourn acknowledges that the climate has changed. “There’s a lot of nervousness now about bringing comedy to areas traditionally dealt with seriously. There’s an awful lot of, ‘You can’t say that’ in comedy terms. You read about comedians running into brick walls. It’s a delicate steering act these days.”

Not that he was ever blasé about the subject matter. It was nail-biting waiting for the opening-night response (at the Library theatre, in Scarborough). “I had that nightmare: what if the entire first-night audience had relatives who had made recent suicide attempts? I was anxious but also confident,” he admits.

“The laughter is aimed at those helping Eva. The actress [in 1972, the late Jennifer Piercey] must play it straight otherwise you are saying ‘Aren’t people trying to kill themselves funny?’, and that is a disaster.”

Christopher Godwin, who played the bank manager Ronald in the original 1972 run, recalls the sheer relief when it became clear the audience was on-side, and alert. “You weren’t sure how they were going to take it,” he says. “You got this odd sense of them finding out what they were laughing at.”

The play transformed Ayckbourn’s reputation. His two early big successes, Relatively Speaking (1965) and How the Other Half Loves (1969), evinced a gift for genial social comedy. Absurd Person Singular blasted assumptions about his being a mere boulevardier. In the West End it became his greatest long-runner, and went to Broadway too, where it was the longest-running British import since Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit (1941).

It has been performed worldwide, and translated into more than a dozen languages. And you can perceive its influence, I’d suggest, in work as lauded as the Noughties BBC sitcom Nighty Night, Julia Davis’s wickedly funny evocation of a heartless beauty parlour owner exploiting her husband’s terminal cancer, or After Life, in which Ricky Gervais’s hangdog hero battles grief after his wife’s death, the humour bubbling from the worst circumstances. Interestingly, the first script written for Reece Shearsmith and Steve Pemberton’s comedy series Inside No.9 was the Nana’s Party episode – knowingly modelled itself on Ayckbourn.

The characters were based on real people. “I knew several blokes like Geoffrey and several manically depressed actresses,” says Ayckbourn, 83. He acknowledges that his now-wife Heather Stoney influenced the spick-and-span Jane (“If she sees a spillage she will mop it up immediately”). His agent, the legendary Peggy Ramsay, informed the airs and graces of Marion. “She swept through my house like a whirlwind, throwing open doors, and saying, ‘Oh, what lovely cupboards!’. She was making all the right noises but she wasn’t interested in any of that.”

As a document, the play points up how much things have changed. Just in terms of social convention, it takes us back to a more uptight time. “You had to make a great effort, didn’t you? If someone asked you round then you had to ask them back – ‘Oh no we’re on a treadmill’.”

“It’s interesting to have lived through so much as a writer and see not just the rise of women but the decline of men,” he adds. “The alpha male is a dying species.”

We learn a lot from the play, and from Ayckbourn’s oeuvre as a whole. But it’s as if we need to be kept reminded of its value, and his importance. French filmmaker Alain Resnais adored Ayckbourn, and you can detect philosophical profundity in his tightly theatrical formulations about the human condition, the way imposed societal order unravels us.

Tracy-Ann Oberman, who played Eva in a regional revival in 2011, possibly speaks for many in admitting she went into the production not being Ayckbourn’s biggest fan, but says she, “came out of the first rehearsal realising that he is our Chekhov. He understands the absurdity and tragedy of existence so well.

“The sexual politics are clever,” she adds. “In the 1970s the audience may have laughed at Eva, but my sense was they understand where the [suicidal] impetus comes from. My uncle used to say that even in Auschwitz there were laughs – there’s a hair’s breadth between laughter and tears. The release in the audience every time an attempt went wrong was palpable.”

Busy writing as ever, Ayckbourn is looking to the future but points out the value of presenting work from a bygone era. “The only way we can move on is by looking back to the past and being honest about it,” he notes. Only by saying, ‘this is who we were’ can we begin to work out who we will be.”

There will be a 50th anniversary reading of ‘Absurd Person Singular’ on Sunday at the Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough. Alan Ayckbourn’s new play, ‘Family Album’, runs from Sept 2 to Oct 1. Details: 01723 37054; sjt.uk.com