Alexander Hamilton’s family enslaved people – so where should we stand on Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit musical?

In May 2018, with a slight grin on his face, an American news reporter asked three black members of the West End cast of Hamilton what it was like being in a musical about the winners “in the home of the losers”. They stared back, confused at the question and how it related to them. It clearly wasn’t the gotcha moment the reporter was hoping for. Many black people in the UK – myself included – who are first, second or third-generation immigrants don’t lose sleep over Britain not winning the American War of Independence, the story around which the 11 Tony Award-winning musical revolves. In fact, many of our families hail from countries colonised and torn apart by British rule and aren’t exactly filled with unbridled patriotism when it comes to Britain’s colonial legacy. Context is everything.

When Hamilton arrived on the new streaming service Disney+ on 4 July (to coincide with Independence Day in the US), it gave fans the opportunity to watch the hit musical at a fraction of the cost. But its small-screen debut also reignited a conversation on whether art has a responsibility to be historically accurate. Alexander Hamilton campaigned for manumission – slave-owners voluntarily freeing their slaves – but he was not an abolitionist. What’s more, his wife’s family – and that of Washington, another hero in Miranda’s tale – owned enslaved people. Hamilton even helped his sister-in-law Angelica with the “purchase” of an enslaved mother and child. As #CancelHamilton began trending on Twitter, a question arose: is it downright dangerous to oversimplify the history of the 10-dollar Founding Father, or just a flexing of creative licence – a song and dance not to be taken that seriously?

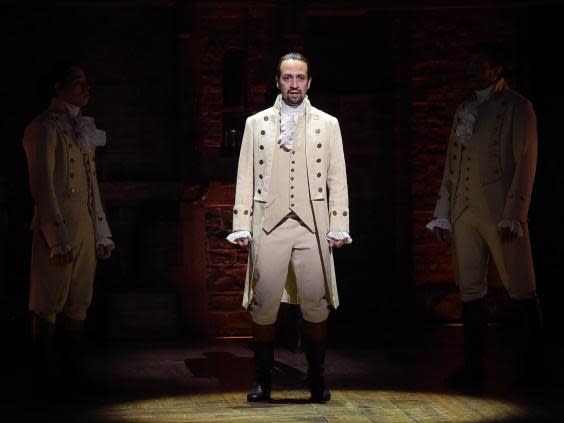

On the surface, it’s easy to see the intention behind a hip-hop musical about one of the lesser-known Founding Fathers. Hamilton premiered on Broadway in 2015 when Barack Obama was president; a young, bright-eyed Lin-Manuel Miranda (the musical’s creator and star) even performed one of the earliest versions of Hamilton at a poetry jam at the White House in 2009. If there was anybody who knew about working harder and being a self-starter, it was the first black president of the United States, the son of a Kenyan immigrant. Possibilities felt endless then. If a black man could be in such a position, then why couldn’t there be a play about the story of America with people of colour cast as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and George Washington? Wasn’t this proof that America was a land of revolutionary immigrants, and now the most marginalised descendants were loudly staking claim to the story of modern America’s origin?

Hamilton springboarded the careers of many of the actors in the original cast – Daveed Diggs and Leslie Odom Jr among them – and made jobs for a whole host of new creatives. And it undoubtedly spoke to a generation of people who felt ostracised by the white world of theatre.

Yet since its birth, the musical has been criticised for its historical inaccuracies, with most of the condemnation aimed at the gaping holes in Miranda’s re-telling.

For indigenous Americans and descendants of enslaved people, these Founding Fathers were anything but heroes. This generous retelling of history may seem like just epic fan fiction, but what about the oppressed and enslaved voices left out of the story? As statues topple across the globe, can we simply chuck aside the bad parts of history to praise the good? Poet and novelist Ishmael Reed despised the musical so much that he wrote his own play, The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda, backed by the late great author Toni Morrison, to address its shortcomings.

The world was a different place when Hamilton first emerged. It’s now 2020. Donald Trump – a man who wanted to build a wall to keep immigrants out – is president; in the UK, we’ve witnessed the Windrush scandal, where families of those who helped build Britain were ripped apart and some sent to their deaths for being immigrants; we are in the midst of another civil rights movement, where police brutality is being fought against during a pandemic that is disproportionately killing black people and people of colour. This all informs how Hamilton is perceived.

The musical’s changing context is not lost on Miranda, who recently tweeted, “All the criticisms are valid” and admitted that Hamilton “feels like it changed because the world around us changes so fast”. Lines like “immigrants, we get the job done” seem to fall flat in Trump’s America. And it seems insensitive to use racebending to make black actors play slave owners. This isn’t the same as Noma Dumezweni taking on the role of Hermione in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, where race isn’t focal to the witch in the fictional wizarding world. The story of America is everything to do with race, genocide and slavery.

In 2018, a musical about the suffragettes arrived at London’s Old Vic. It had a high-energy hip-hop score, centring on the Pankhursts with a majority black cast, including Beverly Knight. The Hamilton comparisons were drawn immediately. Even with its hiccups, I loved it – the musical loudly proclaimed that this fight for equality was for us all now. It felt strangely satisfying to watch black British women, who would have been left out of the suffrage movement, now taking centre stage. This idea of reimagining an inclusive history has an allure, but can it come at the cost of the truth?

I saw Hamilton last year knowing the criticism. I didn’t see it because I had an urge to learn more about the history of America through a musical while perched in the nosebleed seats. I went because I loved the songs and I wanted to know what all the fuss was about. I enjoy seeing black and PoC actors taking up space in a very white industry (even though visibility isn’t enough). Fundamentally, I do think it’s a good work of art. But again, context is key. This isn’t my history. How I view Hamilton as a black British person of Caribbean descent, who learnt very little of American history in school, will be different from an African-American person’s perception, or that of a white American.

Hamilton is out in the world; it exists and can’t be changed, regardless of any calls for its cancellation. But what can exist is a critical analysis of the musical, and a yearning to go and learn the facts, and not stop the education process at a fun musical. In the words of director Ava DuVernay: “That’s why I don’t look to art for my history. I study history.”