Christine Keeler's son: 'My mother was raped at knifepoint – so why was she the one who went to prison?'

Without doubt, the most famous picture of Christine Keeler is the cheeky portrait taken in 1963, at the height of the Profumo affair. It shows her astride a plywood chair at comedian Peter Cook’s Establishment club in Soho, apparently naked and looking boldly at the camera. Another picture of Keeler, framed as a reminder of her young self – and now owned by the younger of her two living sons, Seymour Platt – could not be more different. She’s lying in a field of flowers on a sunny afternoon, windswept and apparently carefree.

That black-and-white photograph moved home with her many times, last hanging on the wall of a modest flat in Beckenham, Kent, where Keeler spent her final years. ‘It was part of a limited edition which was signed by her and she had carefully covered her signature with masking tape so you could not see it,’ says Platt. ‘I thought this was really telling about who she was – and who she did not want to be.’

The picture was taken the day Keeler was released from prison in 1964, having served six months of a nine-month sentence for perjury. She was still only 22 but her name was already a byword for scandal.

As an aspiring model, Keeler had hit the London party scene at the beginning of the Swinging Sixties, under the wing of Stephen Ward, an osteopath whose clientele included famous names in the aristocracy, politics and show business. Ward’s entrée into high society relied on a coterie of pretty girls who would entertain his important friends.

Through Ward, Keeler met John Profumo, the government’s (married) Secretary of State for War, and Eugene Ivanov, a naval attaché at the Soviet embassy in London. The discovery of her – simultaneous – affairs with both men saw her cast as a femme fatale.

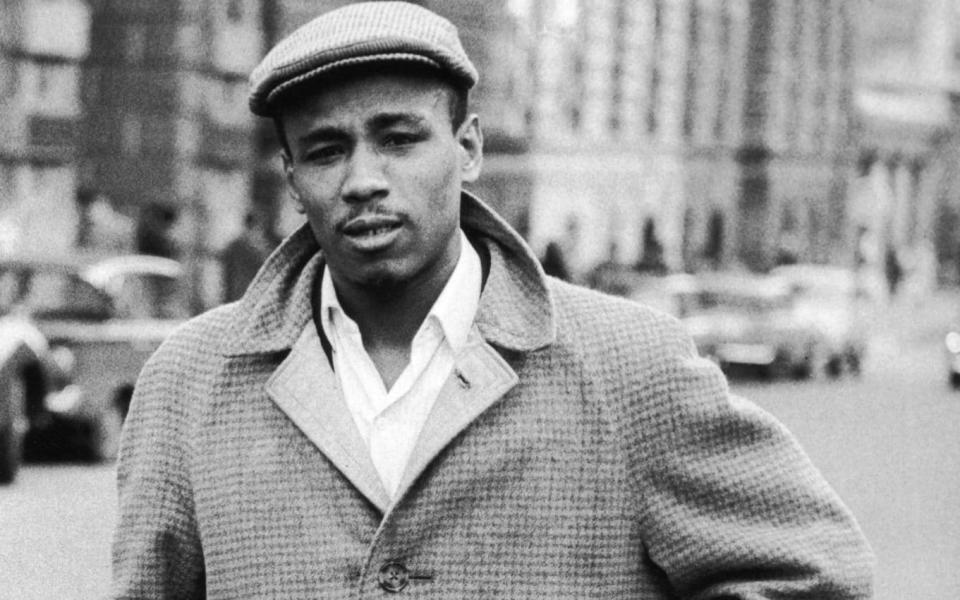

In reality, according to her son, Keeler was a victim. He says that she was not only being used by powerful men but, at the same time, she was being stalked by Lucky Gordon, a jazz musician, who became obsessed with her, and raped and violently assaulted her. When she complained to Ward and to the police, Platt says no one took her seriously.

Gordon was eventually prosecuted for actual bodily harm but in her statement Keeler hid information about two witnesses to the attack and was later caught out. Gordon was released and she was convicted of perjury.

The conviction cemented her place as one of history’s bad girls, but is it time for a reappraisal? Keeler’s son and a growing number of supporters believe it is. ‘My mum knew she was hated in the country, she had seen her reputation destroyed in the press and even in Parliament,’ says Platt.

‘She must have pleaded guilty to perjury because she knew she could not get a fair trial.’

The pardon process

He intends to appeal for a pardon and has appointed Felicity Gerry QC, an internationally renowned advocate for women’s rights, to lead the posthumous application. It will be submitted to the Lord Chancellor this month.

‘Not every lie is perjury,’ argues Platt. ‘There can be coercion, fear, or trying to hold on to some shred of dignity. There are lots of reasons victims of violence don’t tell the truth.’

Having grown up amid his mother’s notoriety, as an adult Platt, 49, has kept firmly out of the spotlight. A business analyst, he lives quietly in Co Longford, Ireland, with his wife, Lorraine, and daughter Daisy, 12.

He is emerging now because of a last request Keeler – who died in 2017 – made in her will. She asked her son to tell the truth about her life and the events of the 1960s.

At first he was uncertain, but as the Me Too movement gained traction, he began to understand how even apparently successful, desirable and famous women could be abused by men, then belittled or disbelieved when they tried to speak up.

‘I’d love there to have been a happy ending for her but her life was always tough,’ says Platt. ‘I wasn’t able to protect her from what went before but it makes me proud to think I can do the right thing for her now.’

Meeting Lucky Gordon

When Keeler met Gordon in 1961, she was a carefree girl about town. She was three months into her affair with Profumo, whom she had met that summer at Cliveden, Lord Astor’s beautiful Berkshire country house.

By the time she stood in the dock charged with perjury, two years later, Platt says Keeler was ‘broken’ – in part by the scandal over Profumo, but mostly because she had been stalked by Gordon and had no one to protect her.

The pair first got talking at the El Rio Café in the then-run-down Notting Hill neighbourhood. Gordon asked Keeler on a date. He telephoned repeatedly and eventually she agreed to meet him for coffee. He told her he had some stolen jewellery he wanted to show her at his flat. When they got there, he pulled out a knife and told her to strip, then raped her, her son says, holding the blade to her throat.

He released her 24 hours later, after she persuaded him that Ward would know she was missing and after promising to return. When she recounted this to Ward, Platt says that Ward told her what an idiot she had been to go to Gordon’s flat at all. The crime was not reported to the police.

Platt says that Gordon became obsessed with his mother. ‘She lived in fear of what he might do. She did not know whether it was best to reject him or be nice to him and try to persuade him to leave her alone.’

The following year, he attacked Keeler again, this time after barging into Ward’s house, where she was staying. Furious at the intrusion, Ward called the police. ‘The police turn up and lecture Christine on how stupid she’s been and tell her not to put herself in a position like that,’ says Platt. ‘This is typical of the treatment women get – even today – if they have been earmarked a certain way.’

Several other violent incidents followed. As she headed out to a nightclub one evening in April 1963 with friends, Gordon was lurking outside. He accosted her, an argument broke out and Gordon hit her so hard she fell on the pavement. As she scrambled back into her flat he followed, continuing to hit her.

The police were called but according to Platt, the two men present, friends of her flatmate who Keeler had just met, begged her not to say they had been there, not wanting to get caught up with the police.

In her police statement Keeler said that there had been no witnesses. When it later emerged to be otherwise, Keeler was charged with perjury and attempting to pervert the course of justice.

She pleaded guilty to the former – Platt suggests that she was likely advised to do so in hope of a more lenient sentence – but crucially, she never withdrew her allegation of assault. Yet Gordon, who had been sentenced to three years, was released after just one month. Keeler served six months for perjury. ‘How can that be fair?’ asks Platt.

Why Keeler really pleaded guilty

Keeler’s barrister, the late Jeremy Hutchinson QC, once described Keeler’s voice as holding ‘no emotion, tired and defeated’ at the perjury trial. Platt argues that his mother was depressed and traumatised during the hearing, her friend Ward having recently died by suicide and also because she was being followed by paparazzi. ‘No wonder she decided to plead guilty and get it over with.’

Some years later Keeler told him that being sent to Holloway prison was a relief: ‘It was an escape,’ he tells me. ‘After the year she’d had, at least it was a place to get away to and where she’d be safe.’

As part of the application for pardon, he had to write a victim impact statement. ‘I had to think long and hard about how all this affected her. I feel more and more strongly that the system let her down.’

So, could the same thing happen today? James Harbridge, a solicitor who has been advising Platt, says we have come a long way since then: ‘I don’t think the situation would have escalated as it did. There was a pattern of behaviour. The police were called [to incidents involving Gordon threatening or assaulting Keeler] five times. You can now report stalker activity. I don’t think that concept existed at the time.’

‘There was a public appetite for wanting to punish Christine and a need for the establishment to put her in her place,’ adds Platt.

‘One of the saddest aspects of it all is that she agreed: she accepted the idea that she deserved to go to prison because she’d been told so often that she was bad… She was very scarred by everything that happened to her in 1963 and she carried that through her life.’

Becoming Christine Sloane

Keeler grew up in Wraysbury, near Heathrow airport. In her memoir, published in 2002, she wrote that her stepfather sexually abused her when she was 12 and asked her to run away with him. ‘She told me that when she was in the bath he used to insist on coming in and washing her chest,’ says Platt. ‘She used to sleep with a knife under her pillow. When I was growing up she didn’t have many boyfriends. She always told me, “I don’t have men in my life, Seymour, because I don’t want anyone f—ing you up.” She really did believe men had the capability to screw kids up.’

At 16, Keeler gave birth to a baby, Peter, who died after six days. A few months later she moved to London and worked as a waitress before becoming a dancer at Murray’s nightclub and landing some modelling jobs.

Artist Caroline Coon got to know her and said later: ‘Christine was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen, she took your breath away. Every man who met her wanted her and those who couldn’t have her wanted to punish her.’

Soon after she left prison Keeler married James Levermore and in 1966 they had a son, James. The boy was raised by Keeler’s mother, and mother and son were estranged. ‘Chris never bonded with Jim, she never had that chance,’ says Platt today. ‘I think that was her greatest regret, that she never had that relationship with her other son.’

Seymour was born five years later. His father, businessman Anthony Platt, left soon after he was born and he saw little of him while growing up. Platt says he hasn’t seen his half brother James for more than three decades.

By then, his mother no longer considered herself ‘Christine Keeler’ but ‘Christine Sloane’, a name selected at random when she was standing in Chelsea’s Sloane Square. She would refer to ‘Christine Keeler’ as if she were a third person. ‘She’d be very dismissive of Christine Keeler,’ says Platt. ‘“Who could like her?” she’d say. “She was wrong, she was immoral.”’

Platt remembers his mother – who he had called ‘Christine’ since he was a teenager – as a complicated woman, sometimes very funny, a fast driver and a terrible cook. Hard as she tried, she could never get on her feet. Having a criminal record meant she struggled to find a ‘regular’ job and in any case, she was a social pariah. ‘She said if she got a job in a shop people would just come in off the street and shout at her.

‘She found relationships difficult,’ he recalls. ‘She wasn’t well all the time and she would have periods of depression, though I knew I was loved. She told me the moment I was born, when she looked into my eyes, she fell in love with me. And that’s a nice thing. If you have the devotion of a parent it really does give you a firm footing.’

They scraped by on benefits, with Keeler earning money where she could, by giving interviews or, briefly, trading off her rackety past by writing an advice column for a pornographic magazine. ‘She was proud, so she never took all the benefits she was entitled to. For a long time in the 1970s we lived on child benefit, which was £11 a week.’

He remembers feeling hurt when another child’s father stopped them playing together, saying he did not want ‘that mother’s son’ near his child, but most of the time he accepted life as it was. ‘To me, it was normal that every so often you’d have a journalist come round wanting to talk to your mum.

‘At the height of the Yorkshire Ripper murders, two policemen turned up at our house and I overheard her telling a friend they’d come to warn her that there was a serial killer attacking prostitutes in Yorkshire and because she was such a famous prostitute she might want to be careful. She was furious. She was never a prostitute, but in the eyes of the world that’s what she was.’

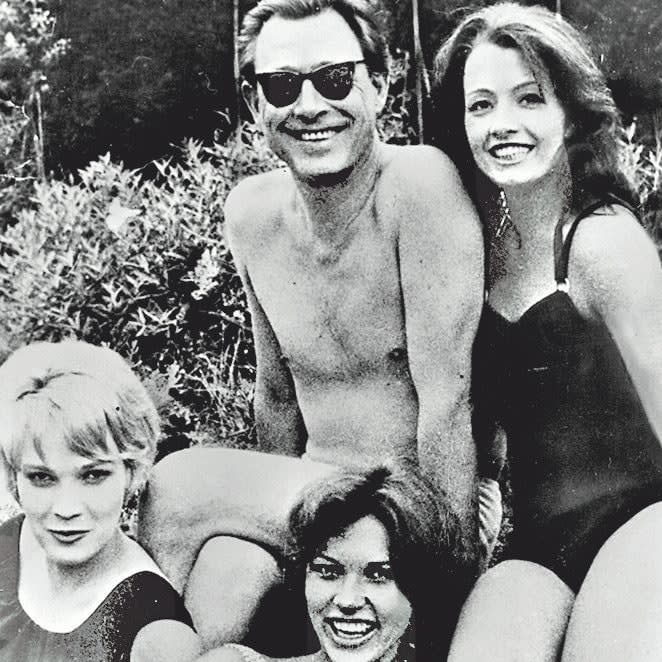

It was only in 1989, when the film Scandal, based on Keeler’s book of that name, was released that Platt realised the magnitude of his mother’s fame. The film starred Joanne Whalley as his mother and John Hurt as Stephen Ward. ‘She hated it,’ says Platt. ‘But that was in her nature. I don’t think she had any appreciation for dramatic licence.’

The premiere was a Who’s Who of 1980s stars. ‘Bob Geldof was sitting next to my mum with Paula Yates. I tripped on some stairs and when I looked up, Phil Collins was standing there. It hit me that this was special.’

However, the scandal was also something Keeler never fully moved past. ‘She was always expecting to be betrayed, which was hard,’ says Platt. ‘Paranoia is a funny thing… It was very difficult to talk to her about her life. She’d get suspicious, even of me. She’d say, “Why are you asking, do you want to write a book?” I don’t have many pictures of Chris, maybe a handful from my wedding. She didn’t want her picture taken in case it ended up in the papers.’

Christine's difficult later years

When his daughter Daisy was born, Keeler cut off contact. ‘There was this little girl coming into the world and she wanted to protect her from her legacy,’ Platt says. ‘We had a very difficult few years when she was pushing us away for [Daisy’s] own good. That was the human price paid for all this.

‘It was only when she got sick that she got in touch again. So Daisy didn’t see her grandmother for the first few years of her life, though later they got to know each other and they’d speak on the phone.’

By that time, aged 73. Keeler was battling lung disease. When she gave him a copy of her will, Platt put it into a box, where it was joined by a sheaf of press cuttings and his mother’s rosary beads after she died, aged 75.

After probate was granted the will was published – with its line asking him to tell the truth about her. ‘I got a call from a journalist, saying, “Well, what’s this truth you’ve got, then?” And I said, “I don’t know.”’ Eventually it dawned on him that she wanted him to tell the world how badly she had been treated.

That feeling was reaffirmed last year when he watched the BBC drama The Trial of Christine Keeler. ‘One of the producers said to me, “It was terrible, what the police did to your mum,” and I thought, “It’s not just me, then, something really did go wrong here.”’

Platt began creating a timeline of events relating to court hearings in which she was involved, as a platform from which to launch a campaign for a pardon. Today it is meticulously documented on a website (see below).

‘She is thought of as the good-time party girl but it’s shocking to see what she went through,’ he says. ‘I feel sad at her missing out on our family life and angry that she hasn’t had justice.’

A pardon would be a form of redress for the hurt Keeler carried with her. ‘I do feel I’m doing the right thing,’ reflects Platt. ‘I need to fix this for my mum and I need to fix it for history because people still don’t understand the story, they still blame the women and call them liars and that’s wrong.’

It would also be a source of satisfaction for her son, the one man in Keeler’s life whose devotion to her never wavered.

For more information about the pardon application, visit christine-keeler.co.uk