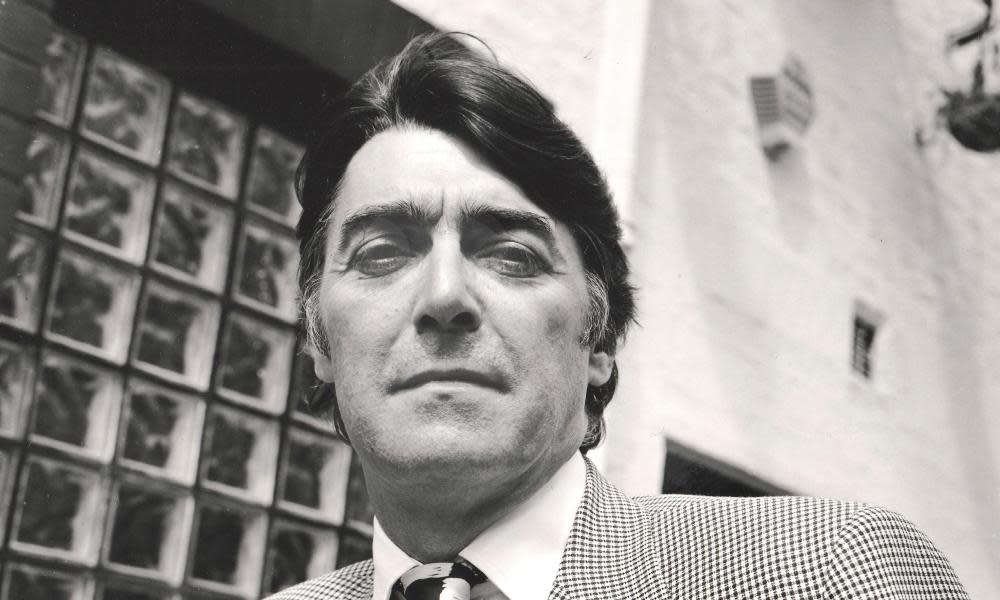

Bill Bryden obituary

David Mamet sent his script of Glengarry Glen Ross to Harold Pinter and asked what was wrong with it. Pinter said: “Nothing. All it needs is a production.” And it certainly got one of those.

Pinter had already passed the script on to Bill Bryden, who has died aged 79, a colleague and fellow associate at the National Theatre in the Peter Hall era, and Bryden’s 1983 landmark production of seedy deals among the estate agents of Chicago took off like a rocket.

Bryden had arrived at the new National on the South Bank in the mid-1970s as one of Hall’s chief allies and most distinguished directors. He created an ensemble company within the NT that has never been equalled, an unapologetically macho, brazenly hard-drinking troupe who ripped through Mamet, Eugene O’Neill and the medieval Mystery Plays of York and Wakefield as rewritten by poet Tony Harrison, creating theatrical events of high voltage and poetic density.

The Mysteries, as they became known, comprised three plays over eight years – The Passion (1977), The Nativity (1980) and Doomsday (1985) – in the small Cottesloe auditorium with promenade audiences, folk-rock music, and a hand-picked company of actors – often known as the rugby team – including Jack Shepherd, Dave Hill, Brenda Blethyn, Robert Stephens and Brian Glover (who played God in a flat cap on a forklift truck). The director John Dexter described the show as “the high point of the National’s first decade on the South Bank”.

It was the high point, too, of Bryden’s style of popular ensemble playing, fitted out with rudimentary but spectacular design and lighting by regular collaborators such as William Dudley, Hayden Griffin, Andy Phillips and Rory Dempster, and writers Harrison and Keith Dewhurst. It was performed among the audience under a constellation of twinkling orange braziers and lanterns, transferred to the reopened Lyceum theatre in 1985, almost half a century after the venue hosted its last play, John Gielgud’s 1939 Hamlet, and was filmed by Channel 4.

Bryden and his company produced 12 shows in the Cottesloe, including a second saga of magical conjuration, Flora Thompson’s Lark Rise to Candleford (adapted by Dewhurst), making contemporary joy and tragedy from a vanished agrarian world in 1870s Oxfordshire.

He had already established himself at the Royal Court, where, as a dashing, always voluble figure in the early 1970s, he brought a bracing Glaswegian fizz and glamour to new work and began assembling that glorious roster of colleagues that travelled with him down the years. His musical affiliations were with the folk-rock of Steeleye Span and the Albion Band, singers Maddy Prior and Martin Carthy, and composer John Tams.

Before arriving at the National, he was an associate director at the Edinburgh Lyceum, where he directed three extraordinary “folk” plays: his own Willie Rough (1972), about his maternal grandfather, a Clyde docker; The Bevellers (1973), by actor Roddy McMillan, recalling his days in the glass-bevelling business; and Benny Lynch (1974), about a world champion boxer on skid row in the 1930s. The latter, which he also wrote, was a pet project he was hoping to translate to the large screen, but it never happened.

There was a moment when it seemed Bryden would reignite the long-nurtured dream of a Scottish National Theatre. But when Hall came calling, he upped sticks and headed south. After 10 years at the NT, he was appointed head of drama at BBC Scotland (1984-93) – he had served on the board since 1979 – where his production triumphs included his own film, The Holy City (1985), a Glaswegian Easter Passion, and John Byrne’s delirious, delightful Tutti Frutti, (1987) starring Robbie Coltrane, Emma Thompson and Richard Wilson in a saga of low-rent rock and rollers on the road.

Bryden was born in Greenock, near Glasgow, the son of George Bryden, a bus driver and engineer, and his wife, Catherine (nee Rough), a shop assistant. He was educated at Hillend primary school and Greenock high school, finding work as a trainee at Scottish Television in 1963 and directing his first play, Shaw’s Misalliance, at the Belgrade, Coventry, in 1965.

His first London productions were at the Royal Court, where he was William Gaskill’s assistant for two years before asserting himself with a buoyant account of Keith Dewhurst’s Corunna (British soldiers fighting the French in 1808), Bertolt Brecht’s Baby Elephant with Bob Hoskins, and Edward Bond’s Passion (1971), commissioned by CND for Easter Sunday in Alexandra Palace.

In Edinburgh, at the festival in 1975, he wrote (and directed) the libretto for composer Robin Orr’s Hermiston, based on a last unfinished novel by Robert Louis Stevenson. Alongside the long-term project of The Mysteries, he and Dewhurst gave an ebullient account of The World Turned Upside Down (1978), based on Christopher Hill’s English civil war book, and he directed three remarkable American pieces: Mamet’s earlier American Buffalo, Michael Herr’s Dispatches, adapted by Bryden and the company from Herr’s devastating reports from the Vietnam war, and O’Neill’s four short plays of the sea, The Long Voyage Home.

He also served up fine revivals of O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh (Jack Shepherd as a mesmerising Hickey), Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (Mark McManus as John Proctor) and Stacy Keach in Hughie, also by O’Neill. Keach gave a towering performance as a wiped-out gambler returning, after a five-day bender, to a favoured haunt of a shabby hotel, where the old night porter, Hughie, has just died.

Keach would feature in a mid-western movie about Jesse James and his gang, which Bryden proudly co-scripted, Walter Hill’s The Long Riders (1980), alongside his brother James Keach, Dennis Quaid and his brother, Randy, and three Carradines – David, Keith and Robert.

Bryden loved westerns, and all the great Hollywood epics, and wrote a play for the National, Old Movies (1977), in which an ageing producer, played by EG Marshall, is trying to set up a biblical extravaganza. His larger exploits on the NT’s Olivier stage were not always successful – the official opening production of Carlo Goldoni’s Il Campiello, in the presence of the Queen, in 1976, was a disaster.

But he made good in the Olivier in 1983 with Dewhurst’s great rendering of the episodic mock grandeur in Cervantes’ Don Quixote, with a gloriously delusional Paul Scofield riding his Rosinante as a knackered penny farthing tricycle, oblivious to the attentive blustering of Tony Haygarth’s Sancho Panza.

And there were two unforgettably spectacular events on his home territory of the old Harland & Wolff shipyard in Govan. The Ship (1990) made drama both cinematic and realistic of the last great liner to be built on the Clyde; the ship literally slid from its timber supports away from the audience, who were abandoned to celebrate/lament the end of an era. And The Big Picnic (1994) was the Starlight Express of the first world war, the incredible vision of the Angel of Mons leading the risen dead from the muddy battlefields back home to Govan.

Along the way there were more fine productions, such as the best I have seen of Ivan Turgenev’s A Month in the Country, starring Helen Mirren and John Hurt at the Albery (now the Noël Coward) in 1994; a return to the National in 2001 with The Good Hope, a Dutch classic about the fishing industry, adapted by Lee Hall, a salty socialist tragedy with Frances de la Tour; and more bar-room poetic blather from Tennessee Williams in Small Craft Warnings at the Arcola, Dalston, in 2008.

His work in opera was limited but critically acclaimed: at Covent Garden, he directed Parsifal in 1988 and a beautiful version of Leoš Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen in 1990. And for the ENO, he directed the Olivier-award winning The Silver Tassie (2000), with music by Mark-Anthony Turnage and a libretto by Amanda Holden.

Bryden did not enjoy the best of health in the past 10 years, but he never stopped planning and writing. He was made CBE in 1993 and received honorary fellowships from Rose Bruford drama school, Queen Margaret College (now Queen Margaret University) in Edinburgh and the University of Stirling.

His first marriage, to Deborah Morris in 1971, ended in divorce in 1988. Bryden is survived by their two children, Dillon and Kate, and by his second wife, Angela Douglas (the widow of Kenneth More), whom he lived with from 1988 and married in 2009.

• William Campbell Rough Bryden, director and writer, born 12 April 1942; died 5 January 2022