Betroffenheit, Sadler’s Wells, London, review: This dance-theatre hybrid is raw, funny and profoundly, tenderly human

Betroffenheit is an overwhelming theatrical experience, a stark exploration of grief and addiction. Created by Crystal Pite and Jonathon Young, this dance-theatre hybrid is raw, funny and profoundly, tenderly human.

The word Betroffenheit means shock or impact. It is based on Young’s own tragedy, the death of his daughter and her two cousins in a fire. The accident is not explicitly shown. Instead, it fills the protagonist’s mind, both in the ways he tries to escape it and the way it cannot be escaped. Fresh from winning an Olivier award, the show has now been filmed for BBC Four.

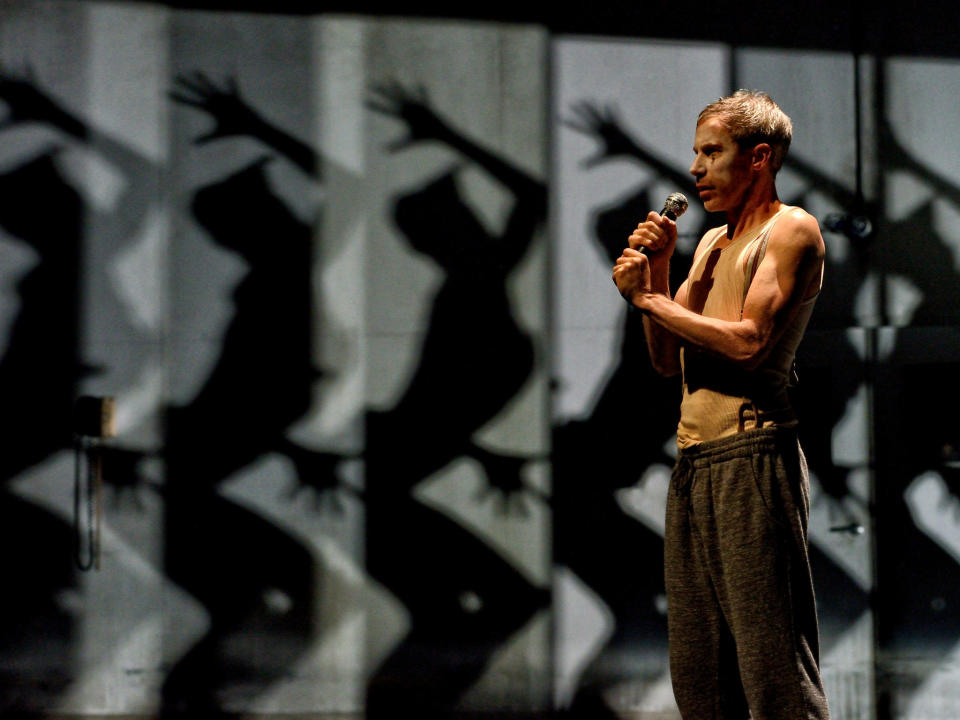

Young wrote and stars in the production, directed and choreographed by Pite. The first half takes place in a bare industrial space, the “room” that Young retreats to. His self-help routines splinter as he repeats them. Tiffany Tregarthen, a showgirl clown in sequinned knickers and whiteface makeup, scampers in with a detonator, a Wile E. Coyote figure ready to blow up his mind.

Young and Pite present addiction as a demonic Las Vegas show taking over his head, an explosion of dancers and comedians, fluttering feathered fans or luring him into performance. Young is echoed by Jermaine Spivey in a double act, a crosstalk routine given an edge of hysteria by recorded audience applause.

The performances are magnificent. Young seems both inside and outside experience, knocked out by it and making sense of it in the same breath. The dancers move as if they’re possessed. Tregarthen is an unnerving imp, all toothy grin and boneless flexibility. Spivey is silky and manipulative, purring through the shared sequences, literally making Young his puppet.

Pite takes happy dances – tap, Charleston, Latin American partner dance – and makes them terrifying. It’s all too fast, too precise, relentless and strange. The five dancers are multiplied by shadows, pushing Young to the point of collapse. When he breaks, he reveals what all this has been hiding: the reality of loss, bare and sad.

The second half uses movement to explore that open grief. The dancers are almost unrecognisable, soft and human in ordinary clothes. Their fluid steps are full of echoes, now stripped of the jazz hands energy. Young keeps protesting that he is not the victim; accepting help means accepting what has happened. In the last solo, Spivey dances that process. His limbs crumple as he finds ways to support himself, slowly and painfully holding himself up. When at last he leaves the stage, he looks both broken and hopeful.