'Talking is all well and good, but it's time we did something about male mental health'

“We’ve all seen the usual kind of male mental health appeals hundreds of times by now,” Jack Rooke says, sighing. “It’s a shaven-headed hardman, or someone very laddish or a sportsman, sitting in the dark. He’s clearly unhappy but he can’t open up, so he just struggles on in silence. And then comes the message: ‘men, you have to talk'.”

He pauses. “Now, that’s all well and good. We should be encouraging men to talk, but the message just isn’t enough anymore, and we’ve been saying it for a long time. The question now is: what do we do next?”

A comedian, writer and campaigner, Rooke is starting what he calls “the next level” of the male mental health conversation. Progress has been good, he says, but the emphasis now needs to shift.

“The last few years have been brilliant for breaking down stigma, from Stephen Fry right at the start to all the celebrities recently who admit to having their struggles. But if we keep on simplifying it and not giving men options in who to talk to and what to do, we’re in danger of missing a chance to make a real difference. We could get stuck.”

Rooke knows the complexities of the topic. Now 27, he has spent the better part of five years working in various roles for the charity CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably), has suffered from mental health problems himself, and he’s explored the topic in his comedy work – most recently in a series of short BBC3 documentaries.

As a student in London in 2013, Rooke was still grieving from the loss of his father two years earlier, and began volunteering with CALM. At the time, the topic of male mental health was rarely spoken about and the then-new charity existed in a “tiny office smelling of feet in Waterloo.”

“Every few months they would move to somewhere much bigger, and that was a sign that things were changing,” Rooke says. “It just grew and grew and grew until people were becoming aware of the challenges we faced.”

The challenge in question didn’t just relate to the scale of mental health issues in the UK – that one in six people will experience a problem every week – or what little support there was, but also to the specific fact that suicide was, and remains, the single biggest killer of young men in Britain.

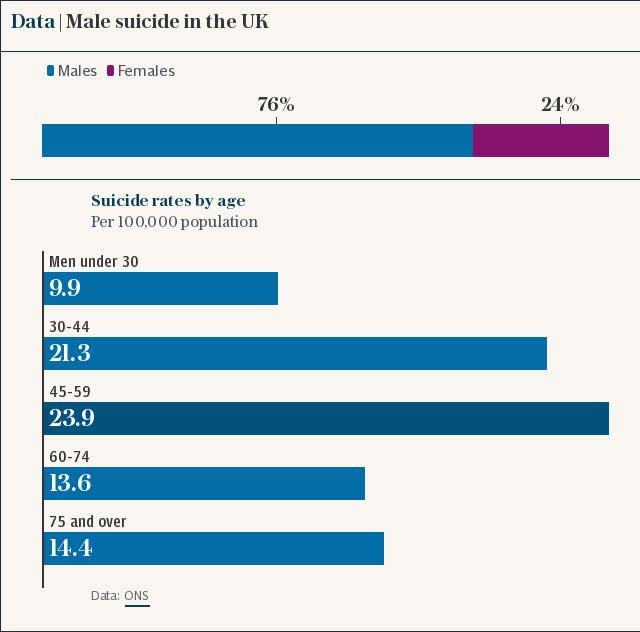

In 2015, 75% of all UK suicide victims were male. And in March of that year, Rooke’s old university friend, Ollie, became one of them.

“He was a close mate who had always struggled with his mental health, and quite openly too. When I heard the news I remember feeling devastated but also just angry – angry he’d been let down and this had been allowed to happen.”

When he recognised he was suffering from depression, Ollie had done everything right: he opened up, he turned to his friends, he went on medication and he sought counselling.

“There’s a ladder analogy I like to use, about what it means to be a successful man,” Rooke says. “The rungs on the ladder are a job, a house, a wife, a family, and if you feel like you aren’t climbing that ladder then the feeling of failure can be overwhelming. Ollie felt like he was moving backwards at the time, I think. He’d had to leave London and move back home, and couldn’t do what he wanted.”

Ollie’s death provoked Rooke to question the direction male mental health campaigning and treatment was going in.

“I realised that everything was getting over-generalised. In the media it was all emotion porn, and this thing about talking, but that’s what Ollie had done. I spoke to him about it frequently.

"Masculinity is far more complex than is being portrayed. Ultimately, he and so many others prove that we can’t just talk about it, we’ve got to do something about it too.”

Rooke, who has suffered from several bouts of depression, decided to explore what other options there are for men in his recent BBC3 documentaries. They included cold water swimming with a depression sufferer in rural Scotland, where mental health provisions are scant at best; going for runs; visiting an Afro-Caribbean barbershop; and even posing as a life drawing model to help build his body confidence. The idea was to look at alternatives to talking.

“We couldn’t get political on the programme, but it isn’t one party that’s been failing us on mental health anyway, so I wanted to see how people cope,” he says. “Some men just aren’t massive talkers, full stop. We should all open up and not leave things covered, but if there’s something you can do alongside that to make yourself feel better, do it. I do it in my live shows as well: ask people what makes them feel good. It doesn’t have to be regular or much, but it’s still really valid and important.”

Later today, Rooke will give a talk at the Being A Man Festival in London entitled ‘More Than Talking’, and that’s precisely what his campaigning is focusing on – both for men to keep moving forward after they’ve summoned the courage to open up, and for men who aren’t good at articulating their feelings to have alternatives.

“What I want is for men of all kinds to feel like they aren’t at a loss. The conversation so far has been good, but it’s too narrow and has barely changed since it started. It’s time we move on again and say: ‘right, what now?’”