America’s mob violence and the politics of crude oil weigh on this Julius Caesar

There’s a lot of running in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s new toga-free production of Julius Caesar. It starts when Matthew Bulgo’s Casca runs in very fast circles around the stage – I assume to represent the chaos of a power vacuum in the aftermath of Caesar’s assassination. But it’s just one of director Atri Banerjee’s many staging choices that leave you scratching your head.

Then there’s the oddly avuncular presence of Nigel Barrett’s Julius Caesar, undermining the idea that this is a leader who cut a bloody swathe through Europe to cross the Rubicon in triumph. Barrett appears much older than his majority young cast, many of whom are performing at the RSC for the first time. Does he represent the declining old guard?

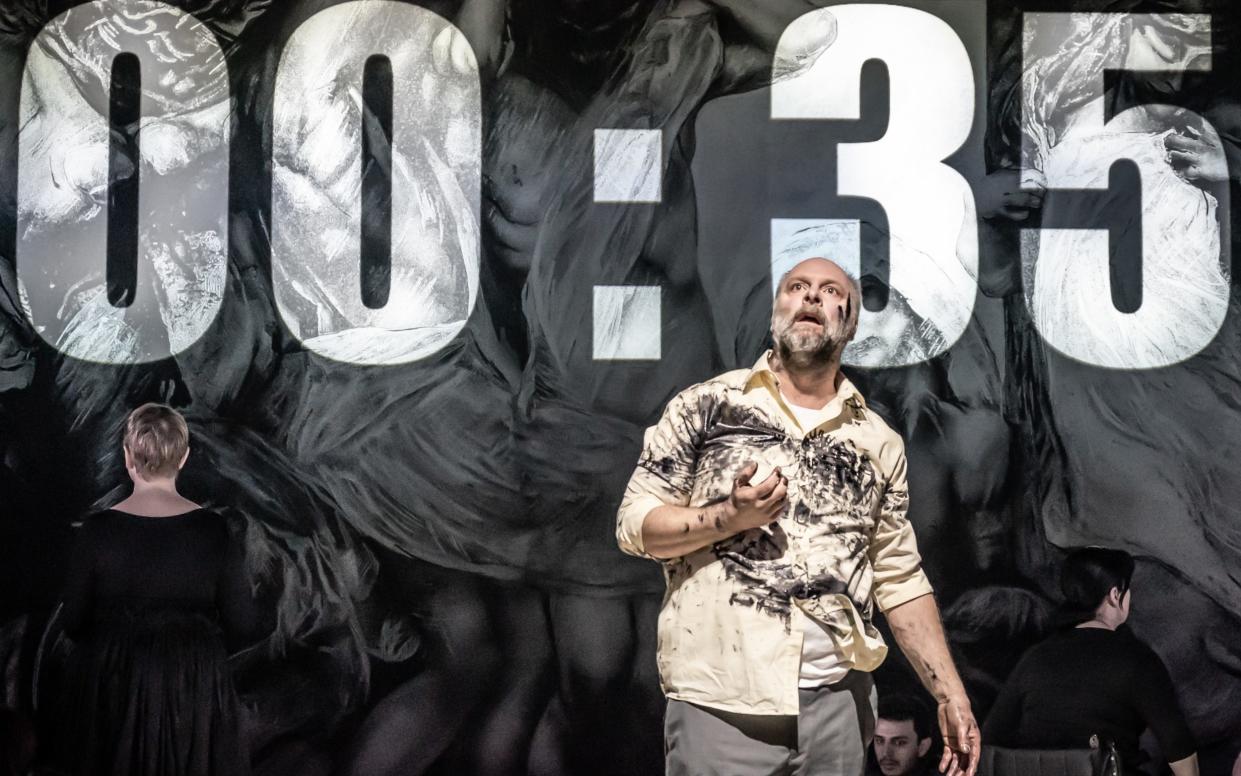

And why does the blood – which covers the cast until the end of the play – resemble a kind of black tar? Is it a statement about the politics of crude oil, or our complicity in hoisting to power those who wish to injure democracy and foster mob violence? Set in the non-specific present, there are parallels here with the violent insurrection at the US Capitol on January 6 2022, which left five people dead.

Rosanna Vize’s stage design is impressive: a revolving monolithic black cube onto which are projected greyscale images of swarming birds, time-lapsed decaying flowers, portentous skies and billowing smoke. While Lee Curran’s lighting, deliberately leaching colour from everything until Caesar and the dead appear on stage as colourful apparitions after the interval, is particularly effective.

But any salient points Banerjee is trying to make about the nature of power, friendship, fate and politics being far from black and white lose coherence beneath the melodrama.

The one thing that really holds this production together is the clarity with which the actors handle Shakespeare. I suspect that it's Banerjee’s attempt to tease out the granular complexities couched in the language that accounts for some of his curious choices of staging.

The chemistry between Thalissa Teixeira and Kelly Gough as, respectively, the gender-swapped Brutus and Cassius, also brings a new understanding to their characters and their motivations. Lines such as “ay me, how weak a thing / The heart of woman is!” and “she is an honourable man” with its altered pronoun become deliciously subversive.

Banerjee’s staging obviously owes a big debt to the theatrical imagery of director Ivo van Hove but it will be a while yet before he can wield this influence with assurance.

Until April 8. Tickets