Andy Warhol: Why the great Pop artist thought ‘Trump is sort of cheap’

During last year’s Super Bowl, 100 million US viewers were treated to a most unexpected sight in one of the commercial breaks. It was Andy Warhol doing nothing more than taking bites out of a Burger King Whopper – and adding the occasional bit of ketchup – for 45 seconds.

There was no music, no punchline, just a little, light rustling of the burger’s wrapper – in a slowly unfolding scene that culminated with the hashtag #EatLikeAndy. It was about as far removed as one could imagine from the big-budget ads traditionally shown during the Super Bowl.

Reaction on social media was swift, widespread and mostly containing the word “bizarre”. Why show a low-action clip from 1982, of an artist who died in 1987, at a sporting showcase in 2019? What financial sense did it make also – given that advertising slots at the Super Bowl are the most expensive in the world, costing $175,000 a second?

The answer is that the footage showed a great American artist eating a great American food in the context of a great American occasion. Burger King said the advert was a celebration of the country itself.

“If that clip proves anything, it’s that Andy is still very much with us,” says Gregor Muir, curator of a major Warhol show that opens at Tate Modern this month. “He’s a timeless figure, and our aim with the exhibition is to show that.”

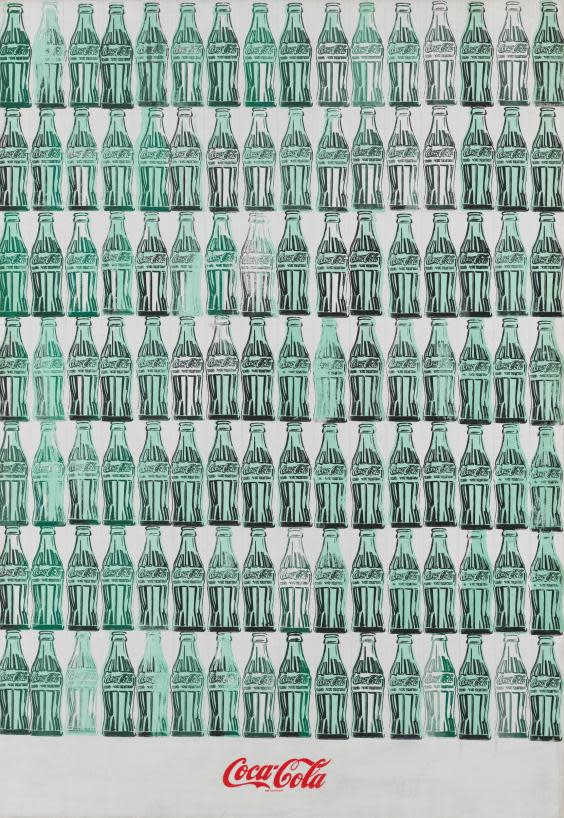

After a decade working as a commercial illustrator on Madison Avenue, Warhol began his artistic career at the turn of the 1960s. He sprung to fame as a leader of the Pop Art movement, which rejected high-cultural tradition and depicted everyday subject matter instead: in Warhol’s case, Coke bottles, Brillo boxes and Campbell’s Soup cans.

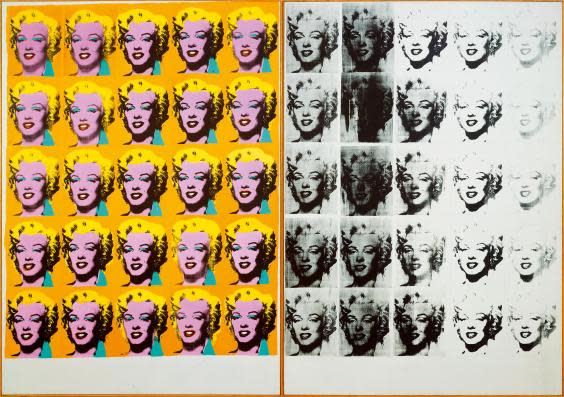

Soon he was silk-screening images of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley too. It suggested an artist entirely at one with America’s average Joe. The irony is, of course, that under the current president’s administration, Warhol’s parents probably wouldn’t have been allowed into the United States in the first place. Andrej and Julia Warhola hailed from a tiny village called Mikova on the edge of the Carpathian Mountains, in what today is Slovakia (but in their day was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire). In search of a better life, they moved to Pittsburgh after the First World War, where Andrej worked in construction and where Andy – Andrew Warhola – was born in 1928.

At the start of his career, Andy chose to anglicise his surname, by dropping the “a” at the end. Whenever asked about his ethnic roots, he declared, “I always feel American: 100 per cent.” (Interestingly, Warhol and Donald Trump did actually cross paths – at a New York party in 1981. The latter commissioned the former to create a silkscreen portrait of Trump Tower but turned the finished work down, and refused to pay a cent, when he didn’t like the colour scheme. “I think Trump’s sort of cheap,” wrote Warhol in his diary.)

The Tate exhibition sets out to show how large an influence Warhol has had on artists after him, especially in the way he embraced different media and means of distribution. In the mid-1960s, after the early burst of Pop works, he took to making films, such as Sleep, in which his friend, the poet John Giorno, can be seen sleeping for five hours.

He also founded Interview, a magazine in which celebrities from Cher to Michael Jackson were interviewed – and which ran for 50 years before its demise in 2018. And let’s not forget Exploding Plastic Inevitable, a multi-sensory stage show he conceived for the Velvet Underground, a band he briefly managed.

In short, he believed an artist could, and should, do more than just hold a paintbrush. An interdisciplinary approach to art is today taken as standard – and that’s in no small part thanks to the example set by Warhol’s adventures decades ago.

His influence extends far beyond the art world, though. “Warhol both predates and predicts the society we live in,” says Muir. On show at Tate Modern will be 25 paintings from a little-known series of paintings from 1975 called Ladies and Gentlemen. It depicts drag queens and trans women who frequented the Gilded Grape bar, off Times Square – and, in Muir’s view, “could easily pass for having been made yesterday, in terms of the debates being had now around trans identity and LGBT rights”.

Though dead for 33 years, Warhol anticipated the advent of social media. Take his Screen Tests, for example, 472 short films in which visitors to his studio were placed on a chair in front of a video camera and asked to “perform” solo for three minutes to camera – very much like the YouTube vloggers of today.

Then there’s his 1975 book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, usually described as a disjointed autobiography but better understood as a proto-Twitter account, given its author’s propensity for including both the most mundane of details (such as his love of jam on toast) and witty one-liners (such as “buying is more American than thinking”).

He also carried a compact Minox camera with him wherever he went, taking more than 100,000 photographs of friends, food, building facades, shop signs and the like – anticipating the Instagram feeds of our image-saturated age today. “I never read,” Warhol once said. “I just look at pictures.” (In his recently published autobiography, Me, Elton John tells the hilarious story of a time he and John Lennon had been taking piles of cocaine in a New York hotel room late into the night, when Warhol knocked at the door. As Elton went to answer, Lennon implored, “Don’t let him in: he’ll have his f***ing camera.”)

These individual episodes in Warhol’s career show his innate grasp of communications technology; the speed at which it was changing; and the direction in which it was heading.

He was aware of the inexorable rise of television, particularly with the proliferation of cable channels such as CNN, ESPN, Nickelodeon and MTV in the late-1970s and early-1980s. Warhol declared at the time that television “was the medium [he’d] most now like to shine in”, and he actually presented five episodes of an MTV talk show called Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes – a job cut short by his death, aged 58, from complications after a gall bladder operation. The show’s title referred to his most famous quote: “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.”

With these words, Warhol predicted the coming both of reality TV stars and social media influencers – as the platforms to achieve quick-fire celebrity grew exponentially.

“It’s often said Warhol was the most important artist of the second half of the 20th century,” Muir says. “But one might well argue he’s the most important artist of the early 21st century too.” In a consumerist society, he realised that celebrities are every bit as ubiquitous and disposable as soup cans, Coke bottles and Burger King Whoppers.

‘Andy Warhol’ is at Tate Modern, London SE1, from 12 March to 6 September; tate.org.uk

Read more

Does new Barbican exhibition have important things to say about men?