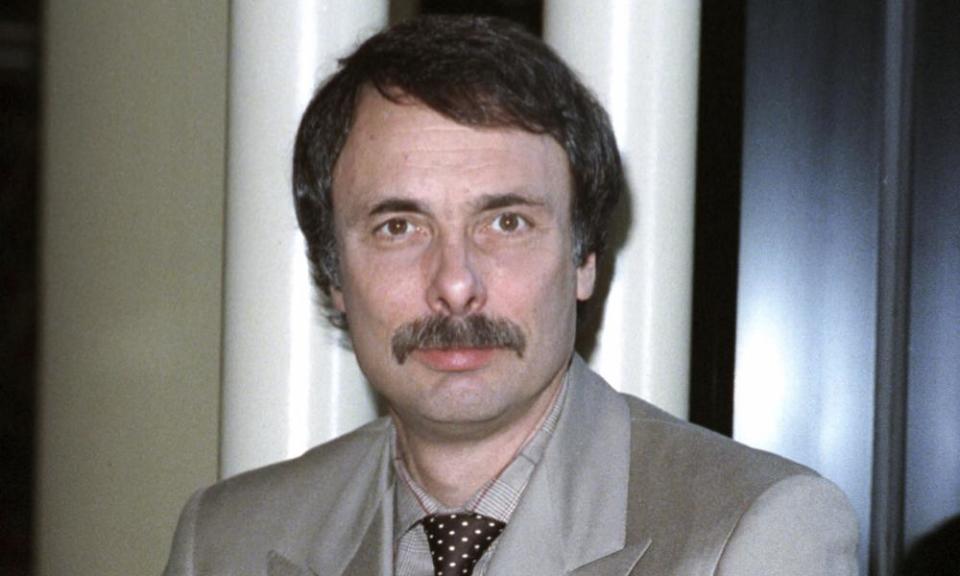

Arthur Kopit obituary

It was the fate of Arthur Kopit, who has died aged 83 from progressive dementia, to be labelled in theatrical dictionaries as a serious and inventive playwright who rarely achieved popular acceptance. His biggest success came as the librettist of the Broadway musical Nine (1982) – a classy elaboration of Fellini’s classic movie 8½ – with music and lyrics by Maury Yeston.

But he made his name as a shooting star in the off-Broadway theatre of the early 1960s alongside Edward Albee, Jack Gelber and the Living Theatre, placing his marker with the outrageous, surreal Freudian capriccio Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Bad (directed by Jerome Robbins and starring Hermione Gingold and the newcomer Sam Waterston).

Kopit originated the fad for long titles and, for good measure, added a subtitle, “a pseudo-classical tragi-farce in a bastard French tradition” that did not escape the notice of the critic Martin Esslin in his canonical history of the theatre of the absurd. Oh Dad was a jumble of historical and prophetic styles in its weird narrative of a grotesque mother arriving in a Caribbean hotel with her dysfunctional son and the coffined corpse of her husband.

The son strangles a girl – a babysitter in the hotel – who tries to seduce him, to the accompaniment of a chorus of bellboys, carnivorous plants and a talking cat. Esslin put it down to the fact that Kopit was a student at Harvard when he wrote the play that he could not match up to the more genuinely tragicomic effects of a Ionesco or an Adamov. But the play put him on the map, off-Broadway and beyond.

His two biggest plays thereafter were Indians – premiered at the Aldwych theatre in London by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1968 – a dream-like kaleidoscopic argument with the myth of the wild west shuffling between Buffalo Bill Cody’s travelling circus and the hearings of an Indian commission; and Wings (1978), a linguistic feat of reanimation in an immobile stroke victim who had once performed acrobatic stunts on biplanes, played by Constance Cummings.

Wings had first flown on American radio (with Mildred Dunnock) and visited the National Theatre for six weeks on the way to Broadway in John Madden’s sensitive, poetical production, with Cummings beautifully poised and vulnerable. It was revived at the Young Vic in 2017 with Juliet Stevenson giving a virtuoso performance as the stricken aviator Emily Stilson, swooping and diving in a harness which also gave her release.

Kopit’s Stilson was an amalgam of two women who had cared for his stepfather in a rehab centre after his stroke. His father was Henry Koenig, an advertising salesman in New York who divorced his mother, Maxine (nee Dubin), a millinery model, two years after he was born. Maxine then married George Kopit (pronounced Coe-pit), a jewellery sales executive, whose surname Arthur adopted.

After attending high school in Lawrence, Long Island, Arthur gained an engineering degree (1959) from Harvard, where he also wrote his first surreal plays and entered Oh Dad for a competition, which he won. The play ran for a year off-Broadway, toured for three months, opened in London (with Gingold), and played on Broadway for two. The critic Clive Barnes hailed Stacy Keach’s performance as Buffalo Bill as “a gentle triumph” and Kopit’s play “a multilinear epic”.

It was a so-so hit and remains an oddball favourite stationed somewhere between Eugene O’Neill, Irving Berlin’s Calamity Jane and Joe Orton. It also morphed into a cult movie in 1967 starring Rosalind Russell and Jonathan Winters (as the talking corpse).

There were several interesting efforts to keep Kopit on Broadway. He adapted Ibsen’s Ghosts for a production starring Liv Ullmann in 1983. And, in the same year, Hal Prince directed End of the World, his whimsical nuclear holocaust play – in which Linda Hunt was Tony-nominated as Kopit’s agent, the all-powerful Audrey Wood – to mixed reviews; some, including the Times’s Benedict Nightingale, thought it a spectacular success.

Nine was one of the great musical theatre events of the 1980s and earned Kopit his first – and only – serious money on Broadway. He was called in by Mario Fratti to revise the book: an ailing director – brilliantly played by Raúl Julia – struggles to make one more movie surrounded by his women – wife, mother, mistress, producer – in a sanitary white spa Venetian setting.

It really was Fellini’s 8½ plus a little bit extra. The fabulous show, directed by Tommy Tune, was revived less gloriously at the Donmar Warehouse in 1996 by the director David Levaux, who had more success with a Broadway revival in 2003 starring Antonio Banderas as the director, buttressed by Chita Rivera and Jane Krakowski. The movie starring Daniel Day-Lewis (2009) is not half bad, either.

Kopit’s critical champion, John Lahr, who thought – and still thinks – that Indians confronts the romance of the wild west with the reality of white colonial supremacy, and posits a brilliant argument with the Hollywood movie mythology – is adamant that it stands up as a bravura piece of theatre-making: “What the play trapped was the white man’s capacity for denial and for myth-making: the central ingredients to the American character writ large, even now with Trump et al.”

It may well be that Indians becomes an iconic American play about a nation confronting its own history (with metaphorical reference to the Vietnam war), alongside Tony Kushner’s fantastic Angels in America (also, like Indians, given its premiere in the UK, at the National Theatre) and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s sensational musical Hamilton. It certainly still bubbles under in college and am-dram performances on both sides of the Atlantic.

And Lahr reckons that Kopit’s greatest play remains unproduced: he worked for 25 years on Discovery of America, re-telling the fable of Cabeza de Vaca, the Spanish conquistador and the first European to set foot in the New World. At a time when colonialism in all its forms is up for critical grabs, you would not bet against Kopit making a major comeback from beyond the grave.

He is survived by his wife, the writer Leslie Garis, whom he married in 1968, their sons, Alex and Ben, their daughter, Kathleen, three grandchildren, and his sister, Susan.

• Arthur Lee Kopit, playwright, born 10 May 1937; died 2 April 2021