Andreas Gursky, Hayward Gallery, London, review: Great and fascinating detail

The Hayward Gallery has re-opened after two years of closure for a refurbishment. Has much changed? Surprisingly little. Except on the top floor, which now has those conical skylights in place that Henry Moore recommended be put in at the beginning. Which was when exactly? 1964, the year that the Beatles wowed the world on the Ed Sullivan Show.

The outcome was a bit of a fudge then. Now they are in at last, and we have the beneficence of natural light streaming down – which is a welcome addition. Otherwise, the downstairs spaces are still unpredictable in their sense of sideways (and then up, back, down, along, and then up again) driftingness. The too-narrow spiral staircase, which carries you up yonder, with its ribbed concrete walls, still feels mildly disconcerting, if not menacing. Where will it all end?

This career-long retrospective of the work of the Leipzig-born photographer Andreas Gursky is loosely chronological, from the early 1980s and on, but it is not at all easy to know in which direction to walk in order to to find that chronological sequencing. Does this matter much? Not really because Gursky often returns to his earlier preoccupations in his later years.

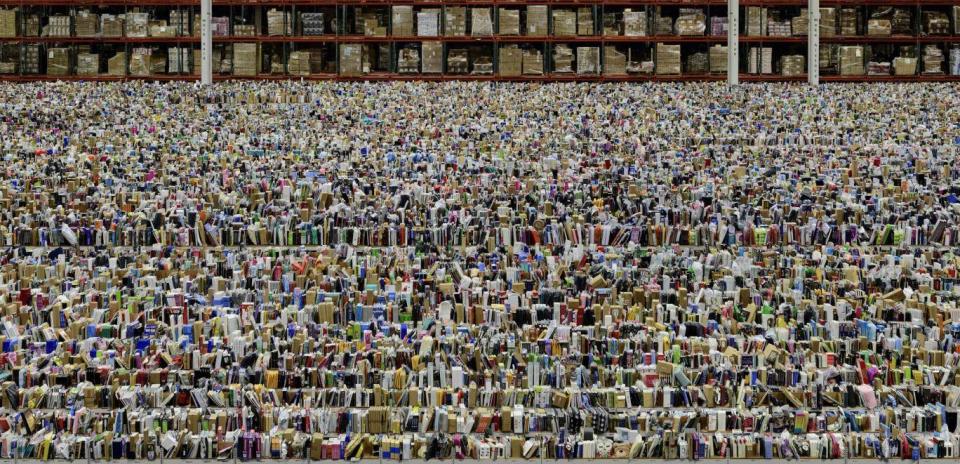

Most of Gursky's photographs are very, very large, even monumentally so, you might say, and these white walls, which rise to double height when you descend half a flight up from the ground floor, accommodate them well. They are also very tricksy in their representation of the world. In fact, these are not so much observed as made worlds. Gursky takes in huge quantities of minutely seeable content, often from a great height, at a stroke – which reduces it already to a form of abstraction - but that content is never seen as the human eye would see it. Take his extraordinarily wide and deep vista of the port city of Salerno, for example.

What astonishes is how everything seems to be in focus, and how so much - foreground, middle ground, and back – is seeable in such great and fascinating detail – from the rows of new cars, to the ships' containers at the port side, from the apartment blocks to the dizzyingly distant mountainscape beyond. Gursky creates his extraordinary, fabricated scenes by splicing together, with seamless cunning, multiple images, often taken at slightly different angles. It is for this reason that we can see every single writhing body at a rave in Dortmund. We seem to stand above the Tokyo Stock Exchange as swarms of human forms make their rhythmical, black and white patternings. Sometimes he adds and adds in order to create a great and near warring congestion of human excitability – look with care at the magical recreation, on the top floor, of a Formula One pit stop, at how dozens of mechanics seem to be swarming around the two stalled cars of the competing drivers, almost engulfing them, and how hundreds of observers seem to be photographing them from above. Far too many. The world is too much with us. But it feels exactly right – on the pulses.

January 25 to April 22 (southbankcentre.co.uk)