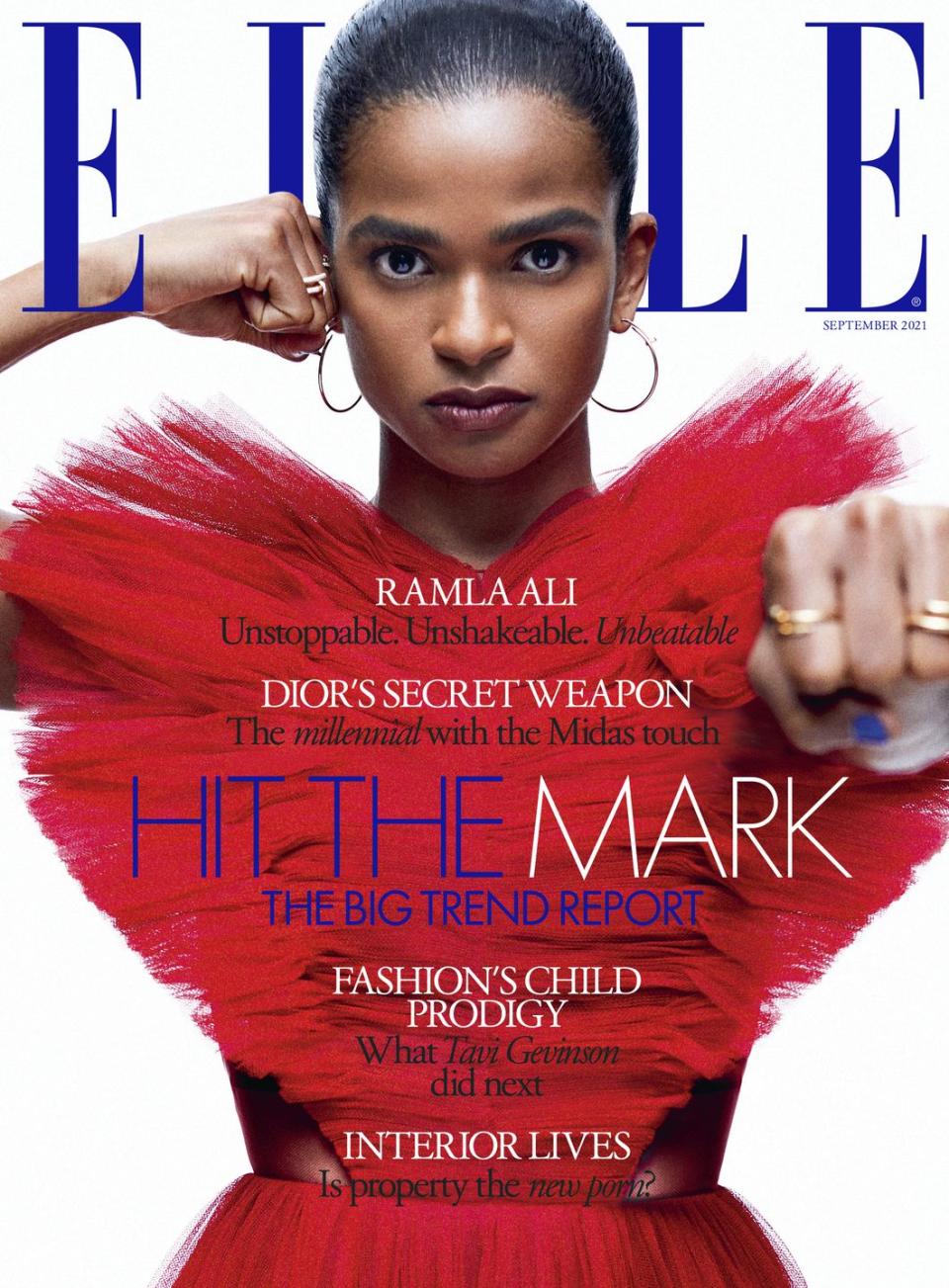

Champion Boxer Ramla Ali On Ambition, Activism And Antony Joshua

Ramla Ali is deflated. We’re sitting inside a boxing ring in the west London gym where she trains. We’re in the ring because the rest of the – all-male – athletes are training, loudly. At least here we can hear each other talk. The scent of stale sweat and a whiff of urine (she says the toilets were recently broken) linger in the air. Discarded water bottles, dumbbells and resistance bands are strewn around us. ‘I was just very, very disappointed in my performance,’ she sighs, pausing as she tries to articulate her feelings. ‘I know everyone’s going to say, “Why? That’s so weird.” But I actually feel like I lost. That’s just me. I always want to be the best version of me.’

It’s been five days since Ali returned from Las Vegas, where – contrary to what she’s saying – she won her debut US fight. The judges voted in favour of the Somali-born, London-bred boxer over American Mikayla Nebel, cementing her status as an undefeated professional boxer. ‘I wouldn’t say I’m undefeated; I’ve only had three [professional] fights,’ she laughs. ‘You’re still undefeated, champ!’ an eavesdropping fellow boxer shouts.

Ali quickly climbed through the ranks of amateur boxing after winning her first fight in London in 2012. In 2016, she won the English and British national titles – the first British Muslim woman to do so – and in 2018 took on Nike as a sponsor. In 2020, she made her professional debut (different boxing styles, higher stakes and payment for fights), after renowned promoter Eddie Hearn signed her to Matchroom Boxing, while Anthony Joshua took her onto the books of his 258 management label. ‘He messages a lot asking if I need anything. I haven’t gone to him for anything yet but if I need a private jet or a yacht one day, I might hit him up,’ she jokes.

She might get one, too: ‘Ramla is a true inspiration,’ Joshua says. ‘I feel privileged to be working with her. She has so much potential in the ring and has worked so hard out of it to spread positivity. She’s an incredible athlete and a wonderful person.’

The out-of-the-ring positivity Joshua references is Ali’s activism, which she fuses with her boxing. In 2018, she launched Sisters Club: a free self-defence class for vulnerable women in London, which she plans to expand nationwide. In 2019, she travelled to the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan with UNICEF, where she taught young refugee girls who had fled the conflict in Syria how to box. And she’s just written a book, Not Without A Fight, which is part-self-help, part-memoir and comes courtesy of #Merky Books, a Penguin imprint launched by Stormzy in 2018 to champion young, diverse voices.

For others, Ali is more familiar as a figure in the world of fashion than sport, thanks to her burgeoning modelling career. (She’s on the books of IMG, which also counts Gigi and Bella Hadid, Ashley Graham and Paloma Elsesser as clients.) She is undeniably beautiful, with delicate features, wide eyes and high cheekbones. Even when dressed to box, like today, with her natural curls pulled back into a sleek bun and no visible make-up, she looks flawless.

It’s no surprise that Ali’s job is to fight – whether that’s in the ring, for social justice or for wider representation in fashion. It’s in her DNA. ‘I feel like the concept has come from my mum,’ she smiles. ‘She’s the ultimate fighter; a champion. Everything my mum has been through… Obviously she’s a very sassy woman, that comes with being African, but she always comes out smiling. She’s never moaned, she’s never complained that she’s had a hard life. She just gets on with it. That is the mindset of a true warrior.’

Ali was born in Mogadishu, Somalia, and her family of nine lived in a three-storey house moments from the beach. But in the early 1990s, when she was still a baby, life was turned upside down with the outbreak of the country’s brutal civil war. Her parents were already considering joining the mass exodus of Somalis fleeing the country for safety when tragedy stuck. Ali’s eldest brother was outside playing in the garden when he was killed by a grenade. Ali doesn’t remember him. ‘I don’t remember anything from Somalia, but my mum says it’s probably a good thing because it was so traumatic.’

In the haze of grief, the family left their country, first for Mombasa, Kenya, travelling by a small sailboat on a journey that took the lives of many of the more than 200 refugee passengers on board. They stayed there for a year, relying on food rations from UNICEF aid workers while Ali’s parents worked tirelessly in the hope of coming to the UK. In November 1992, they arrived in London and applied for asylum. They were moved into temporary housing: first in Paddington, then Manor Park, East Ham, Whitechapel and finally Bethnal Green, where Ali’s parents still live today.

Due to the chaos and devastation of the war, Ali doesn’t know her exact age or birth date. She estimates she’s between 29 and 31, likely towards the latter, and has an honorary birthday of 16 September, but ‘it’s never really felt real’. Growing up, she’d get jealous of other children. ‘We weren’t really the birthday-celebrating type. My mum would get gifts, but there wasn’t a party with a cake or balloons. The way that I see it, it’s just a day, it’s just a year – it doesn’t matter. You’ve got your health, a roof over your head and food in your belly. Those are the most important things. But I’ll always accept gifts if people want to give them to me,’ she says, laughing.

After arriving in the UK, Ali’s father – who possessed multiple degrees, spoke fluent Italian and had owned his own business – found work on a building site, while her mother stayed at home to raise six children. ‘There was always food on the table, we were never in a position where the heating was off or we didn’t have hot water,’ says Ali. But, looking back, she has realised that her mother only ate her children’s leftovers, never cooking a meal for herself. At school, Ali and her siblings qualified for free meals: ‘I could never afford to take in packed lunches, but I always wanted to.’

In 2020, Ali reflected on the lifeline free school meals gave her family, and spoke out about the government’s decision to discontinue them during the school holidays. Her thoughts on Marcus Rashford, who led the ultimately successful campaign to get the decision reversed? ‘Oh, what a legend.’

At home in east London, traditional Somali culture was blended with Western influences. In her book, she writes of happy memories watching YouTube-streamed Somali soap operas with her mother, and we bond over our mutual love of Nineties Nickelodeon shows, such as Kenan & Kel, Sabrina The Teenage Witch and Sister, Sister. She listened to her older sister’s Backstreet Boys and Peter Andre albums and loved reading, her favourite book being Pride and Prejudice. Meals consisted of roti, chapatis and slow-cooked meats and her mother was house proud, covering the sofas and carpets with plastic except when guests came over. Ali wore a hijab and went to Quran classes at the local mosque. That is until one day when she was about age 11, on the way home from class, two boys blocked her way with their bikes, tore off her hijab and stamped on it, laughing. She stopped wearing it after that.

‘It’s the event that has most shaped me into who I am today,’ Ali says, looking down. ‘I was shocked, even though at the time I didn’t know it was a racist attack.’ Did she connect her decision to stop wearing a hijab with that moment? ‘Not at the time, because I was so young. I wasn’t smart enough to put the two together,’ she laughs, self-deprecatingly. Ali didn’t tell anyone what had happened, not even her parents. She still hadn’t, until writing about it in her book. Now, not wearing a hijab is a personal choice: ‘One day, when I’m ready to put it back on, I feel like I will. I do my prayers, fasting, my charitable donations. I’m very in touch with my religion and my faith.’

When Ali was a teenager, her mother became concerned when she experienced bullying in school because of her size. After a doctor told her her daughter was overweight, she bought her a junior gym membership. Ali started boxercise classes – and caught the bug. She began training at a local boxing gym, despite the warning from the coach that ‘girls don’t box’. She got better and better and started competing, all the while keeping her newfound passion a secret from her parents. They eventually found out when one of her London-based fights was broadcast locally and her brother was aghast to see his sister on screen throwing punches in the ring. Ali returned home that evening to her family sitting together in the living room: ‘It was some sort of intervention.’ Her mother cried with worry about her daughter’s safety and her decision to have a hobby that went against their values. They ordered their daughter to stop boxing and she obliged. Temporarily.

But she couldn’t stay away. She’d quit, become depressed, return and give up again when the guilt of betraying her family’s wishes got too much. ‘My boxing career has had a lot of stops and starts, much to the detriment of my career,’ she says. ‘I feel like I should be a lot further on than I am now.’

Though, years later, Ali’s family have come around, her mother still hasn’t watched her fight. The pair had an agreement that she would travel to Tokyo to watch her daughter if she competed in the Olympics this year. Unfortunately, the ongoing Covid-19 restrictions mean that, when we talk, it is looking unlikely. ‘I think it’s reckless that the Olympics is still going ahead,’ she sighs. ‘It’s obviously been a lifelong dream of mine, and I will still go and represent my country with pride, but it’s very risky.’

In spite of assumptions, given the national titles she’s won, it’s not Team GB that Ali is representing. The call-up never came, and the devastation of this spreads across Ali’s face as soon as I ask about it. ‘It was so sad. I did everything that was possibly asked of me and I never got invited to Selection Camp.’ Ali, who had trained with the GB squad in Sheffield on several occasions, explains that when a boxer wins both amateur national titles – as she did – they are usually called up for a trial with the squad. ‘There is a lot of politics involved in why [I didn’t get invited]. I don’t want to speculate, because it isn’t my place. I was really heartbroken and wanted to stop competing.’ England Boxing told ELLE that Ramla had been touted ‘as a boxer with potential’ but, at the time of selection, there were only three weight categories in women’s Olympic boxing (there are now five) and her weight was not one of them. Though she could have attempted to box at the lowest weight category, in those groups ‘there was significant competition from boxers who, at that time, were significantly more advanced in their development’. England Boxing added that it ‘wishes Ramla all the very best’.

Following a chat with a friend who had focused their efforts on competing for a country other than the UK, Ali decided to represent Somalia. To do so, she had to set up a boxing federation in the country, which was no easy feat. ‘At the time, I thought it was such a cop out – “You couldn’t get on [Team] GB so you’re doing the next best thing.” But I’m really happy about my decision.’ Her confidence has been cemented by the influx of messages she’s received from Somalis showering her with adoration and pride.

Ali only started to believe she could box full time when she met her now-husband Richard Moore, who is also her coach, sparring partner, day-to-day logistical organiser and pretty much everything else, too. As he walks through the revolving door into the gym, his friends fall about laughing, watching him struggle to carry three of Ali’s suitcases. ‘Is that a metaphor for your relationship?’ one of them jokes. He leaves us to chat, apart from one small interruption to bring Ali her 4pm snack, a healthy acai berry yoghurt pot, by the looks of it. Ali wrinkles her nose in disgust as she takes a spoonful. Yoghurt aside, she’s evidently grateful for him, glowing whenever he’s mentioned.

According to Ali, Moore pursued her. A boxer himself, he would hang around at the gym, watch her train and attempt to strike up conversation, which didn’t work. ‘Growing up getting bullied, I never had any confidence. When he started pursuing me, I thought somebody had dared him, so I never gave anything back.’ A month later, Ali relented and went to a BBQ at his house. The rest is history, she says – by which she means that, after meeting in May 2016, Moore proposed in August (by which time he had converted to Islam) and they married in October. Around this time, the couple discussed whether to buy a house or invest in Ali’s boxing career.

‘I was smart – I said we should get the house. He said, “Nah, we’re going to do the boxing.” That was all of Richard’s savings. We were this close to being completely broke when Nike came on board and started sponsoring me.’ To separate their professional and personal lives, they have a rule: ‘What happens at home, you don’t bring to the gym,’ and vice versa.

A day in the life of Ramla Ali involves a wake-up time of 8am. Moore will cook her breakfast (‘He makes all of my meals when I’m in camp, because he doesn’t want me getting obsessive over what I eat’) and then they’ll head to the track for conditioning at 10am (with packed snacks provided by Moore). They eat lunch, she’ll nap, then it’s off to the gym for her second training session of the day. They finish by eating dinner together and watching a film. It’s the same every day, apart from rest days.

Or on those days when Ali’s pursuing her other career in fashion. She developed her love of clothes and style in her early twenties when, between training and studying law at university, she worked in a shoe shop on London’s Oxford Street. ‘At 6pm, I’d toddle off to New Bond Street and walk past Dior, Coach, Chanel, window shopping and thinking, One day… Who knew I’d end up being paid to wear it?’

She recently became the face of luxury jewellery brand Cartier and she still can’t quite fathom it: ‘They want to work with me! You’ve just got to pinch yourself sometimes.’

As amateurs aren’t paid to fight, Ali is transparent about the fact that it has been modelling, not boxing, that’s allowed her to earn a living. And even now she’s turned professional, the earning potential for women is incomparable to male athletes. In 2017, Floyd Mayweather came out of retirement to pocket a reported $275 m for one fight against Conor McGregor, who earned around $85 m. A 2020 feature in The Athletic suggested that, by comparison, high-profile female boxers might be able to earn six figures, depending on the fight.

Ali is an outspoken voice in the post-#MeToo conversation about women in sport, joining high-profile gymnasts and female wrestlers who have opened up about their experiences of sexism, harassment and abuse. Ali’s book recounts an incident in her early days of training, when she was groped and sexually harassed by a coach who then forced her out of the gym after she confided in another female boxer about what had happened. With age, hindsight and an industry-spanning reckoning of how workplaces treat women, Ali can name what happened to her as abuse but at the time she blamed herself, convinced that she must have ‘led him on’.

Now, Ali uses her status to call out misogyny and racism, joining a new wave of athletes – such as Naomi Osaka, Lewis Hamilton and Raheem Sterling – who are determined to show that there are human beings behind the crowd-pleasing performers. She has a serious gripe with some of the men in boxing, whose behaviour actively discourages women from joining in. She was outraged when watching back one of her fights (as she does with each one), hearing a commentator – Ali won’t name names as she doesn’t ‘want to get anyone into trouble’ – call her a ‘beautiful girl’. On Twitter, another pundit described Ali and her opponent as ‘a model and scaffolder’. ‘You’re watching me compete, why are you not commenting on my boxing?’ she says, animatedly. ‘What does me being a model have anything to do with it? I’m a boxer. What does her being a scaffolder have anything to do with it? She’s a boxer. Give us the respect that we deserve. We’re both in the ring, it’s a dangerous sport, we’re both putting our lives on the line.’

Making boxing accessible for women is a passion of Ali’s, and it’s what’s driven her to set up Sisters Club. In the classes, Ali teaches women – several of whom are victims of domestic abuse – how to defend themselves. They’re taught how to how to throw punches effectively, to turn their hips correctly for extra momentum and power. ‘It’s for any woman, but primarily for those who don’t feel comfortable training around men,’ she explains. ‘It’s not just for Muslim women but it initially started that way because I was being pestered to find women a safe space where they could take off their hijabs. Now, it’s for any woman who is vulnerable and feels like they don’t have access to sport. A lot of the women that turn up are single mums. Would a single mum in that situation be able to afford a gym class? Not really. That’s why it’s free.’

As our allotted time draws to a close, Ali changes into her fight gear to spar. Her kit is less than pristine and she’s embarrassed. ‘At least there’s no blood on it,’ her husband jokes. If the next steps on the horizon – her book, Olympic and professional boxing, modelling (‘I want my face to be everywhere!’) – weren’t enough to be getting on with, a film about Ali’s life is in the works by Oscar-winning producer Lee Magiday, known for The Favourite. Ali says she turned down offers to buy the rights to her life story for two years, fearing the magnifying glass would be too intrusive, but she’s finally found a team that she trusts, who understand her. ‘I’m more than my story. All my years of hard work in the ring has proven that. Yes, I am a refugee. Yes, we were poor. Yes, we were living on a council estate. But I don’t want it to define me and who I am now. I want people to see past that, because I am past that. Look at me now. Undefeated, as they say.’

The September issue of ELLE hits newsstands on August 5, 2021. Inside the issue, ELLE UK launches year two of their mentoring scheme with the Social Mobility Commission to open the door to the next generation of creative talent across the UK.

HAIR: Stefan Bertin at The Wall Group. MAKE-UP: Jenny Coombs at The Wall Group using Danessa Myricks Beauty. NAILS: Michelle Humphrey at LMC Worldwide. SET DESIGN: Phoebe Shakespeare at Saint Luke Artists. FASHION ASSISTANT: Lois Adeoshun

You Might Also Like