The Australian book to read next: A Cartload of Clay by George Johnston

I frequently reread the Australian novels of my youth – and few more so than George Johnston’s autobiographical “Meredith Trilogy” of My Brother Jack, Clean Straw for Nothing and A Cartload of Clay.

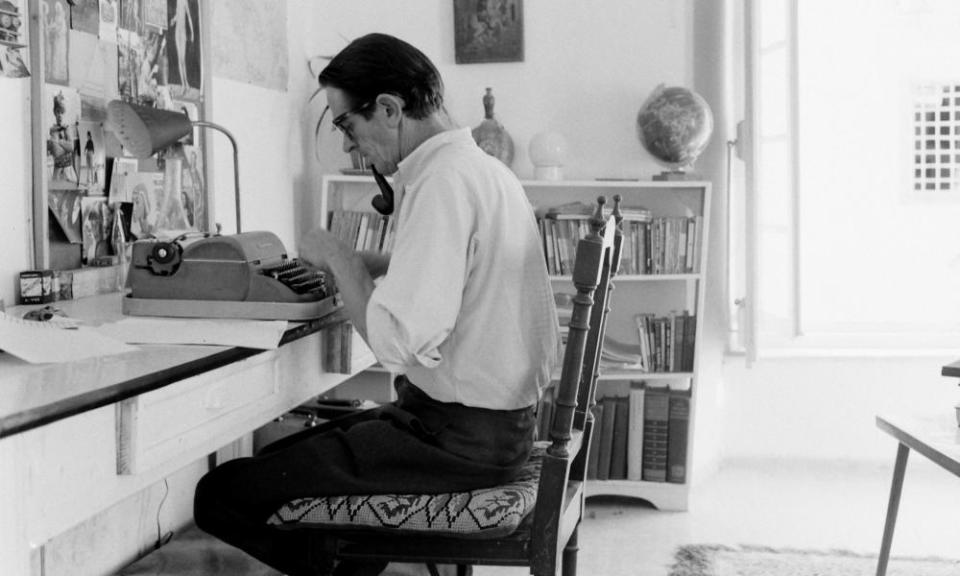

The first two, which were published in 1964 and 1969 and both won him the Miles Franklin, have certainly eclipsed the third in national memory. But for me A Cartload of Clay – unfinished when Johnston died, 50 years ago this month – emerges with rereading as equally compelling, and as the most stylistically elegant and, without doubt, melancholic, of the trilogy.

The protagonist of the three books, David Meredith, is the barely disguised author, and his novelistic wife, Cressida Morley, Johnston’s own: the Australian writer Charmian Clift.

The first two novels chart the progress of schoolboy David from dreary first world war Melbourne suburbia, through his rise as a dashing newspaper reporter and war correspondent and his extramarital affair with the beautiful young Cressida. Their mutual disenchantment with post-second world war Australia traces Johnston and Clift’s escape, first to London and on to the Greek island of Hydra where, as the mainstays of expatriate aestheticism, they raised children, wrote diligently, and drank with equal vigour while entwining themselves in the social and marital intrigues of the foreign bohemian community.

Related: My Brother Jack at 50 – the novel of a man whose whole life led up to it

Johnston (ill with tuberculosis and after a lifetime of hard living), Clift and their three children returned to Australia in time for publication of My Brother Jack and the writerly fame that had eluded him. They settled in Raglan Street, Mosman, where Johnston evoked Greek island life in Clean Straw as vividly as he had evoked pre- and post-second world war Melbourne and Sydney from Greece in My Brother Jack.

Both somehow brought enormous discipline to their writing amid their alcoholic chaos and rows. Clift, an exceptional novelist in her own right, wrote a popular column for the Sydney Morning Herald. She’d been deeply anxious about Johnston’s (“unflinching” but cruel) depiction of Cressida’s marital betrayal of Meredith on the island.

Which brings us to A Cartload of Clay and Meredith’s mirroring of Johnston: old and invalid before his time back in Australia, widowed after Cressida’s suicide with barbiturates he’d kept for when his time came. (Clift, just shy of 46, killed herself with Johnston’s medication a month before the publication of Clean Straw for Nothing.)

Meredith, the expatriate returned to home-country literary acclaim, is counting his breaths and contemplating a radically new Australia and his life (the significant past, and what little remains) while wandering from his house in Inkerman Street, Northleigh, his novelistic Mosman. Short of breath, he rests at a bus stop while rehearsing a walk to the nearby church for his daughter’s forthcoming wedding.

He cogitates in the sunshine about his wartime experiences in Kunming, a lost love affair and his warm friendship with the poet Weng Yiduo. His mind dances from childhood in Melbourne to the Meredith family’s time on the Greek island – and to Cressida’s recent sudden death. He ponders generously the “youth” generation, exemplified by his long-haired poet son Julian (Johnston’s boy Martin became a celebrated poet). Meanwhile the “Ocker” he encounters embodies the complacency, ignorant self-assuredness and anti-intellectualism that Donald Horne identified in his 1964 polemic, The Lucky Country.

While the first two novels show us an Australia of two world wars, unfamiliar to many living readers, Meredith’s 1970 is an oddly nostalgic and even quaint place, where men drink tubes and you call to get a “chap” around to fix the window Julian accidentally broke. It is real. But it’s also a reminder of the acute social change and optimism, of tensions between an old and a new Australia, as the country shrugged off Menzian conservatism. Here you realise that in those three novels Johnston charted a view of Australian change across almost the first 70 years of the federation.

In his ennui, Meredith seems at peace with his looming end while Northleigh and the rapidly changing society outside is bathed in sunshine.

Johnston died before Meredith. He died on 22 July 1970 – two days after turning 58.

Johnston biographer Garry Kinnane writes: “As David Meredith and George Johnston grow closer together in A Cartload of Clay, their identities become indistinguishable. In this state, the only fitting, indeed the only possible end to Meredith’s journey is the end of his creator. Just as in autobiography, the most complete form of ending in autobiographical fiction is the unfinished work, in which the final interruption to the self-exploration has been made by death itself.”

So it is with A Cartload of Clay. Its postscript is more poignant. Johnston and Clift’s daughter Shane suicided in 1974. Johnston’s daughter by his first marriage, Gae, fatally overdosed in 1988. Martin died of alcoholism aged 42 in 1990. Only the youngest son, Hydra-born Jason, lives on.

• Paul Daley’s novel Jesustown is being published by Allen & Unwin in 2021