Benedict Cumberbatch Needs to Work on His Banjo Game

Benedict Cumberbatch is a diligent researcher of the lives of his characters, both fictional and non-fictional. On the face of it, the story of Greville Wynne, the character Cumberbatch plays in his most recent film, The Courier, offered rich pickings. But there was a problem. A real-life businessman recruited by MI6 during the Cold War as a go-between with Soviet asset Oleg Penkovsky, the late Wynne had left behind two books detailing his exploits. Unfortunately, he was a compulsive liar. Much of what Wynne described was either wrong or simply couldn’t have taken place. The Courier, then, needed to be one Hollywood biopic that relied less on its source material to try and get to the truth. (When it comes to espionage, it turns out you can’t trust anyone.)

So how best to get a handle on the man?

“It’s weird,” Cumberbatch says. “Things come out of leftfield that pull you in the direction of understanding a character.”

With Greville Wynne it was his tie.

“I said ‘This tie’s in every single photograph of him. It’s what he wears on show trial, it’s what he wears when he comes out of prison, it’s what he wears before he was ever embroiled in this whole thing’. I researched it. It was a University of Nottingham Engineering Club Tie. He was never part of any Club. It’s a uniform. He’s projecting a personality. It’s an act. A bit of showmanship.”

Cumberbatch has been busy. He currently has four films awaiting release. Two for the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness and Spider-Man: No Way Home, and two others in which his love of research proved especially useful. For The Electrical Life of Louis Wain, about an eccentric Edwardian artist whose pictures of big-eyed cats playing cards, doing the washing up, etc bought him a big audience but little money, he enlisted the help of Wain’s long-time art dealer, Chris Beetles.

“I did a lot of the painting that you see in the film,” Cumberbatch says. “That is me doing it though I can’t do it with both hands [Wain was ambidextrous and painted with two hands simultaneously]. But I don’t know if anybody can. He really could. It wasn’t just a party trick.”

But he really had his work cut out on The Power of the Dog, the fairly mind-blowing Western that is the first film in thirteen years from one of the world’s great directors, Jane Campion (The Piano, Bright Star). Cumberbatch plays Phil Burbank, a swaggering ranch owner in early 20th-Century Montana who torments the wife of his younger brother, George. According to Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel, the elder Burbank is “a great reader, a taxidermist, skilled at braiding rawhide and horsehair, a solver of chess problems, a smith and metalworker, a collector of arrowheads (even fashioning arrowheads himself with greater skill than any Indian), a banjo player, a fine writer, a builder of hay-stacking beaver-slide derricks, a vivid conversationalist”.

All the horse-riding Cumberbatch was fine with, having covered that one off in the 2011 movie War Horse. “Loved it,” he says. “Wonderful just to get back in the saddle.” (“Though,” he adds, “it was a Western, so it’s a different style”.)

That just left braiding, roping, ironmongery, hide-treating, hay-stacking, whistling, whittling and the banjo. The Power of the Dog leaves you in no doubt that he became proficient in them all. He was match-fit before shooting started, taking himself off to an ironmonger on location in South Island – New Zealand standing in for the 1920s American West – hammering out a horseshoe and giving it to Campion as a good luck present.

In the book, which Campion adapted herself, Burbank doesn’t just make derricks, “hewing out the huge beams with adze and plane”. He also carves “those tiny chairs no higher than an inch in Sheraton or the style of Adam”. Such a chair has a small but significant part to play in the story, so Cumberbatch made a set of those, too.

For reasons buried deep in his past and because it is part of an image he needs to project, Phil Burbank seldom washes. So Cumberbatch followed suit.

“I wanted that layer of stink on me. I wanted people in the room to know what I smelt like. It was hard, though. It wasn’t just in rehearsals. I was going out to eat and meet friends of Jane and stuff. I was a bit embarrassed by the cleaner, in the place I was living.”

He stayed in character throughout, ominous Montana drawl intact.

“If someone forgot, on the first day, and called me Benedict, I wouldn’t move,” he says.

There were also a lot of cigarettes to be smoked – “perfectly rolled with one-hand”, as per Savage’s text.

“That was really hard,” he says. “Filterless rollies, just take after take after take. I gave myself nicotine poisoning three times. When you have to smoke a lot, it genuinely is horrible.”

Yet with all of this, as the saying goes, there is always room for improvement.

“I really wanted to become world class at the banjo,” Cumberbatch says. “And I’m very much not. I’m very far off.”

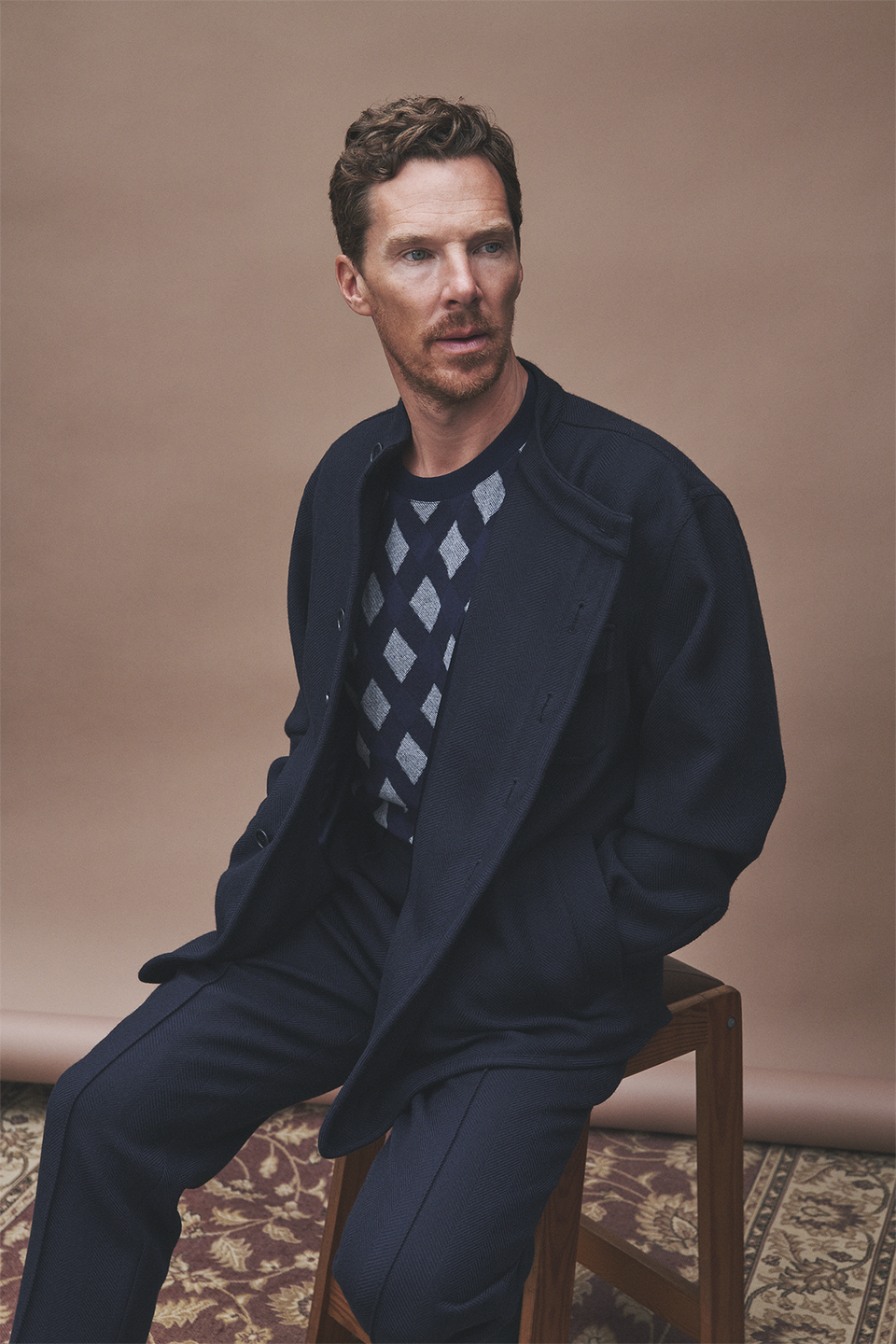

Benedict Cumberbatch arrives promptly one July morning to have his photograph taken for this article. He stands in the garden in a windcheater and trainers talking on his phone.

Even by his notably productive standards, he’s had a lot on.

“People will write books about this one day,” he says. “How the hell films managed to get made with everything that was going on in the world.”

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness was almost entirely filmed in a studio in Surrey, off the A30, in lockdown.

“They had the gold standard in test and trace,” he says. “They would test us every other day and temperature test every day when we came in. If you had any cold or cough or were feeling under the weather, they were very on it. But the work environment was pretty grim compared to the norm, everyone zoned and masked. It was hard graft. But there was a lot of appreciation for how lucky we were. Five hundred-plus crew members coming back and all testing negative at Christmas. The dedication was admirable.”

The Power of the Dog began shooting in New Zealand in January 2020. Then production was shut down until June.

“We weren’t turning on our television every day or looking at our phones for news feeds. It was not a growing concern,” he says. “Then when we got to Auckland it was, like, ‘Oh. It’s not just that it’s not crazy here. It’s actually crazy everywhere you need to get to, to get home’.”

A further complication was that Cumberbatch was travelling with two octogenarians in tow – his parents.

“[Coronavirus] was just coming and coming and coming and Boris Johnson was still going [Johnson’s voice] ‘I’m hugging everyone, I’m kissing everyone, I’m licking door handles. Oh no, I’m not – now I’m in a hazmat suit’. You could see it was going to hit very hard in the UK because of the ineptitude. So, I just went ‘You’re staying here’. I couldn’t let them go.”

Cumberbatch gets involved in the photos, suggesting set-ups, noticing when the sunlight’s changed, checking whether a certain watch wouldn’t look better with a different top.

“When you’re standing on the red carpet and they’re going ‘To me! To me! To me! That’s horrible,” he says. “This is a bit more creative.”

Afterwards he settles down with a chocolate brownie and a ginger beer, news that will no doubt send shockwaves across the corner of the internet dedicated to whether Benedict Cumberbatch is or is not a vegan. (But then there seems to be a corner of the internet dedicated to anything and everything to do with Benedict Cumberbatch.)

“I was for about 18 months,” he confirms. “I applaud people who are vegan and I enjoyed my journey with it, but it [non-vegan food] just crept back into my life.”

Of more concern now is sustainability. The outfits he wears in these pictures have, for the most part, been chosen with their environmental footprint in mind, with his input.

“Unsustainable practises… there is another way of doing it,” he says. “You can think of a solution and really do something, rather than despair at the problem.”

Cumberbatch is a doer. His friend Keira Knightley once said that he never chooses the easy path.

He laughs. “Pushing that boulder up the hill. I mean… I like a challenge,” he says.

Why does he think that is?

“I really enjoy my work. When I do work, I want to work hard. It has to be worth leaving my family [his wife, the theatre director Sophie Hunter and their three boys] and home for, to do. To make them… Oh, this sounds weird but I guess to validate me not being there. And If I can get away with a new skill and call it work, lucky me, you know? That saves me a few night classes or, you know, time I don’t have.”

Still, there’s a difference between wanting to learn a new skill and wanting to become world-class at the banjo.

“But on the side of the set it’s very, very good,” he says. “It’s like giving an actor something to eat, like Marlon Brando said. You’re constantly taking the nervous energy away. It did mean it was slightly antisocial, but you know, whatever. I don’t need to be gossiping around the coffee urn on every shoot.”

In 72-hours he’ll fly to LA for two weeks’ reshoots on Spider-Man: No Way Home.

“I think my primary motivation is that I just really, really enjoy it,” he says. “And I like the idea that I might be getting better at it.”

It’s hard to imagine that anyone who sees The Power of The Dog could disagree with that. It is outstanding in every way – not just Cumberbatch but Jesse Plemons as George Burbank, Kirsten Dunst as Rose, the woman he marries, and Kodi Smit-McPhee as Peter, her son. It looks and sounds and feels incredible. You can hear every squeak of leather, feel the prairie wind blow in as the melodrama ratchets up.

“I spent a really long time trying to work out the languaging for it,” says Jane Campion. “How we were going to photograph it, frame it. And have a rule of utter economy. Like, try and keep those shots going for as long as we could and try and not make it frivolous. Or have flourishes that were unneeded.”

The book the film is based on is not well-known, selling “no more than a few thousand copies” on its release, notes Annie Proulx in her afterward to a 2oo1 reprint. But in Burbank it features, she says, “one of the meanest characters in American literature”.

“The book kept coming back to me,” Campion says. “And if something haunts you I think you’ve got to let nature happen. I felt ‘this should be done’.”

As for her leading man: “We pushed each other along. He was a really great collaborator with high expectations and ideals. Practical skills? Oh my God… he was dazzling.”

I ask Cumberbatch if he’s ever signed up for a job and thought “I’ll just busk it”.

“Yeah,” he says, immediately. “I’m doing it tonight.”

He’s talking about Letters Live, an event at which famous (and some non-famous) names read out thought-provoking historical letters, a mix of the serious and silly, the profane and the political. Audiences never know what they’re going to get, the celebrity bingo aspect being part of the appeal. Ian McKellen reading Roald Dahl, Gillian Anderson reading Jackie Kennedy, and so on. Cumberbatch has been a regular since the first show in a theatre in 2013 and his production company, SunnyMarch, now has a hand in shaping it. (It also produced The Courier and The Electrical Life of Louis Wain, among others.)

“I really haven’t practised,” he says.

Tonight, he reads a letter written by a dying miner to his wife in a 1902 mining disaster, the worst in Tennessee’s history, the miner’s 14-year-old son next to him. Then one from a resident asking for his ban from the Empress Hotel in British Columbia to be lifted, three sides of increasingly far-fetched excuses that had gone viral in 2018. Four lines from Hunter S Thompson to a literary agent who turned him down. And a letter from Nick Cave in reply to someone called Cynthia, asking for advice on grief. Cave’s son Arthur died in 2015. “I feel the presence of my son, all around, but he may not be there,” he writes. “I hear him talk to me, parent me, guide me, though he may not be there”.

Afterwards I find Cumberbatch in the bar with his wife, some of the other performers and friends. He says could feel himself getting overcome by the first letter, its meaning only coming into focus as he read it aloud.

“I couldn’t help it,” he says. “I didn’t realise about his son. I told you I hadn’t practised. So, the joy of doing the Empress Hotel…”

Then there was Nick Cave. Cumberbatch is a formidable mimic, but Cave’s letter was the only one he chose to perform in his own voice.

“I do quite a good Nick Cave, I was very tempted to...” he says. “But I just thought ‘I can’t’. He’s too big a presence.”

Cave has Louis Wain paintings up on the walls of his Brighton home. He also has a cameo in The Electrical Life… playing HG Wells.

“It’s a bit of a Nick Cave fest,” Cumberbatch says. “Nick Cave is a master, he really is.”

A conversation about playing real people.

Of the many compelling characters Cumberbatch has taken on, Sherlock Holmes, Alan Turing, Stephen Hawking, WWI soldier Colonel Mackenzie, Hamlet, Frankenstein, Tinker Taylor Soldier Spy’s Peter Guillam, the only one who is both real and still alive, is Dominic Cummings. I wonder if that changed his approach?

He immediately points out my mistake.

“Patrick Melrose is still alive,” he says. “Billy Bulger, I think, has died. Julian Assange is still alive… you know, Khan’s on ice, so that’s open for debate…”

(For the record, William ‘Billy’ Bulger the American lawyer he played in 2015’s Black Mass, is 87 and still alive at the time of writing. Patrick Melrose, who he played in 2018’s sublime TV miniseries, is based on the semi-autobiographical novels of Edward St Aubyn, 61 and still around. Khan Noonien Singh, who he played in 2013’s Star Trek into Darkness, is a genetically-engineered augmented superhuman from the 23rd Century, who the crew of the USS Enterprise put into cryogenic sleep. He’s got me on Assange.)

Still, he takes my point?

“I take your point… in a way. But don’t think I have just played historical characters.”

It’s difficult to gauge whether he’s actually quite put out.

“What’s the nature of the question? I don’t think it’s a very strong thesis.”

I really wanted to ask about Cummings, I say. That having re-watched Brexit: The Uncivil War, 2019’s TV drama about the Vote Leave campaign, in the light of his recent disclosures and allegations, it seemed even more eerily on the money. What did he make of it all?

“I tease James [Graham, the writer] about every headline that pops up, you know?” he says. “Going ‘We’re now on sequel number five’. It’s been extraordinary to watch a character who was pretty unknown in the backrooms of the corridors of power come to the forefront in such an extraordinary way. I don’t really want to judge him publicly.”

But he met Cummings for the role. He must have watched his “revenge” with particular interest?

“They’re contentious figures around very complex issues and yes, I have my own opinions. But I think it’s far more important that other people express those things than me. I don’t have any insight beyond the moments in time that I try to get something right of them in a portrayal. I’m not the go-to expert on this.”

There is, I suggest, one more still-living famous name he’s played this year. Morrissey, on The Simpsons.

“That was not Morrissey!”

In the episode Panic on The Streets of Springfield, Lisa becomes besotted by depressed English singer Quilloughby and his band The Snuffs, authors of ‘Hamburger Homicide’, ‘How Late Is Then?’ and ‘Everyone Is Horrid Except Me (And Possibly You)’. Later, she goes to a music festival and finds the bequiffed singer has turned into an overweight bigot.

You do sound a lot like him, and sing a lot like him.

“Oh, thank you,” he says. “I take it as a compliment because I love the way he sings and sounds.”

Morrissey was less keen. His manager issued a sprawling statement, saying, among many other things, that The Simpsons had taken “a turn for the worse”, that showing the singer with his belly hanging out of his shirt (“when he has never looked like that at any point in his career”) was hurtful and asking, of Cumberbatch “Could he be that hard up for cash that he would agree to bad rap another artist that harshly?” saying he should “speak up”. “Does he even have enough balls to do that?”

“No comment,” Cumberbatch says, probably for the best.

Having watched or re-watched a sizeable but still incomplete sample of his work looking for clues and context and connections – 21 roles – I fear that the most insightful observation I can manage to report back is that Benedict Cumberbatch is simply a terrific actor.

There was a time when even he had to concede that he was falling victim to “playing slightly asexual, sociopathic intellectuals”, as he told Radio Times in 2011. But that is simply no longer true, if it ever really was in the first place.

In 12 Years A Slave there’s a plantation owner called George Ford with Cumberbatch’s face and body, but the voice, posture and movement is of someone else entirely. In Atonement there’s an oily paedophile named Paul Marshall, someone the film’s credits insist is Cumberbatch, but I fear there must have been some terrible mix-up. On the YouTube comments under The Fifth Estate trailer, his Julian Assange film (still alive, 50!), the verdict is unanimous.

“As an Australian I must say that Benedict’s accent in this movie is an outstanding achievement! Even the highest ranked actors can’t pull it off like he did”

“For a British bloke he pulls of the aussie accent magnificently”

“His accent is sooo gooood omg”

More perplexing still, it’s not like Cumberbatch has a particularly forgettable face, as all those “sexy otter” memes and Sid-The-Sloth-from-Ice-Age jokes suggest. But the only time you think “Oh, there’s that bloke from Sherlock” is when you’re watching Sherlock.

“He’s uniquely chameleon-like,” says Dominic Cooke, who directed Cumberbatch in The Courier and 2016’s BBC production of Richard III. “It is possible to transform physically, and he takes on a completely different physical space and appearance. He did two [stage] shows in the space of a couple of years, Frankenstein[directed by Danny Boyle, 2011, where Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller audaciously took alternate nights playing Frankenstein/ The Creature], which was like a piece of modern dance, he was naked for the first 20 minutes, throwing himself around the stage. The other was a really tight Terence Rattigan play [After the Dance, 2010, directed by Thea Sharrock] where he was very vertical and ‘held’, and I said to him ‘I cannot imagine another actor on the planet who could do both of those things as well as you did them’.”

“He’s got such a strong imagination, like a child,” says Claire Foy, who has played Cumberbatch’s on-screen wife twice, once in 2011 drama Wreckers and again in The Electrical Life of Louis Wain. “There’s an element to him that is so willing to go into a scenario and see what happens. And that really is really rare. That’s not how I am with acting, and it’s amazing to be around. My proudest thing was watching him be Patrick Melrose. Because that was his whole idea [another SunnyMarch production]. Just to watch him ‘go’. To see him be let off and not have to be a conventional leading man. It’s amazing to see an actor do what they want to do. He could be small; he could be big and bombastic. He could be all the colours of the rainbow.”

“Look at him in Black Mass, playing Johnny Depp’s brother,” says Edward Berger, who directed Patrick Melrose and will work with Cumberbatch again next year on a Netflix miniseries of The 39 Steps. “It’s a much smaller role [than Depp’s]. But the deep voice, the way he performs… He will never give you a boring performance, and that’s part of the secret. ‘How can I stand out? How can I make the audience remember the scene?’”

“Every actor has their process,” says Will Sharpe, director of The Electrical Life of Louis Wain. “When we rehearsed, he was super-comprehensive. Interrogating every footstep, every shoulder-turn, every stroke of the pencil. But on set, he leaves it at the door. He becomes more instinctive, but he has all the knowledge there.”

Before playing Dominic Cummings, Cumberbatch went round to his house for dinner. Cummings’ wife, the Spectator journalist Mary Wakefield, wrote about it.

“He was friendly, curious – but he hadn’t come to judge Dom. He’d come to become him,” she said.

She made vegan pie (she’d heard a rumour). When Cumberbatch arrived he declined alcohol on the grounds he didn’t really drink and assumed “what I imagine is a very Cumberbatchian pose” – legs underneath him, head up, leaning forward. Two hours later he was reclining with a glass of red wine, “just like Dom”.

“By 1am he was a mirror image of his subject. Both men reclining, each with an arm behind his head.”

Later, she showed her two-year-old a photo of Cumberbatch on the Brexit set.

“Dada,” he reportedly said. “That’s Dada, Mum.”

Cumberbatch made his public debut in the Daily Mirror, under the sell ‘Wanda’s Little Wonder’, at four days old. His parents, Wanda Ventham and Timothy Carlton, are actors. Mum appeared in West End farces, Seventies TV staples The Saint and The Likely Lads and plays by John Osborne and Fay Weldon. Dad was a regular at London’s Royal Court and appeared in dozens of well-known TV shows, from Cold Comfort Farm to Foyle’s War.

More recently they appeared together, as Sherlock’s parents, in Sherlock.

I ask Cumberbatch what he was like when he was young.

“At what age?”

Whatever comes to mind.

“I was very inquisitive. I was very talkative. Slightly eccentric, I think. An old soul, as one of my teachers described me. I had a great amount of energy. I was an only child, so I loathed conflict.”

That’s an only child thing?

“Yeah, it kicks off all the time at home now. Not if you’re an only child. You’re not used to resistance. You kind of avoid it. I still don’t like conflict.”

School, he says, sorted him out.

“I was lucky enough to be in an environment [public school] that focused it into craft and acting and music and rugby and other sports. As opposed to going ‘This is a problem child, we need to do something about him’. I think I was desperately insecure for all sorts of reasons and tried to compensate for that. I was petrified by the idea of what other people thought of me.”

That’s why people become actors.

“Oh, there’s any number of reasons. Both my parents were, and I loved watching it.”

I ask if famous faces off the telly often came round to their house.

“To a degree. But we very, very, very rarely entertained. But, you know, they [his parents] were falling in and out of companies of film productions, or film shoots that were coming to an end. I remember wrap parties. But it wasn’t like Stella Street. I had the experience of my mum being recognised in the frozen peas section. That’s what I thought fame was.”

Your mum has said that as a teenager you’d write letters home saying you were “blissfully happy”.

“Maybe my parents said that! I think I was, you know? I mean, there’s a lot to examine with childhood, isn’t there? I have to say, not to be too rose-tinted about it, I genuinely had a really good time at my boarding school. It was like having a band of brothers. It was like that thing of, ‘Oh, this is what family life can be like’. And then obviously from 13 onwards, and adolescence, it was like ‘Oh, this is ridiculous. Where are the women? And where is the world?’ I was very wary of how rare the air I was breathing was.”

I ask if he finds acting hard.

“I’ve got nothing to compare it to, so I don’t know. I enjoy the things that are challenging about it… so I wouldn't say it’s hard. That’s such a loaded question. The reality of how people get into acting and have a career in it, that’s hard. Doing it is a joy. I think any actor would agree with that.”

You do seem to be working at capacity.

“I’m kind of easing out of that now, where I always wanted to live a life less ordinary. A couple of flirts with mortality made me go ‘I really want to make the most of this brief, insignificant moment to do something’.”

Cumberbatch is referring to a time in South Africa in 2004, when he and two friends were bundled into the boot of a car and held at gunpoint. There was also a gap year incident at a Tibetan Buddhist monastery, in which he nearly died of dehydration.

An armchair psychologist would certainly spot a link there.

“It’s very ‘armchair’. Anyone can draw that. Yeah, absolutely. Time is precious and if you have something that threatens your time you immediately see why.”

“Fame is harder,” he says. “Fame is much harder, I think.”

At 9pm on July 25 2010, at the age of 34, Cumberbatch went from a well-regarded actor doing “small parts in big films”, to becoming literally famous overnight. From Episode One Sherlock was giddily and globally successful and Cumberbatch inspired a level of devotion that can be hard to get your head around. By any measure he has dealt with it exceptionally well.

“I worked with him just before he did Sherlock and I remember thinking ‘Oh my God, you’re going to get really, really famous’,” says Claire Foy. “‘This is going to change your life’. I always felt with Ben, ‘That man could never walk into a room and be ordinary, an everyman in the room’. Because he looks so extraordinary. You notice him, wherever he is. So it was sort of on the cards.”

“Sherlock was essentially the perfect match of actor and part,” says Mark Gatiss, its co-creator and writer. “Having taken the plunge on a modern-day Sherlock Holmes, everything about Benedict, his age, his look, his ‘otherness’ marked him out. We drew up a huge list of possible Sherlocks but, in the end, we saw no-one but him.”

History suggests that it was his repulsive Atonement turn – a small part in a big film, a fine example of how to make the audience remember the scene – that landed Cumberbatch the gig as the high-functioning sociopath detective.

Gatiss says that’s half-right.

“Steve Moffat and Sue Vertue [co-creator/writer, and producer respectively] had just watched Atonement when I texted saying ‘What about Benedict Cumberbatch?’ I’d worked with Ben on Starter for 10 [the 2006 film about University Challenge. Cumberbatch played the stuck-up team captain, Gatiss was Bamber Gascoigne] and knew him a little bit. But Atonement made a huge impression on us all.”

Gatiss says he’s asked every day if they’ll ever be more Sherlock.

I ask Cumberbatch if he’d like to put a percentage chance on it.

“It wouldn’t be fair on anyone else involved – I’m not going to be drawn into that. No, no, no.”

Come on.

“Oh look, I still say never say never. You know, I really like that character… it’s just, the circumstances need to be right and I think maybe it’s too soon now to see it have another life. I think, wonderful as it is, it’s had its moment for now. But that’s not to say it wouldn’t have another iteration in the future.”

So, if the team cast a new Sherlock and Dr Watson, he’d give it his blessing?

Here he draws the line.

“That’s not for me to comment on,” he says.

Director Dominic Cooke thinks Sherlock came at the right time for Cumberbatch. “He had a long time just being a very good actor and getting on with it. Emotionally, he was mature by the time he got to the pressures of success. I think he quite enjoys it – he enjoys it more than a lot of British actors. He curates it quite carefully, like an old-fashioned star.”

Cooke recalls a reception the pair attended after the burial service for Richard III at Leicester Cathedral in 2015, the king’s body having been discovered buried under a car park. Cumberbatch read a commissioned poem by Carol Ann Duffy.

“It was like a nature documentary when they realised he was there – that flurry of activity.”

A trickle of autograph and photo requests turned into a flood.

“It became intense, and he did quite a lot of it, and then he just said “I’m sorry, I’m not doing anymore now because I’m going to talk to my friend’. He wasn’t defensive or stressed out, and everyone got it. I was very impressed with that.”

Cumberbatch remembers doing Frankenstein at the National Theatre and realising that the same people were in the front row every night. They’d come from China. He asked them how on Earth they could afford the time and money. “Oh, it doesn’t matter,” they said. “We love you.”

I don’t live too far from Cumberbatch in north London and sometimes I see him out for a run, or with his family. He’s not there anymore but for ages I thought he lived on Shirlock Road, a coincidence I found disproportionately amusing (he actually lived one street across).

When I mention this to him in passing, he says that I wasn’t the only one.

“Lots of people used to come and pose there, in costume. I’d be, like, ‘I think I’d better go the other way. Before they see me’.”

It’s a fool’s errand to try and put your finger on why one person is more popular than another, let alone to try and assess the situation if you actually are that person. But Cumberbatch is so hysterically loved that I ask him if he stops to wonder why.

His answer is notable for its peculiarity and its length, and perhaps for something of what it reveals of how he sees himself, compared to how I suspect others might see him. This is what he says.

“No. I’d hazard a guess that sometimes it’s because I’m very keen to…”

He starts again.

“I’m easy with promoting my failings, and that I’m just trying to do it and fail better, at whatever it is. Life principals. Advocacy work. Privacy. All of that. I don’t know. I really don’t want to say these things because it becomes about self-appraisal and it sounds like I’m blowing my own trumpet. But I try to keep a balance of certainty in who I am. And also an empathy for others, to try and be an open human being, I guess. So hopefully I keep everyone surprised and everyone, I suppose, who are that devoted… also people who are dismissive as well, there’s all sorts of voices out there, when you get to the sort of exposure I’ve had, and I’m aware of that as much as I’m aware of the devotion – I think people are loyal to me because, and maybe I say this with good intentions, but I try to improve. And like they say in the old Samuel Beckett paraphrase, fail better.”

In 2014 Cumberbatch joined Marvel as Doctor Strange, Sorcerer Supreme, primary protector of Earth against magical and mystical threats. His friend Tom Hiddleston had signed up three years earlier, in the role of Loki, God of Mischief – Thor’s archenemy and adoptive brother.

“He didn’t ask for advice,” Hiddleston says. “And he didn’t need it! He had already worked on a huge scale on Star Trek: Into Darkness and Sherlock was a global phenomenon. Over the ten or so years I’ve known him what stands out is his limitless curiosity. He’s keenly aware that life is short and precious, and his range comes from the depth of his internal world – we contain multitudes – and his energy. I love his Doctor Strange, I think it’s terrific.”

I ask Cumberbatch: did Marvel approach him?

“Yes, yes they did.”

And how quickly did you say yes?

“I kind of had my doubts about it, from just going into the comics. I thought ‘This is a very dated, sexist character’. And it’s very tied up in that crossover, that kind of East meets West occultism movement of the Sixties and Seventies.”

He was a Vietnam-era pulp character. Ken Kesey was into him.

“Yeah, yeah. And then they sort of sold me on the bigger picture, on ‘Oh no, don’t worry, this will be very much a character of his time. And, yes, he has attitude problems… but this is what we envisage’.”

Cumberbatch met with writer-director Scott Derrickson, known for his sickly horror movies, and said yes.

“And then I realised ‘Oh fuck, I can’t do it’,” he says. “I promised to do Hamlet [at the Barbican]. It’s all set-up, the theatre’s booked, I can’t do it when you want to shoot it.”

So Marvel moved the whole shoot back six months, squeezing a year’s allotted postproduction into half that time.

“They flirted with a couple of other options, then they came back and said ‘We don’t want anyone else to do it’.”

One of the impressive things on the very long list of impressive things Marvel Studios has pulled off is that it doesn’t just make popular movies out of popular comic book characters, it makes popular movies out of comic book characters no one’s heard of. There presumably are comics fans whose favourite book is Guardians of The Galaxy, originally conceived the late Sixties as a group of super-guerrillas “fighting Russians and Red Chinese who had taken over and divided the USA” but you’ve got to assume they’re in the minority.

Doctor Strange wasn’t exactly Krypto the Wonder Dog. But he wasn’t Iron Man either. (The website Comic Vine ranks Strange at Number 37 in a list of Top 100 Marvel Superheroes. Thirty-six places below Spider-Man.)

“Completely,” says Cumberbatch. “I’ve got the Second Album Fear with this one, like anyone should, because the first one was such a riotous success and he’s become a much-loved character.”

He thinks about this.

“They’re very good at exceeding expectations, when expectations are low. I think it’s always harder to exceed them when they’re high. I’m not saying they make them low. ‘We’re going to do Ant-Man!’ It’s just the way they make these things work. On paper you think ‘Is that exciting?’ They’re starting to take more risks now, I think. I mean, their directors are very tied into the house style. But, you know, Taika Waititi, they were, like, ‘Are we…? Is this going to work?’ And it’s fucking so funny, Thor: Ragnarok.”

You must be popular at children’s parties now.

“Not at the age range I’m going to.”

Aren’t a couple of your kids the perfect age?

“Yeah… if you’re aware I’m Doctor Strange. But I do look quite different from him.”

In fact, he has appeared as Doctor Strange at a kids’ party, in a Jimmy Kimmel Live sketch. Kimmel mistakenly books the sorcerer as a magician, with fairly amusing results.

“The one time I’ve ever played him outside of the [Marvel] world,” Cumberbatch says. “[The kids] really didn’t know who I was. And my abilities as the Sorcerer Supreme weren’t really appreciated by toddlers on a sugar high.”

The Spider-Man: No Way Home trailer, which gives almost equal billing to Spider-Man and Doctor Strange, was watched 335.5m times in its first 24 hours, a record that gives it fair dibs on the claim of being the most anticipated movie ever made. The previous record, now comfortably smashed, was held by Avengers: Endgame, which went on to become the highest-grossing movie ever made.

Christian Bale, Tilda Swinton, Anthony Hopkins… it’s harder to find a first-rate actor who hasn’t done a superhero movie now. But when they’re on-set in their costumes, when the Avengers are all assembled, don’t they ever start giggling?

“All the time when you’re making those movies are pinch-yourself moments,” says Cumberbatch, strategically misunderstanding. “I’m never over the giddy nature of working opposite Spider-Man. It’s pretty cool.”

So no one’s ever said ‘We’re middle-aged men! This isn’t what we went to Rada for?’

“Yeah, but you go into it, and you commit to it and it’s daft. But it’s also really enjoyable and intoxicating and should be celebrated as well and treated for what it is, which is fun.”

Another morning, another interview.

Cumberbatch sits in a chair being made up for the Hollywood Reporter (the magazine’s eventual coverline: ‘The Age of Cumberbatch’) and squints at himself in the mirror, his lightly tanned face illuminated by lightbulbs.

He’s back from Los Angeles, from finishing off Spider-Man: No Way Home and fizzing with actorly enthusiasm about Tom Holland.

“I managed to skate and surf and had a lot of time with Tom Holland being utterly, utterly gobsmackingly brilliant. He’s just the real deal.”

When we first spoke, it was the morning after he’d seen The Power of the Dog for the first time. Now he’s had some time to process his thoughts.

“It leaves an indelible mark,” he says. “When you’re crafting a character like that and going deep into your psyche, it asks questions of you both. And gives you a sense of sympathy and reverence for that character. He wasn’t a monster. He was somebody who was trying to lead an authentic life. And you want the commitment to really fulfil the expectation of the material, both for you and for the people who employed you.

“I’ve always looked at my career as a form of higher education,” he says. “It’s a wonderful thing to be able to do in the name of work.”

Cumberbatch isn’t one to keep mementos from sets: “I never like being a tourist or a voyeur of my own work,” he says.

But there was something he needed to hold on to from this one, to not let the experience go. To enshrine it a little bit. So, he is now the proud owner of a set of tiny wooden chairs in in the style of Adam, no higher than an inch. The ones he made himself, of course.

The Power of the Dog is in cinemas on 17 November and on Netflix from 1 December

A version of this article appears in the Winter 2021 edition of Esquire, on sale now

You Might Also Like